So Kurt breaks all the rules and everybody loves him. Oh, please, don’t even get me started. Kurt’s like a little kid. Are we there yet, are we there yet? We get it. We got it the first forty times. Enough already. So, Kurt, if there really is a heaven, and you’re up there writing your crappy books, let me just say: Don’t repeat stuff over and over and over. And over. Ha-ha. Get it? And they say lawyers have no sense of humor.

My daughter and my wife used to go on and on about what an idealist Kurt was. And a romantic. About how people learning to be kind to other people was the most important thing. They agreed that what Kurt was saying in everything he wrote was: People, be kind to each other. Take care of each other. Be good to your planet. Make sure everybody has food to eat. Only create machines and religions and governments that help people feel strong and peaceful. Love as often and as sweetly as you can. All that made Kurt a romantic, they said.

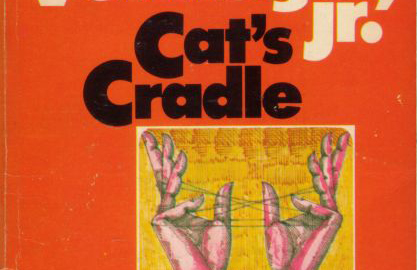

Kurt a romantic? Hah! What the hell was he trying to say about love in books like Cat’s Cradle and Mother Night?

For our fiftieth wedding anniversary, the kids gave Mary and me a beautiful surprise party. They knew exactly what we would want. It was just family; none of the people I was always pretending to like were invited. It was in the same lodge where Mary and I had gotten married, up in the mountains and beside a lake surrounded by pine trees. After we ate, we all went out onto the stone porch where Mary and I had said our vows. It all felt so great, I didn’t even know what to do with myself. Meghan made the toast. This is what she said:

“Dad’s good friend is Kurt Vonnegut, a man whose books, back when I was in high school and college, were practically required reading for everyone I knew. Not for classes, but for our own minds. We all read and loved and quoted Mr. Vonnegut’s books. Of course, that was many years ago, but when I started thinking about what I wanted to say to Mom and Dad here today, out of nowhere and over all those years, it hit me. In one of his books Mr. Vonnegut has a made-up language. One of the words in that made-up language is karass. It means a team of people who together carry out God’s will without ever knowing they are doing it. Another is duprass, the rarest and most unique form of karass, because it is a karass made up of only two people. In another book, Mr. Vonnegut describes a couple who are a Nation of Two, complete and whole unto themselves, who have no purpose and no meaning, one without the other. After all this time, these stories came to me instantly because I remembered that when I read them for the first time, when I was sixteen years old, I believed they described my parents. And I still do.”

Meghan went on some more about what a great team we were, Mary and me, and at the time I thought it was just the nicest thing. But now when I think about it, it’s not such a compliment. Imagine that, Meghan saying Mary and I were like the Mintons in Cat’s Cradle, two old farts who didn’t care about anybody but themselves, preferring to share private, little jokes between them while the world fell apart. And Howard W. Campbell and Helga and Resi Noth in Mother Night. They weren’t even a Nation of Two–wasn’t that the joke of it, that there were three of them in that little country? And that their true love didn’t cancel out all the bad things they did? And Mary and I thought it was such a lovely thing when our daughter held up that champagne flute and called us Nazis. [6]

And Kurt, I wonder what he would’ve thought if he’d been there. Probably something like this: Gee whiz, I sure am glad those kids have no idea what I’m talking about. Got their money, got their love. Yee-hah. Kurt was no romantic. That whole karass thing was a joke. Doing God’s work. I mean, for Christ’s sake, the man was an atheist! And these idiot college kids, what did they learn from Mother Night? That it’s okay to be a Nazi as long as you’re in love? I don’t think so. No, Kurt, you failed again.

Just yesterday, I was thinking about all that and called Meghan into my study to have it out with her. She’s been staying over at the house since Kurt died, and I guess she thinks I’m acting kind of creepy, sitting here in this study all day. I get confused sometimes, the old synapses not shooting off so well. But I’ve just got to think about things.

At first, I yelled at Meghan; I was so hopping mad at . . . well, I’m not really sure at what, but it had something to do with trying to understand Kurt’s stupid books and getting all mixed up about everything.

After I was done yelling, I sat with my hands clasped between my knees. Meghan wrapped her arms around me and rested her cheek on the top of my head. We stayed that way for a while, and things didn’t feel so horrible. I felt the weight of my daughter’s cheek taking my headache away.

When Meghan went into the kitchen, I tried to feel her arms still around me. I thought, there are so many things to think about and not enough time. Do I believe in God or not? Should I be glad no one’s sleeping on the sidewalk in Times Square anymore, or should I hate that it’s just like the suburbs now, with Disney and the Gap and the Olive Garden? It’s complicated. It’s so complicated. I keep looking for all the connections. Sometimes they come at me like the meteor in a 3-D movie and then I get scared, and sometimes they whisper at me from their hiding places, and I know they’re laughing. Nothing’s the way it used to be.

I don’t even know what I’m saying here anymore. I’ve had too many drinks, and I’ve had them alone. God, but I miss Kurt. Good-bye, my friend, good-bye, good-bye. Goddamn you for leaving me here without you. [7]

6. I know you know I wasn’t calling you a Nazi. I can’t believe I even have to explain this. It was the idea, the idea that you and Mom were so good together, had a kind of love that made everything else irrelevant. So stop doing the lawyer thing and turning everything around. And you wondered why I laughed when you talked about me maybe going to law school.

7. Oh, Daddy, I keep reading those last few sentences and seeing you in that old office chair, surrounded by books and papers, newspaper articles and plaques and certificates. And framed photographs everywhere: on the walls, scattered around the desk, crammed in bookcases. Formal ones: your wedding, all our proms and graduations, the family portraits. And the snapshots. The reunion at the lake. You and Mom dancing at the Governor’s Ball. That one I hate of me in the bathtub when I was three. And the one of you and Mr. Vonnegut in Dresden. You touch our faces and then the chair squeaks as you turn back to your tape recorder. You are holding it so tightly, your fingers are numb. You wear the same face you did after Mom’s funeral. Do you remember? When I was leaving, you wanted me to stay, but knew you couldn’t ask, knew that in a moment, you would be alone. You’re thinking so hard, trying to figure it all out.