Tyler Robert Sheldon talks with Carlson-Wee about his forthcoming collection, dumpster diving, and poetic craft.

Tyler Robert Sheldon: Hi, Anders! It’s so good to talk with you again. Congratulations on your new book, Disease of Kings! Let’s jump into it. Kings seems to focus in part on the anxieties of the everyday, but also on the subverted mundane. In “Hired,” the opening poem, the narrator is paid to stand in place, an activity they were already doing…and in “Cora” and “Moving Sale,” the narrator and their friend North throw moving sales, though they’re not actually moving. How do these characters interpret their world? How should readers?

Anders Carlson-Wee: The narrator and his friend North have gone very far down their own peculiar rabbit hole. They pay for nothing, harvest all their food and clothing from dumpsters, sell what they can’t use, scam businesses on return policies, and are aggressively unemployed. The narrator sees life as a lucky chance to have a limited amount of time in this world, and he’s hellbent on keeping all his time to himself—hence, no work. This desire to avoid work and relish free time has led him to conclude that what he needs is to not need money. Yet his lifestyle also causes him great shame and humiliation, which he survives thanks to the company in his friend North. North is his lodestar, a companion that guards him from despair. As for interpretation, I’d say this: go down the rabbit hole. Let Disease of Kings immerse you in a strange new world—a hyper-specific world—and experience it on its own terms.

TRS: Resourcefulness is a key impulse in Kings. The early poem “Footprint” shows how many ways the world can be repurposed: “Bent nails / straighten. Warped wood warps // back.” Resourcefulness also seems to influence character decisions (as in “Snow”). As another example, you’ve talked in the past about dumper diving and living off the grid. Could you discuss how all of this impacted the book?

ACW: When I turned 18 and left home, I knew I wanted to have a life in the arts. I was willing to do almost anything to make that happen. After brooding on how to make my dream my reality, I concluded I needed to become extremely scrappy. So I began a long process of learning how to live without money. First, I spent time at wilderness survival schools, and, somewhat ironically, the transient kids at those school taught me urban survival techniques: how to dumpster dive for food and clothing, how to hop freight trains cross-country, how to ship mail for free. After that, I spent my twenties reading and writing as much as I could, living on a budget of $3,000 per year. I worked as a personal trainer, a job I obtained through a clerical error. I bought no clothes, no shoes, no food. Didn’t eat in restaurants, never attended anything that had a sticker price. That lifestyle was tough, and profoundly limiting, but it gave me what I wanted: an abundance of free time. It’s no overstatement to say that living that lifestyle bought me the ten years it took to become a poet. So while Disease of Kings is about that lifestyle, it also exists solely because of that lifestyle.

TRS: Some of these activities and experiences speak to the “hyper-specific world” you just mentioned. Shipping mail for free seems like it would help your work as a poet.

ACW: I’ll never tell…

TRS: Food frequently has a role in these poems. Sometimes it’s connected to emotions, like in “Call and Response.” How do you see it operating in your work?

ACW: Food is very important to me. As a dumpster diver, I’m acutely aware of the gargantuan food-waste problem in our culture—a problem so large that I’ve been able to thrive for years on a mere fraction of what’s thrown out at just a handful of supermarkets. To be clear: I don’t dumpster dive for a few crusts of pizza and half-eaten burgers; I dive for fifty filets of wild-caught Alaskan king salmon, fifty pounds of organic butter, fifty jars of expeller-pressed extra virgin olive oil, fifty bars of organic dark chocolate made with Madagascar vanilla. While Disease of Kings is spare—even bleak, in many ways—my characters indulge in a veritable jubilee when it comes to food. Food functions as a manifestation of faith: in their world, there is always some unexpected deliciousness hidden in the darkest, dankest corner, waiting to be saved and celebrated.

TRS: I’m reminded of your great chapbook Dynamite at times when reading through Kings, particularly in terms of how you depict violence. In Dynamite, it seemed like violence was immediate and bodily, but in Kings we see the violence that’s already been wrought upon the characters’ lives and setting. For example, in “I Feel Sorry For Aliens” you write of people and the world they’ve made: “How slapdash. How make-do.” Tell us more: how do you see the world as being influenced in this way?

ACW: I don’t consciously write about violence. I write from impulse, from my subconscious—and it seems there’s a good deal of violence lurking there. As for the different flavor of violence’s depiction between Dynamite and Disease of Kings, yes, in Kings the violence is more chronic and brooding and suppressed—we’re not at the moment of violence, as we were in Dynamite, but more in its aftermath, and awaiting its next advent.

TRS: A lot of poems here, as in a lot of your previous work, focus on the interplay of loss, risk, and opportunity. “Lou” and “B&B” come to mind, where characters teeter on the edge of great personal loss while also hanging onto hope for things to look up. How has this become such a compelling motif for your work so far?

ACW: I’m drawn to extremes of experience, moments of choice that come with great personal risk. These are the moments in life from which there is no going back. Not only are these moments profoundly compelling, from a narrative perspective, but to me, they’re also the moments we really need to study, to try to understand, and to practice. I believe one of art’s greatest gifts is the chance to practice such moments.

TRS: There’s a small thematic section in Kings that focuses on containers—a Subway cup, a shampoo bottle—and how they influence and help out our lives. Outside this book, in your and your brother Kai’s film Riding the Highline, we even see this focus applied to train cars. Does this notion crop up outside of the page/screen for you?

ACW: I love containers—and that goes for aesthetic choices as well. I’m a fan of imposed limitations. A good example of this is the dramatic monologue form, which I like to work in. When you’re writing a dramatic monologue, you have to convey everything through the speaker’s voice. If you want to convey the time of day, or what room they’re in, or what’s on the table in the corner, or who else is in that room with them, you have to find a way to do it through their voice. For me, the larger the limitation, the more generative I become. I think it’s the pressure of having scant options, an urgent sense of needing to work with what you’ve got.

TRS: I enjoy the moments in Kings that highlight characters’ voices and histories. “Barb” and “Oscar” are great examples of poems that use monologues to build setting and history. Are you always on the hunt for moments where a poem is “spoken into life” like this, or is it spontaneous?

ACW: While these pieces are written to feel spontaneous, they are not. Not really. For example, in order to arrive at the one dramatic monologue in Oscar’s voice, I drafted more than twenty monologues in his voice, covering all kinds of issues in his personal life as well as developing the nuances of his personality, manifested in his eccentric sense of humor. So, as the author, I know A LOT more about Oscar than I allow the reader to know. But all of that knowledge goes into creating that one monologue, and makes Oscar feel real (I hope).

TRS: Sort of expressing the essence of a particular character?

ACW: Yeah, their essence, their particular way of existing on this earth. You can express that across an entire novel, but you can also express it in a single poem, or a single photograph, if you’re extremely careful about what you choose to share.

TRS: Dumpster diving makes an appearance once again, in “Trash.” How does the practice continue to influence your writing?

ACW: There is an inherent optimism in dumpster diving. You are heading out at night into the unknown, with no knowledge of what you might find, but you go with the stubborn belief that you will, in fact, find something. I’ve been dumpster diving for twenty years, and after all that time, my faith in trash has done nothing but grow. I’ve had a similar experience with writing: the more I write, the more I believe there will always be something more to write. This makes me feel less precious, less attached to one piece or another, one idea or another. I know there will always be more material, more exciting aesthetic decisions to explore.

TRS: I love that idea—that we leave behind artifacts for others (and our future selves!) to find, which help us along in life.

ACW: At its heart, that’s what art is: artifacts left behind that might be of use to others—that might communicate something meaningful and help people live, and make sense of, their lives. And like trash, lots of art is sort of thrown away and forgotten, but that same art can be rediscovered by a new generation that finds value in the work.

TRS: The poem “Gout” reveals that its namesake is the disease of kings, caused by “overindulgence, excessive amounts / of red meat.” The narrator and North spend the poem indulging in dubious treasures—a wheelchair ride, a boat, the site of a cardinal-laden tree, all during North’s bout with the severe arthritis. Do you see the characters as subverting normal ideas of prosperity and hardship?

ACW: Absolutely. North and the protagonist have built a hyper-specific worldview with a completely unique value system. But within that shared worldview, they hold significantly different attitudes. While the protagonist is compelled to hoard what they have and guard it like a dragon guarding its gold, North is compelled toward wild indulgence and expenditure, trusting there will always be more, more, more.

TRS: And “Blizzard” shows North improvising a solution to what the narrator feels is an impassable problem: being snowed in. How do you feel that North and the narrator complement each other throughout Kings?

ACW: North is brave and strong and emotionally expressive. He’s on a rollercoaster of life’s ups and downs. He suffers from gout, cares for (and pays for) his alcoholic father, heads off to Alaska for seasonal work, comes up with wild business ideas and just as quickly abandons them. Meanwhile, the protagonist is fearful, self-conscious, greedy, and conniving. He is coddled by a stable father who loans him money. And as life changes all around him, he is unwilling and unable to change. Yet his temperament has an endearing side: he wants nothing to be wasted. Just as he wants to salvage thrown-away food, he also wants to salvage his friendship to North. He doesn’t want life to be new; he wants the same things to recur. He is in love with what he has. In the end, each character follows their own impulse: North moves on; the protagonist remains yet is grateful for what he has.

TRS: In poems like “Food Stamps Interview,” the narrator describes his circumstances in half-truths and omissions in order to gain advantage—but this feels like a necessity in the narrator’s world, asymmetrical as that world seems. We’re getting outside the poems a bit here, but that seems like a behavior that more and more of America is adopting in our rougher, pandemic-era country. Could you speak to this idea a bit?

ACW: Well, I think we’re currently facing a lot of new threats to our sense of reality. AI technology is taking away thousands of jobs, and no doubt creating others, but even if there’s some rosy possibilities for the visionary, the whole thing is destabilizing and uncertain. We also have deepfakes, hacks, fears of conspiracies, a brooding sense that news and media lies and manipulates, etc. And we’re dealing with the dissonance between online personas and personal realities, behaviors toward fellow humans in virtual spaces that would never occur in person, and things like that. Around me, I’ve seen the current times breeding doubt and nihilism, but also some radical rethinking of values: what life is, what life is for, how life might be lived. Whenever I see people radically rethinking their worldviews, I am optimistic, because I think past worldviews, in general, leave much to be desired.

TRS: Along those same lines, “Living Alone” grapples with different types of solitude—personal, emotional. Do you feel that this might tap into a universal human theme?

ACW: Oh yes. Loneliness is a universal human reality. Doesn’t matter how many friends you have or how hard you work to patch the holes in your heart—to be alive is to experience profound loneliness. But I think the condition is particularly acute in America. It certainly has been a huge part of my own emotional life, which is why I’m drawn to write about it.

TRS: If you could collaborate with any poet past or present, who would they be? Have any poets in particular found their influential way into Kings?

ACW: I am grateful to the many poets who have influenced my work. In the case of Disease of Kings, I owe an especially large debt to Robert Frost. Frost’s fingerprints are all over these poems, particularly the dramatic monologues, the character portraits, and the poem “House Fear,” which nods to Frost’s “The Hill Wife,” Section II (which is subtitled “House Fear”). I have also been deeply influenced by Jack Gilbert. But if I could collaborate with one poet, it would be my best friend, Edgar Kunz.

TRS: What’s next for you, personally? And what do you think might come next in your writing?

ACW: I’m living in LA and rock climbing a lot. I’m also working on a collection of stories. Over the years, I’ve tried to draft lots of poems that failed because their narratives were too large and unwieldy for the form. At some point I realized, if I switched forms, these narratives could finally have a chance to shine. Keep an eye out!

TRS: Will do! And finally, I just want to say thanks so much for talking today—I’ll look forward to the next conversation! How can your readers get their own copies of Disease of Kings?

ACW: You can order Disease of Kings on my website: www.anderscarlsonwee.com, or pick it up anywhere books are sold.

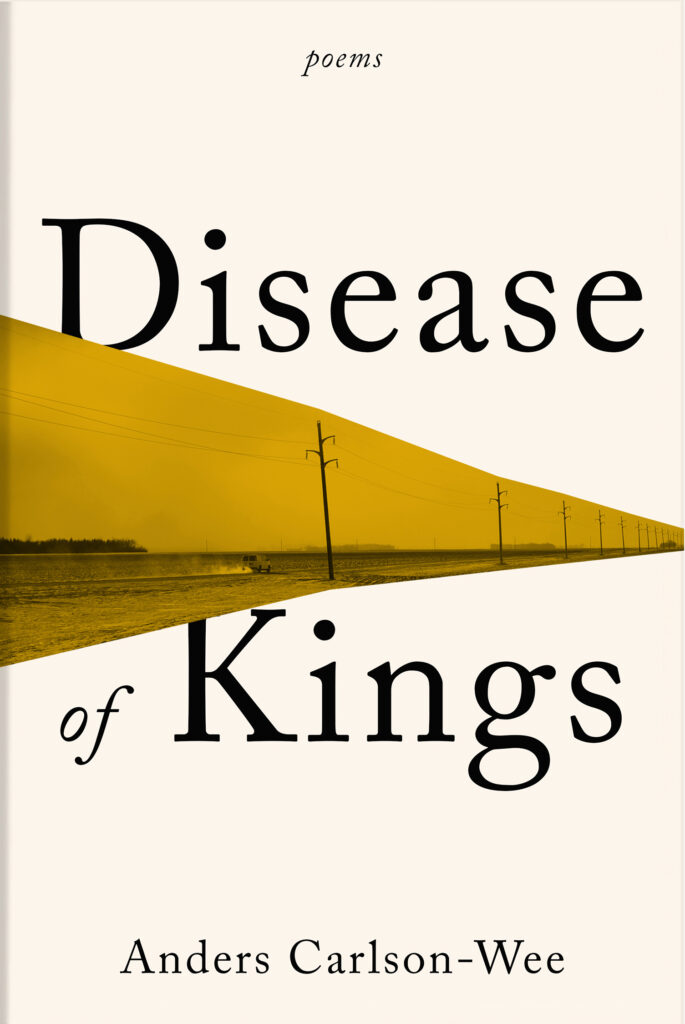

Anders Carlson-Wee is the author of Disease of Kings (W.W. Norton, October 2023), The Low Passions (W.W. Norton, 2019), a New York Public Library Book Group Selection, and Dynamite (Bull City Press, 2015), winner of the Frost Place Chapbook Prize. His work has appeared in The Paris Review, Harvard Review, American Poetry Review, BuzzFeed, Virginia Quarterly Review, and many other publications. The recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, Poets & Writers, the Camargo Foundation, Bread Loaf, Sewanee, and the Napa Valley Writers’ Conference, he is the winner of the Poetry International Prize. Anders holds an MFA from Vanderbilt University and is represented by Massie & McQuilkin Literary Agents.

Tyler Robert Sheldon is the author of six poetry collections including When to Ask for Rain (Spartan Press, 2021), a Birdy Poetry Prize Finalist. He is Editor-in-Chief of MockingHeart Review, and his work has appeared in Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Pop Culture and Pedagogy, The Los Angeles Review, Pleiades, SLANT, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, and other places. His research interests include poetry and poetics, comics studies, pedagogy, and World War II. He’s received numerous awards for his writing and pedagogy, including the Charles E. Walton Essay Award, the Dickens Project Essay Prize, and nominations for the Pushcart Prize and AWP Intro Journals Award. Sheldon earned his MFA at McNeese State University, and he lives in Baton Rouge, where he teaches, writes, and usually has a cat on his lap.