An Interview with Major Jackson

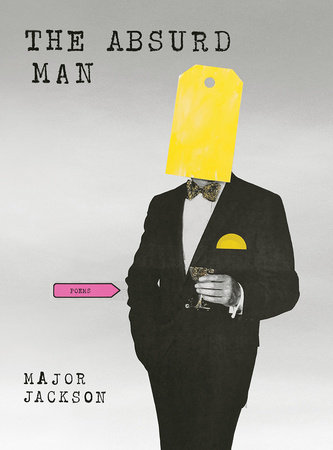

Major Jackson’s fifth book of poetry, The Absurd Man (W.W. Norton), was published in February 2020, at a time when an already tumultuous political and cultural climate was exploding with anxiety, fear, and outrage. Nationwide protests against police violence, a deadly outbreak of COVID-19 resulting in mass quarantines, and a widespread distrust in the U.S. federal administration sent the country into an unprecedented state of existential dispair. At a time when we are confronted with our own mortality, isolated from and often at odds with our friends, family and fellow citizens, The Absurd Man feels like an especially important and timely collection. In these poems, Jackson explores the complexities of relationships, both with the self and with others, and contemplates the way we position ourselves, or try to, in the universe. As he says in his interview with Ninth Letter staffer Liz Harms, “Meaning or the lack thereof, in the cosmic, existential sense, is the dilemma that drives much of the book.”

We are delighted to present the full interview with Jackson here, along with two brand new poems, “Wonderland Trail” and “The Ocean You Speak to,” both of which resonate with the fractured and uncertain state of the world we live in. A third new poem, “Eleutheria,” is featured in our recently published pandemic anthology, my heart. your soul.

In addition to The Absurd Man, Jackson’s other books include Roll Deep (2015), Holding Company (2010), Hoops (2006) and Leaving Saturn (2002), which won the Cave Canem Poetry Prize for a first book of poems. His edited volumes include: Best American Poetry 2019, Renga for Obama, and Library of America’s Countee Cullen: Collected Poems. A recipient of fellowships from the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Guggenheim Foundation, National Endowment for the Arts, and the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University, Jackson has been awarded a Pushcart Prize, a Whiting Writers’ Award, and has been honored by the Pew Fellowship in the Arts and the Witter Bynner Foundation in conjunction with the Library of Congress. He has published poems and essays in American Poetry Review, Callaloo, The New Yorker, The New York Times Book Review, Paris Review, Ploughshares, Poetry, Tin House, and included in multiple volumes of Best American Poetry. He is the Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Professor of English at Vanderbilt University.

LH: Within The Absurd Man exist a frenzy of characters and communities: we see Major being split in two characters, and we, as readers, also become a character in this world. There are also cloistered nuns, ancient Greek figures, and elegized poets. In “November in Xichang” you end with the phrase “we have only each other in the end;” and in “The Flaneur Tends a Well-Liked Summer Cocktail” there is the beautifully haunting idea that “perhaps, we manifest each other.” Can you talk about how other characters function in this world and what they mean to the titular “Absurd Man?

MJ: I cannot speak confidently about any particular design for the book in that regard, but will say, far smarter folks than me have discussed how we come into being through the relationships we cultivate and develop; this idea undergirds many of the poems. And yet, we remain a mystery to each other, even at times to our own family, loved ones, and even ourselves which makes sense if we consider the fact that we constantly evolve and, hopefully like the universe, are ever expanding. Another lyric condition of the book is that the speakers in these poems address the reader from a space of fracture, of meaninglessness, and seek wholeness which engages and quite importantly involves the reader. The late poet Stanley Kunitz states: “Sometimes the person you address in a poem is your other self, that Other who is also you. At other times you have to call on an outside agent, human or divine, to spring you from your self-made trap.” Several poems point to this; I am thinking of the opening poem “Major and I” in which the ending lines goes “Major needs lots / of sky. You are that sky.” and “You, Reader” which figures the reader as participating in the construction of meaning: “chalk of light over distant waters.” Meaning or the lack thereof, in the cosmic, existential sense, is the dilemma that drives much of the book. The titular title is drawn from Albert Camus’s construction of the Absurd Man in his book The Myth of Sisyphus who courageously faces the haunting fact that our hunger for clarity in a world emptied of meaning leads us either to ideological suicide or a confrontation of this condition with a freedom devoid of ideas of transcendence and value. In many ways, I divert from Camus because ultimately I believe in the transformative powers of art and poetry: “Tragically, he believes he can mend his wounds with his poetry.”

LH: There are many different registers, settings, and levels of lyricism in this collection which gives it a sense of vulnerable authenticity. At times you write of Dante, Titian’s Europa, Goethe; while, at others, you reference dance clubs, online dating, and kids dancing to Ariana Grande. Can you speak to the practice of representing various cultural registers within the same collection?

MJ: I appreciate this observation. I solidly believe the whole self needs to find space in a collection of poetry. Along with memory, those cultural registers are a way of authenticating a conscious mind that is not self-preoccupied, but present and aware to the world swirling around her. Otherwise, the speaker in a poem may sound hollow and indistinct. We are a constellation of experiences and our encounters with art, poetry, literature, music, philosophy give us breadth. As a reader, when I come across such volume of associations and allusions in a poem or book, I know the author is alive and collaborating with the age, attempting to make sense or leap into the unknown. And frankly, I have never quite honored those thresholds or borders that mark culture as either populist or aristocratic. Such declarations intimate an impoverished existence on earth.

LH: In Urban Renewal each section of the poem is an extended sonnet with end rhyme, which seems to work as an idea of “renewing” a traditional form. Many sections of the poem are panoramic and, at times, read as a rejuvenated, modern pastoral form. But there are so many other levels, like portraiture and social commentary. Can you discuss the inception and creative process for this poem ?

MJ: Urban Renewal began some twenty-three years ago while in graduate school at the University of Oregon. It is hard to believe. Intrigued by sonnet sequenced books particularly George Meredith’s Modern Love, Ted Berrigan’s The Sonnets as well as those that sought to renew, redefine, or exhibit the possibilities of the form, including extended sonnets: Robert Lowell’s Notebooks, Melissa Green’s Squanicook Eclogues, Derek Walcott’s Midsummer, among others. I was deep into John Berryman’s Dream Songs, too. I have remained committed to the project over four of my five books, each poem magnifying and advancing the vision of the project. More than the books I mentioned and the many that have been written since I inaugurated the project, writing the poems have taught me so much about myself. It has allowed me to cultivate a kind of ambition I think necessary for an emergent poet. It has also taught me the range of speech acts possible in a poem, what kinds of thematic and rhetorical tensions that are achievable. What started off as a desire to situate and honor the city of Philadelphia and its long history of music and art in my growth has emerged as part travelogue, part diary, part history of my obsessions..

LH: You also demand complexity when we consider desire in these poems. In most cases, when we are presented with desire or tenderness, we are also presented with violence or pain. What role does desire play in the concept of an absurd creator or in the existential world?

LH: That’s a tough question which I think gets to the heart of the book: desire, read broadly, as creation of our individual freedom but also, as you point out, desire as a theme addressed directly as either an affirmation of selfhood or the catalyst for harm; if the latter then also present are questions of redemption, guilt, and growth i.e. how to take responsibility and explain the causes of pain. I think several agendas might be afoot: the aesthetic aim of the book is for the text to embody desire or achieve an “erotics of reading” which I hope is the result of a reader’s willingness to exist in the interstitial spaces of signification and meaning, associations and linguistic and rhythmic figures that refract less fixed emotions or ideas but generally moods and momentary discoveries. The other agenda is probably directly linked to the Existentialists, particularly Camus’s notion of freedom and passion with desire as evidence of living in the present moment. Art is the one of highest forms of desire, as we attempt to impose our visions on the world, and yet, Camus would say also art is absurd because the act of creating only emphasizes our confrontation with and disquiet about an irrational world.

LH: “The Absurd Man Suite,” consists of twenty-five parts which ends with the poem “Double Major,” in which the two majors from the first poem are more united as an entity, seemingly symbiotic, but still separate. You mention negative capability in this poem, yet the epigraph at the beginning of the suite is the yearning for truth over doubt. How do these two ideas work together or coexist for you as a poet?

MJ: Yeah, I hear you. In the poem, the splintered self is less fixed of an idea or entity compared to the writerly public “Major,” less determined or realized, until given voice in a poem: hence the line: “I am negative capability. Test to all men are created equal.” which picks up a thread earlier in the poem about freedom and marries Keats’s questions of beauty and political agency, particularly the historic quest by African Americans for liberty: “his dreams are his father’s dreams . . .” I do not see the ability to live in doubt and uncertainty at odds with the perpetual desire for meaning or to imagine freedom. The urge to “make sense” is what takes us to our computers and canvases and dance studios. Not in all instances, of course, but ultimately we are examining life or searching for language or movement or sound that illumines the void. I think, too, the epigraph is also about naming and unnaming one’s trauma as a means of avoiding deception.

LH: In your Acknowledgments, you mention poems in collaboration with other artists. Especially in the time of COVID-19, I think a lot of poets are trying to carve out community wherever they can and perhaps struggling to create amongst the chaos. Can you talk about some of your experiences with creative collaboration?

MJ: This book features collaboration with two friends who are visual artists. I was delighted to work with my friends Jane Kent and Jill Moser. In both instances, their works were in response to poems that were already written and as I state elsewhere I could see more into my process as I watched them create prints and an art book that featured my words. In the past, however, I have worked with musicians, actors, and composers; at some point, the challenge is to synchronize to a point of imagination and replenishing. I also think patience and endurance are central components to any collaboration.

Major Jackson

Wonderland Trail

Writing birthed me

as well as the tropic zones of kindness

and the parables in the eyes

of my ancestors which belong

to the crickets talking in code

off a road in Longmire, Washington.

Once again I’m thinking

of Joe Wood on Wonderland Trail,

Joe who vanished into earth,

Joe whom I never discussed

the brassiness of tyrants

nor the pleasures of lousy coffee

or the peculiar sensitivity of

the willow flycatcher,

how we are found, thinking

with grace.

Blizzards trap light. I’ve seen

an elysian blue in snow holes

that bewitched my birth,

but who can discern

where darkness dwells?

Turn the searchlights back on.

A star is missing.

The coded voices

of birds thread

our emptiness.

True, all lives fade into a fog—

but it’s one of the small

mysteries here in America.

The Ocean You Answer To

The letter had not been sung

and the fire not yet delivered.

The traffic light caressed your thoughts and waited patiently.

Sunlight sizzled with onions and two tablespoons of olive oil

and a dark skillet yearned for its splash of garlic. All was still.

Unseen, many marveled in the comfort of their tiny utopias.

But you stood like music with your breath outstretched waiting for eternity

to enter your arms.

Some thought: this is the moment before the undertow of our lives.

Only a few considered the artist on the way to a first brushstroke,

or the prayer that would last like a comet

or the smile that reached the hand on a beloved’s hip.

Sunlight like golden leaves close to falling put you in the mind of Christo

and Jeanne Claude and the trailing swath of saffron rivering

above your head.

The ocean you answer to possesses a hint of infinity

like a neckline,

like crosscurrents in June.