Fuori di Testa

A crush starts in the back of the throat, at the edge of a swallow, attraction meeting a hint of repulsion like a wave rolling forward even as it pulls back, like “uh-oh” and “here we go again,” again being the operative word. Crushes are iterative: with each new one, you’ve been here before, never mind that you’re forty, then fifty, then fifty-five years old and happily partnered; the crushes keep coming on people you know and people you don’t.

Now it’s Måneskin, the young, Italian glam rock band who won Eurovision in May 2021. Not that I knew about them at that point or had ever cared about a song contest that favors sentimental ballads. And not that glam rock appeals to me particularly. That’s the way with crushes: they often don’t make sense, or rather, they make a kind of dream sense, pointing toward something you don’t know you know.

Måneskin came into my life the old-fashioned way, through a song on the radio, as I drove my teen son home from school on a fall afternoon. We were talking about that evening’s basketball practice when, for maybe for the tenth time, “Beggin’” seeped into the background. The song felt old, as in 90s-British-indie-rock old, or 80s-Rolling-Stones-on-the-charts old, with an undercurrent even older than that, and at the same time, utterly new. The singer’s voice, erupting from that edge-of-pain place where crushes begin, pleaded for two short verses before launching rapid-fire rhymes impossible to understand, but that raspy, disembodied man understood something that provoked me. I asked my son to Google who was singing, and he said “some white guy,” and when we got home I spent an hour falling in love.

Not with Damiano David, mind you, and not because he was only twenty-two, the eldest of the group, but with Måneskin (pronounced MOAN-eh-skin), three guys and a woman with musical chops and attitude and style and story, and since that day I’ve been listening, watching, following, searching and finding, like a guilty pleasure except there’s no guilt. No apology. Just the anticipated thrill of responding to the first person who might suggest I have too much time on my hands (though I don’t) or a sex drive that isn’t winding down on schedule (though it isn’t) with the middle fingers of both hands.

A crush starts in the throat and moves down, through the digestive system and into the hips, the lower back, the place that stretches when you arch until a yawn spills forth. A place with direct connections to the limbic brain, where emotions and higher-order thinking meet. Or at least that’s how it happens now, in the stage of life when questions are often more compelling than answers, when I ask “Why?” and “What does this say about?” for the pleasure of possibility.

First, though, “Who?” Måneskin formed in 2015 after three middle school friends in Rome posted an ad on Facebook for a drummer and hired the only kid who replied. Soon they were busking on the Via del Corso and developing a flamboyant performance style to catch the attention and the euros of passersby. When they needed a band name, bassist Victoria De Angelis, who is half-Italian and half-Danish, began saying random words in her mother’s language, and måneskin (moonlight) stuck. In 2017 the band joined the Italian X Factor reality show, where they performed a rendition of “Beggin’,” the 1962 hit by Italian-American Frankie Valli, that brought the house down. Although the band came in second in that competition, they subsequently released an album, and in early spring 2021 won Italy’s Sanremo music festival with their original song “Zitti e Buoni” (“Shut Up and Behave”). That win guaranteed entrance into Eurovision where, against all advice, they performed the same hard-rocking song, an anthem to freedom of identity and expression.

Måneskin were already famous in Italy by that point and had something of a following elsewhere, but the day after the Eurovision finale, “Zitti e Buoni” hit number one on the song charts of twenty-five countries. That was in May. The band headed straight from their win to a villa in the Italian countryside, where they wrote and recorded a second album that did well throughout Europe over the summer. Then, seemingly out of the blue, the four-year-old cover song “Beggin’” went viral on TikTok and began climbing the worldwide charts, including in the U.S. Over the next year and a half, Måneskin performed on American hit TV (The Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon, Saturday Night Live, Dick Clark’s Rocking New Year’s Eve), opened for the Rolling Stones in Las Vegas, played Coachella and Lollapalooza. With each passing month, they attracted more fans, more accolades and, just before their third album release in January 2023, a Grammy nomination for “Best New Artist.”

Those adjectives apply as well to De Angelis, the bassist who describes her favorite clothing style as “tits out” and sometimes performs completely topless or topless under an open jacket or topless under an open blouse that hugs her shoulders and slips beneath her arms, tying behind her back. Because social media platforms tend to censor women’s nipples, she often places electrical tape in black X’s across hers, at once protesting and exercising savvy control over her image.

Thomas Raggi, the youngest band member and a shockingly accomplished guitarist by the time he turned twenty, dances with a Ukrainian folk kick and wears designer suits or vests and thick black eyeliner like all his bandmates, lids dusted purple or red. Ethan Torchio, perhaps the most beautiful of all, drums with long black hair flying, biceps strong from speed and force, in contrast to a lace blouse or Victorian corset. When the band started out he was fifteen, skinny, keeping time on a cajon behind his showier bandmates, a boy I would have given money to in a heartbeat to encourage his dreams.

Although the singer and guitarist describe themselves as straight, the bassist as bisexual, and the drummer as “sexually free,” Måneskin balk at the notion that their appearance is a strategy. Said De Angelis in one interview, “Some people accuse of us queerbaiting because we look and act the way we do. But that’s flawed thinking. We don’t believe that clothes are connected to a person’s sexuality. That the boys are wearing make-up does not tell you what gender they are attracted to. Those two things should never be equated with each other.” Neither should the way people express affection. At the end of concerts, the “boys” often kiss one another on the lips, sometimes to make a political point. In Poland, during an anti-LGBTQ legislation campaign, David and Raggio locked lips onstage. The crowd went wild, even moreso when David screamed, “We think that everyone should be allowed to do this without any fear! We think that everyone should be completely free to be whoever the fuck they want!” When I watch that clip, I feel the crush quite literally, in the center of my chest.

Maybe “crush” isn’t the right word, but what else is there? Admiration is too tame, infatuation too fleeting. A crush feels exhilarating and dangerous, thrilling precisely because it sneaks up and bites your earlobe, then motions for you to follow. You don’t have to, it says, but you’re pinned down and carried away at the same time, as if there isn’t a choice. Because there isn’t a choice beyond the age-old dilemma of whether to accept or reject pleasure, which for me is no dilemma at all.

And so the crush becomes an obsession, interrupting your days and nights with its seductive impulse. At work I search and scroll, piecing together the larger story, watching Måneskin transform from hippie-inflected teens into self-possessed young adults influenced by Bowie, Jagger, Led Zeppelin, Metallica, as well as Brittney Spears and Miley Cyrus. Tattoos appear, eyeliner, latex and leather. Bodies fill out, muscles form, skin becomes bare, so much skin. I can’t stay away, not from any one of them in particular but from the band as a whole. Watching the 2018 documentary “This is Måneskin,” I’m struck by how they nip and tease one another, draping limbs over limbs and, alternately, how serious as they work through new songs in the studio with concentration and joy. I don’t want to be them and I don’t want to be with them, but I want something that exists among them, some combination of humility before the craft, absolute confidence in hard work, and the fun of creation.

In interview after interview, De Angelis and David, the most fluent English speakers of the group, describe Måneskin’s mission: to make good music aligned with their commitment to rights and expression and experimentation. The single “I Wanna Be Your Slave” from their second album (a version of which they recorded with rock icon Iggy Pop) celebrates the longing to dominate and submit, to assert and confess and seek redemption. The music video intersperses performance of the song with footage of the band members in BDSM-inflected scenes. In one arresting clip, Torchio kneels before De Angelis, who bends forward to propel a heavy string of saliva onto his upturned cheek. When one interviewer asked what the band was trying to do with this video, David explained that they wanted to represent and normalize the range of sexual appetites. The interviewer pressed him: “So you’re sending out the message that if somebody thinks spitting is hot during sex, it’s hot? It’s not gross.” A smiling David replied, “That’s not gross. That’s not gross at all.” I’ve watched that clip a dozen times, captivated by the composure of the band, the way Raggio’s heavy eyelids never raise, Torchio nods, and De Angelis voices her agreement, and the only unseemly aspect of the whole thing is a band asked to talk about what is so patently obvious in their art.

In fact, I’ve watched hundreds of clips over and over. The concerts, the interviews, the fan footage of meeting Måneskin on the street. Every day I skim Instagram, enjoying photos or videos of band members posing seductively in bathroom mirrors or mugging together in the back of a car or resting between recording sessions or lounging at the beach on vacation. I track what country they’re in, what city, whose birthday it is and the kind of celebration they’re creating. My compulsion even expands beyond the immediate band to their friends, romantic partners, relatives. I have an insatiable desire to know, to imagine, to see how life happens in a circle far away from my life, and why is that? What is this call to spy into the lives of 20-somethings from Rome?

The obvious answer would be that their lives seem charmed, their success seductive, that a woman in a later stage of life would of course harken back to youth, drawing pleasure from vicariously re-entering adulthood. But that’s like saying ice cream appeals because of its temperature. On a hot day, sure, but what about the nuance of taste and texture, the sweet and salty and bitter, the occasional crunch that awakens and provokes?

“Ardor” might be the most useful term, with its Latin roots in burning heat, the kind that envelops, destroys, renews. Chaucer described ardor as “wicked,” John Milton as “noble,” and some combination feels right for what I’m trying to name. It starts with that heavy bass, sometimes joining the guitar to carry melody, with the cathartic anger and surprising tenderness of English lyrics or Italian rhymes that fit together like puzzles. It starts with that layered voice and, improbably, just three instruments. It feels ridiculous to be impressed by musicians who actually play their instruments, but I am and they do, exceptionally. (After Måneskin’s SNL appearance, music producer Mark Ronson tweeted, “Shocked by how wildly refreshing it was to hear a big full sound coming from three musicians, one singer and zero backing track on @nbcsnl last night.”)

Then there’s the personality of the band, audacious and grounded. David seducing the audience with a drag queen’s cheeky gestures. De Angelis stomping to the beat, then sinking to her knees with hips writhing as if making love to the rhythm. Raggi’s entire body moving constantly as he holds the guitar at waist level, knee level, above his head, or lying on his back on the floor, hips in the air, or sitting atop David’s shoulders or crowd-surfing without missing a note. Torchio kicking the bass drum, his body bouncing into the air until he stands and silences the cymbals with a grasp, then sits again, sticks moving so fast they nearly disappear. He’s often the last to leave the stage, throwing drumsticks to the crowd and blowing kisses. These are not 1970s rockers who get fucked up and trash hotel rooms. They’re playful, performative, reflective. When asked by an interviewer about the future of the band, David said they want to keep making music for as long as possible. And the secret to that? “Stay healthy,” he replied, laughing. Which immediately brought to my mind a joke about the climate crisis: We have GOT to start thinking seriously about the world we’ll leave Keith Richards.

Richards, of course, is famously hard-partying, while Måneskin favor moderation, but the Rolling Stones’ flirtation with glam rock might offer a clue to my attraction. When glam arose in the 1970s, in contrast to the aggressive masculinity of rock and roll, its performers were self-consciously androgynous, performing gender in a way that loosened it from biology. As Philip Auslander writes in Performing Glam Rock: Gender & Theatricality in Popular Music, “Glam provided very public images of alternative ways of imagining gender and sexuality,” the result of which was a “demand for the freedom to explore and construct one’s identity, in terms of gender, sexuality, or any other terms.”

That’s the ethos I came of age with, but we live in different times now. Måneskin’s retro embrace of glam rock feels refreshing, even amid contemporary artists who embrace androgyny (Lil NasX, Halsey, Harry Styles). When David performed a pole dance to the Struts’ “Kiss This” on Italian X-Factor, wearing stiletto boots and black X’s over his nipples, it felt not like a parody of a female stripper but like an expansion of what a man can do. When Raggi took the stage while opening for the Rolling Stones in Vegas, wearing a sequined, one-shouldered crop top, he looked chic. Not like he was making a point or trying too hard, just comfortable and cool and unapologetically thrilled to be there. The design palette for the band that night was red-and-white striped pants and navy tops with white stars, form-fitted and showing strategic skin, like walking, rocking, sexually free American flags. How, I wonder, did every one of those Rolling Stones fans not fall in love?

Quite a bit has been written about fans of musicians, from the Beatles to Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Frank Sinatra, even Franz Lizst, the Hungarian composer whose mid-nineteenth-century piano recitals aroused audience members to the point of fainting. But not much attention has been paid to women of a certain age (or men of any age) who experience the kind of compulsive attraction I feel for Måneskin. That’s a shame, because one thing I learned at Måneskin’s Chicago shows this past year is that their audience spans many decades. After their Lollapalooza set, a boy of about eight ran up to me and said of my “Zitti e Buoni” concert tee, “I love your shirt!” Ten minutes later, a sixty-five-year old man pointed to my shirt and raved about the band. He’d driven his daughter from Ohio to attend the festival, he told me, but partly because he’d wanted to see Måneskin. “I’m really too old for this,” he said, breaking into a smile when I disagreed.

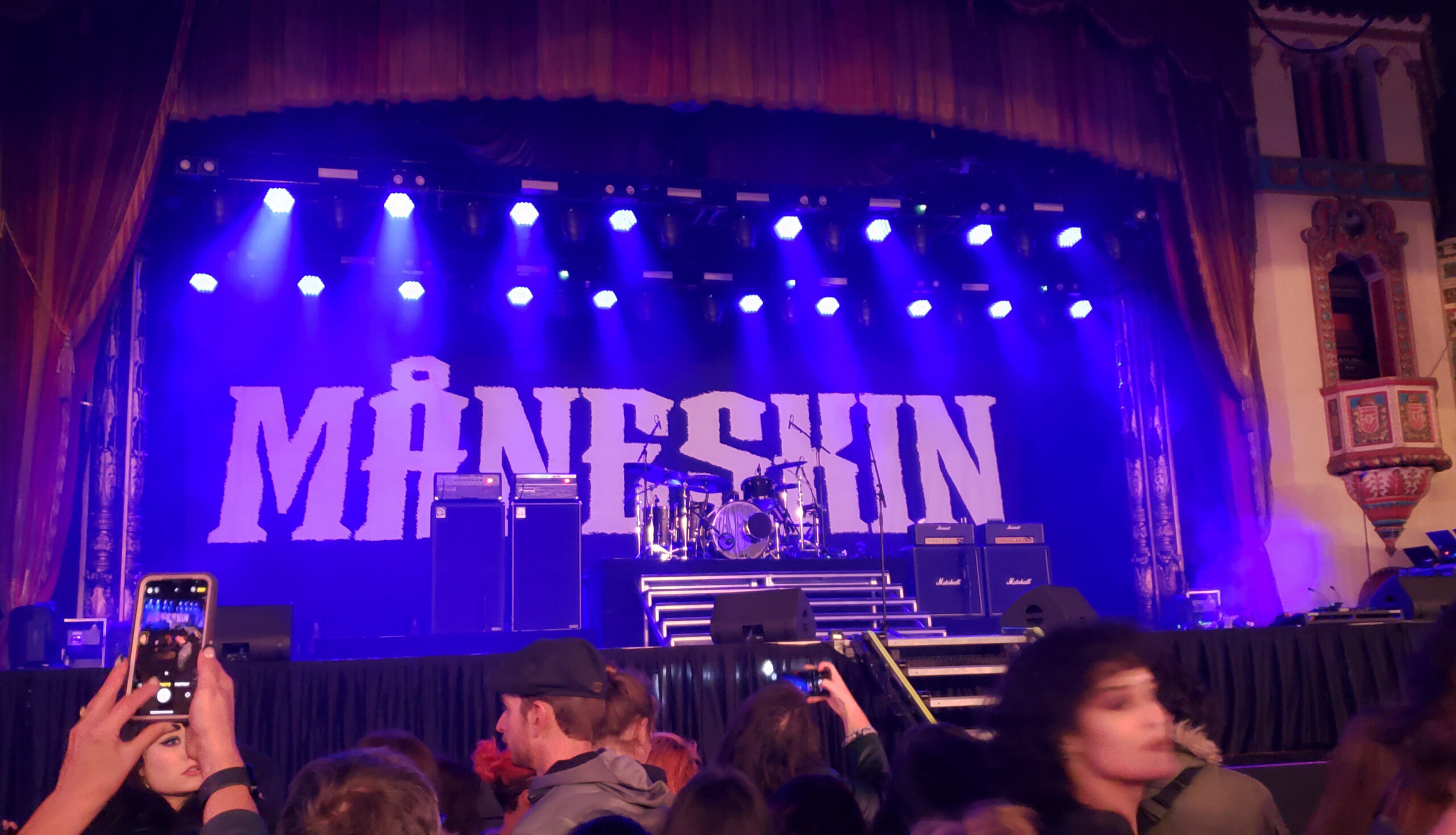

I go to shows alone, not because I prefer it that way but because I don’t have a single friend or relative willing to stand in line for hours with the General Admission crowd in order to squeeze close to the stage. And maybe it’s because I’m alone that people talk to me. Outside the Aragon Ballroom in November 2022, a fifty-two-year old woman told me her daughter, who was meeting her shortly, had gifted her tickets for her birthday. “I can’t help it, I love them,” she confessed, stomping her feet and hugging herself against the cold. Inside after the show, as the tight crowd shuffled toward the exit, the nurse beside me exclaimed, “They’re young enough to be my grandkids!” before describing how amused her college-aged children are by her fandom. When a voice behind us shouted, “Professor!”—the second time I’d run into a student that evening—the nurse opened her eyes wide and laughed.

Although the Måneskin fans I’ve personally met have been lovely, they aren’t always. In one interview, Damiano David said he was “trending with the MILF set” and described a meet-and-greet at which he signed a CD for a woman in her 50s who then grabbed his “package” in plain view of a large crowd. I have no way of relating to that, except by noting that sexual assault is everywhere and that whatever was going on with that woman is not even close to what is going on with me. But what, exactly, is going on with me?

In her essay, “My Coming Out as an A-ha Fan,” Eiken Bruhn describes rediscovering the Norwegian band she’d been in love with as a 1980s adolescent. To her happy surprise, A-ha had recorded albums in the intervening years, and now in her mid-40s Bruhn was as appreciative of their music as ever before and especially moved by a 2017 acoustic version of the hit “Take on Me.” Bruhn writes, “Magne Furuholmen, who is widely known as the keyboarder in the band and one of its two songwriters, is my hero because I attribute qualities to him that I would like to have: fearlessness and a presence in everything he does.” The notion that we crush on musicians whose qualities we envy (only later, if ever, understanding we’ve projected them) rings true to me. But with Måneskin, what I admire isn’t what I crave, including their youth. I actively would not want to return to early adulthood. And although watching them sometimes feels sexual, making me want to press skin to skin, absorb and externalize desire, it’s not their skin I crave.

Sometimes while watching footage of Måneskin, I think about my mother who came of age in the 1950s in small-town New York State. She married “late” at 24, had two children, and left my father for a woman at 39. I was twelve years old by then and devastated not so much by the split as by the secrecy surrounding our new life. “Unfit” was the adjective immediately applied to lesbian mothers then, and although mine was brave for withstanding that pressure for a time, it came at a cost. Just before a scheduled custody hearing, at which my father planned to argue that his children should not be subjected to homosexuality, my mother reconciled with him to avoid losing us. What a shame that she grew up in the time and place she did. How much happier she would have been with role models who believe in, insist on, enact the principle that love is love and sexuality happens along a spectrum. My mother knew that, of course, felt it in her bones, but she couldn’t claim or feel at peace with her identity. Even after she left my father a second time, her relationships with women remained secretive.

So I’m thrilled that Måneskin exist as role models for all sorts of young people who don’t fit the expectations of family and culture. It gives me breath-catching hope that lives will change because of this band, that their earnest insistence not on tolerance—that condescending hat-tip—but on celebration will help shake loose the notion that self-expression is threatening. I love Måneskin’s style and unapologetic confidence, and I especially love how essential their progressive, communal sensibility feels, even all these years after I thought we’d cleared that hurdle.

But all of this is conscious, and the most intriguing part of a crush is what ripples below the surface. During a stressful morning at work, before I even have a chance to take a deep breath, “Morirò da Re” (“I’ll Die Like a King”) begins playing in my mind, creating a sense of calm focus. When I wake in the middle of the night, a back-of-the-eyes sensation announcing that sleep has crept away for a good while, the ballad “Coraline”—over six minutes long and a global hit on Spotify—appears in the same way, soothing me away from watching the clock. Instead, I scroll through photos and silent performances on my phone until drowsiness returns, and this is not meditation but it’s not not meditation, either. It’s a distraction that gives traction, enabling the mind to climb up out of the muck and, from slightly higher ground, find a new perspective.

And what is that perspective? As Bruhn writes of her mature feelings for A-ha, “When more doors close or are already locked, the view shifts back from the outside to the inside. Who am I and for how much longer?” The first part of that question I have a decent handle on now, but the “how much longer” part makes me think hard. Not about the shortness of life; my crush on Måneskin isn’t about time running out. It’s about transformation. How long before the guiding questions of my life shift once more, before hard-won truths reveal themselves to have been a mirage? Crushes point toward the parts of us that need tending, that are on the verge of blooming or fading away or transitioning into something we can’t yet identify. Which is exciting. Ravishing, even. Generative.

That’s how it felt to stand not far from a stage one July afternoon, two days before Lollapalooza. Instagram had turned me on to this free, pop-up set, just half an hour long and sponsored by a Chicago radio station, and as the band took the stage, stepping from darkness into light, as the crowd surged close in a roar of appreciation and the opening notes of “Zitti e Buoni” thumped against my chest, something fell away. My arms shot up, head flew back, voice lifted with a passion I hadn’t seen coming. I jumped, punching the air, transcending my body in the nearest thing I can imagine to what lovers of roller coasters must feel at the apex. In a much larger crowd at Lolla two days later, I would glimpse this sensation again, but now, indoors and enveloped by the bass and electric guitar, the stomping, crashing drums, the intimacy of a small space and the energy of fans of all ages—from a little kid atop his father’s shoulders to leather-skinned rockers older than me—I felt the exhilaration of discovery, possibility, wonder, wanting. Like a humid summer morning when treasures might lie ahead: a make-shift haunted house in the neighbor kid’s basement, a pile of two-by-fours in the woods across the street, a new novel in the library offering access to another place, time, life. I felt the literal crush of the crowd and the metaphoric squeezing of a carapace splitting open. Later, I would watch videos, my own and others’ posted to fan accounts, and feel it again, a little less powerfully each time.

In “The Warmth of a Lost World,” an essay about visiting Turkish bath houses as the pandemic began, Leslie Jamieson writes, “There can be a radical honesty to pleasure, a profound nakedness in surrendering fully to unguarded, unselfconscious states of enjoyment. It’s harder to hide or dissimulate when you’re enjoying yourself.” Certainly that idea applies to my crush on Måneskin, its pleasure perplexing yet deeply, maybe even radically, honest.

Nearly two years into this obsession, I’m waiting for it to fade. When the new album came out in January, I approached cautiously, worried I might not like it and then what? But no. I love all but one of the songs and sing them day and night: “Own My Mind,” “Gossip,” “Timezone, “La Fine” (“The End”). I did balk when the band marked the album release by holding an elaborate mock-wedding—to one another—in Rome, but then the next day De Angelis posted, “Still not sure exactly what happened last night, but our new album RUSH! is finally out…” and all was well again. For months now, Instagram has offered snippets of the European tour—Amsterdam, Köln, Berlin, Paris, Bologna, Florence, Trieste, Milan—before Måneskin head to the U.S. next month, and I’m loving it all.

How much longer will this fixation last? Crushes are by nature temporary, circumstantial, tied to a changing internal landscape. At some point in the future, I’ll realize I haven’t checked social media in a while and the Måneskin tab on my music app will slip below other choices. Right now, though, I’m gearing up for a Chicago concert in late September. I’ve got my solo ticket and look forward to singing, dancing, punching the air and, alternately, throwing my middle fingers around, losing my mind as the “Zitti e Buoni” refrain says: Sono fuori di testa me diverso da loro (I’m out of my mind, I’m not like the others), defying not just logic but understanding, embracing the snippets of dreamlife that burst into our days.

The other afternoon, while shopping for putty knives in the hardware store, I heard a gorgeous balled, “The Loneliest,” playing in the background. My face flamed, heartbeat raced. “Måneskin,” I whispered to my partner, pointing toward the ceiling in the universal sign for “Listen.” To his credit, he didn’t roll his eyes or shake his head as though I were beyond understanding, even if that’s true. He just nodded with recognition, bearing witness to the inexplicable joy.

Michele Morano is the author of the essay collections Like Love (long-listed for the 2021 PEN-Diamonstien-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay) and Grammar Lessons: Translating a Life in Spain. She is currently working on Death Wishes, a book-length essay about the concept of a good death. She teaches creative writing at DePaul University in Chicago.