Nikolai Grozni

Freaks

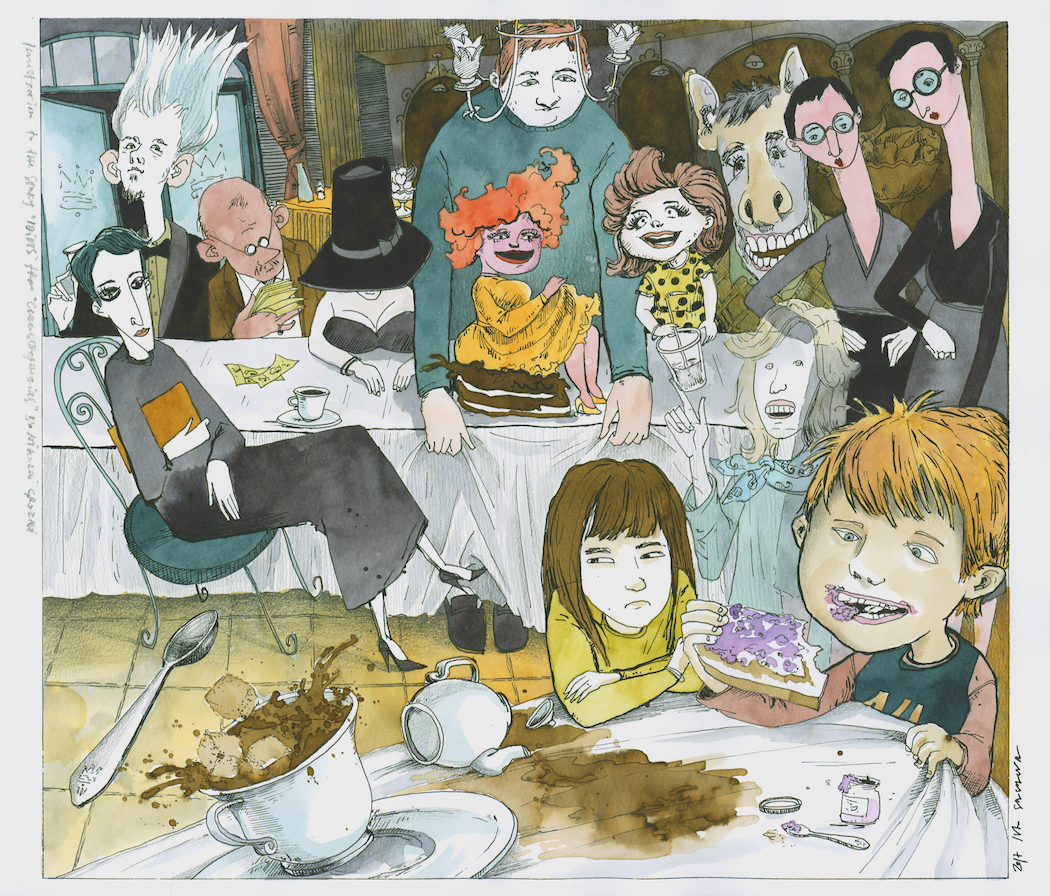

It was more or less like this: the town, a drab, Alpine lair on the Italian-Swiss border, had a long, unmemorable name which started with C; the hotel was a mediocre mortuary for seasoned visitors and was run by three generations of short-haired women with glasses; the purpose of my visit had at one point been explained to me by my former wife, but I have since forgotten both the purpose and the name of my former wife, though I’m inclined to think that she and I must’ve had some children together because, if I remember correctly, when we sat down for breakfast the first morning there were a few children sitting in the chairs adjacent to us, demanding jam and toast and discussing the surroundings with great impertinence. It was really early in the morning, ten or eleven, and I had just begun to stir the sugar cubes piled up to the rim of my coffee cup, trying to avoid the insolent faces of the children and the ambitiously sculpted wisdoms falling out of my former’s wife mouth like death masks, when the French doors swung open and into the dining hall lumbered a large group of circus-rate freaks guided by the wavering wand of a tall, black-cloaked woman with a triangle face whose only claim to normality appeared to be based upon her indisputable possession of a wallet. One by one the freaks sat around a long, apostolic table and started performing their well-rehearsed tricks. My attention was first drawn to a miniature woman with an enormous head, in a polka-dot dress and patent leather flats, who spoke in a tiny voice and giggled uncontrollably at her own jokes, wrapping her short, baby arms around her head and waggling her legs which barely reached the chair’s edge. Noticing that I was looking at her from across the hall, she froze, her eyes distending, and nudged the donkey-headed man sitting next to her, whose primary occupation was to roll his long tongue in and out of his mouth and hee-haw loudly, stretching out his neck to better examine the assembly. Presently, the donkey-headed man noticed me as well and nudged the giant sitting next to him, hee-hawing and pointing at me with what could only be interpreted as great affection. The giant, whose head was caught in the chandelier and whose hands extended across the table, didn’t respond right away, and that, admittedly, was quite fitting, since his main concern appeared to center on the exigencies of free will and, in particular, on the initial impulse that set a scene in motion: there had to be a button, he seemed to think, with his head caught in the chandelier; there had to be a button that pressed the button, and one could not but press, again, the old question regarding causality: which came first, then, the button or the button? The button, I replied in place of the giant, detecting with some annoyance that my disclosure had not failed to elicit a certain flurry of scrutiny on the part of my former wife and the contemptuous children; nor had they failed to notice that I had spilled my coffee and, presently, was pulling the tablecloth and the entire breakfast arrangement onto my lap, owing to the fact that, while attempting to balance the chair on its hind legs, I had inadvertently reached its tipping point and now risked falling backward and smashing my head on the table behind me. The sound of the porcelain tea pot shattering on the terrazzo floor attracted the giant’s attention and now our eyes met, his and mine, and it was self-evident that I saw myself through his eyes, and he saw himself with my eyes; and whereas I grew instantly attached to his giantness, he grew forthwith attached to my nonexistence, and as time passed, I felt more and more giant-like, whereas he felt more and more nonexistent; and had someone asked us, at that moment, who was the giant and who was the reality hole, I would’ve answered that I was the giant and he would’ve most certainly answered that he was the reality hole. He had advanced so far into the reality hole, in fact, that had he not found in himself the strength to bend over the hatted lady with one long and one very short arm sitting to his right and shout in her ear to look at me, pronto, he would’ve likely disappeared for good. But he didn’t disappear, and I didn’t grow so big as to knock down the roof of the hotel. I stirred my third cup of coffee with my pinkie and looked right through my former wife’s rather transparent head, even as she tried to articulate a purely scientific explanation for the somewhat bizarre circumstances that led to my tea spoon flying into the face of the charming octogenarian sitting in the corner of the dining hall. The hatted lady with one long and one very short arm was winking at me and demonstrating her ability to drool inordinate amounts of mouth liquid into the crevice between her giant tits—a feat of smashing ingenuity which I promised my self to study more closely in my private quarters at a later time. One of the children had asked me a question, something about midgets, or quantum mechanics, and I answered mechanically, giving my full attention to the balding bookkeeper with a nose bent severely to one side who was counting a wad of fake banknotes and yelling at the hatted lady to stop drooling. I too wanted to count wads of banknotes, fake or otherwise, and distribute them among the hoi polloi in exchange for a small service fee. The bookkeeper was well aware of my interest in his machinations and didn’t consider it necessary to conceal the sleights of hand which made his machinations profitable. He looked at me, I looked at him, and we came to an agreement: I would count and deal the banknotes using his hands and tongue, taking full advantage of the legerdemains which he’d perfected after years of relentless practice; he, on the other hand, would follow my former wife to her private quarters and try to seduce her, using one or more parts of my body and taking full advantage of the nearly metaphysical indifference which she and I exhibited in each other’s presence at all times. This, I thought (getting up, briefly, to dispossess the rather obnoxious individual sitting at the table to my left of his second plate of bacon and toast), was indeed a magnificent proposition, and, loath to delay this matter any further, I nodded to that effect at the bookkeeper and he nodded back, elbowing the very nervous virtuoso with gray hair sticking on end, sitting on his right, to take notice of what had taken place and step forth as a reliable witness: which he did, faithfully, pulling his ears, growling like a dog, and smashing his forehead against the table seven times in a row. There was, I noticed now, a lively disagreement underway on the margins of our table involving my former wife, the obnoxious individual and two of the three short-haired women in charge of the hotel, and from what I managed to gather with one ear, it appeared that the central premise which the obnoxious individual had put forth revolved around the idea of his preordained and unassailable jurisdiction over his second plate of toast and bacon, whereas my former wife argued that his so-called unassailable jurisdiction over the plate of toast and bacon did not preclude her from having a completely irrelevant and contradictory opinion on the subject, which I thought was a rather weak argument, and as the obnoxious individual took issue with my former wife’s argument and then went on to decimate it didactically point by point, I found myself growing increasingly fond of him and made a note in my journal to study his tactics for future use. The disagreement ended suddenly when the red-haired concubine without teeth, who had until then cuddled next to the very nervous virtuoso, climbed onto the table, on the recommendation of the very nervous virtuoso, hiked up her skirt and sat on top of the chocolate cake placed before the unseemly fat woman with an alphabet fixation, thereby drawing a round of applause from all the guests at the apostolic table who appeared genuinely impressed by acts of disinhibition and spontaneous regression and turned a blind eye to the disdainful reaction of others, less inspired beings. The fact that I, too, was genuinely impressed by the toothless concubine’s cake-smeared buttocks, and the subsequent attempt by the bookkeeper to eat the wallet and then the entire hand of the black-cloaked lady with the triangle face, was not lost on my former wife and the children, nor, for that matter, did the guests at the apostolic table fail to notice that I longed to join them and shake off, once and for all, the pretense that I was real and that I understood, wink-wink, the so-called decorum of existence, whereas I understood absolutely nothing of the so-called decorum of existence and existed from day to day by employing acts of trickery and metaphysical acrobatics which rivaled the creation of the universe, from scratch, or from a dung beetle, or from the ball of dung pushed by a dung beetle. For while others appeared to simply exist, abiding effortlessly by the accepted reality, I had to convince everyone around me that I was one of them and that I also abided effortlessly by the same reality, even though I couldn’t see even the outline of the so-called reality and merely performed the tasks that had been described to produce real results, in the hope that everyone would be fooled and I would continue to live among them, wink-wink, like a wolf among sheep, or a frog among pebbles. It was undeniable that the whole thing smelled profoundly of sympathetic magic, spells, and heavy superstition, and I was tired of pretending that magic spells worked, when in fact they didn’t work at all, or, at best, succeeded in making those involved miserable in a very real way. I just wasn’t one of them, I thought, noticing how one of the children, maybe a boy, poured himself another cup of hot chocolate and looked at his mother with a sense of historic achievement, disregarding the possibility that both he and his cup of hot chocolate may have existed only as a pair of slippers inside a very brief and insignificant dream dreamed by an ordinary baby maggot attached to the testicles of a leper dog at the Bidhan Nagar Road rail station in Kolkata. Wink-wink, I winked at the miniature woman with enormous head and tiny voice, who was smiling at me and pushing a plastic straw far up her nose. Wink-wink, she winked back at me, not without a tinge of sadness, for she knew as well as I did that I was rather trapped in my social arrangement and could not join her and her companions just like that, on a whim, lacking advance preparations or at least a few pieces of incontrovertible evidence linking my former wife and the children to the workings of the Gestapo and, before that, by way of metempsychosis, to the illiterate hordes of savages responsible for the sacking of Constantinople. Wink-wink, the very nervous virtuoso winked at me, as he pushed himself away from the table and fell backward in his chair, pounding the terrazzo floor with his reverberant baroque head. They were all leaving now, the freaks, taking their fabulous tricks and vaunts somewhere else, and they were going there without me. I belong with the freaks, I thought, or maybe I even said it out loud, I couldn’t tell for certain, and the inscrutable expressions on the faces of the three creatures sitting at my table prevented me from forging a well-informed opinion on the subject. I still had a lot of work ahead of me before I could disengage from the so-called decorum of existence and step lightly across to the other side. Without a doubt, the day would come when I would join the freaks and leave all these drab dolls and their obsessive-compulsive reality rituals behind. I would shake and stick my fingers in my eyes and hop around like a rabbit and bark like a rabid dog. I would walk and sit whichever way I wanted. I would use mixed metaphors and non sequiturs to describe the authorless figment known as reality and achieve nonconceptual love for all living beings, including humans and meerschaum pipes, by attaching myself to the testicles of a leper dog at the Bidhan Nagar Road rail station in Kolkata and surrendering to the spontaneous visions of an uncreated, jalebi-sweetened reverie. Oh, the day would come, the day would certainly come when I would join the freaks and leave all these lies behind. Then, and only then, would I be born for the very first time.

The Death of a Village Postman

At some point during my stay in the village of A. (a funereal medieval slum which can be located easily on any odd map of Languedoc as it lies equidistantly between the town of S. and the village of G.), I took up residence in the immense, three-street-bound chateau known for its exquisite arrowslits, trefoiled stained glass windows, spacious courtyard, and a network of underground tunnels dating from the time of the Inquisition. The pretext for this rather bizarre déménagement, or change of address, appears to have been forged, in large part, as a consequence of certain conjugal obligations, though, I am told by my lawyer, all the available circumstantial evidence seems to suggest that my marriage—in this case probably my third—had reached a state of rigor mortis at a much earlier date than had been previously reported, which would imply that I had moved into the tiny, sunless, rez-de-chaussée atelier in the cold and damp northwest corner of the chateau, facing Rue Droite, either accidentally, by reason of blackmail, or due to a momentary impairment of my logical faculties. At eleven fifteen in the morning on the fourteenth day of September, exactly six and a half months after I’d taken up residence in the chateau, I walked into my atelier carrying a silver tray with a pot of black tea and a pitcher of cream, and sat at my desk, determined to refute, once and for all, the entire string of accusations which Monsieur Galopin, the former owner of the chateau, had put forth in the seventeen letters he had sent to me since his arrival in Tunis. I inserted a blank piece of paper into my 1930’s Royal typewriter, rolled the platen knobs until the paper popped into view, and wrote, Cher monsieur Galopin. Then I poured some tea into a cup, added a pinch of cream, and took the stack of longhand letters onto my lap, noting, not without a tinge of indulgence, that starting from letter number eleven onward the style of handwriting showed significant deterioration, which was coincident with Monsieur Galopin’s second stroke and his decision to marry his Tunisian cleaning lady who, according to the local papers, happened to be twice his height and forty years his junior. It was interesting to note also that even as his handwriting began to appear more and more feverish and chaotic, his line of reasoning concerning the fate of his various appurtenances—the Louis XV armoire, the pair of nineteenth century Anduze vases, his wine bottles, the Murano glass chandelier, his black cat named Napoleon, and the two hundred thousand franks in a macaron box which I had agreed to place in the trunk of a white Peugeot owned by a certain Monsieur Barbu—acquired an unexpected lucidity and coherence, to the extent that even his threat to return to France and shoot me in the groin with his revolver from the Algerian war sounded quite principled and dignified. I placed the letters on the desk, walked to the window overlooking the decrepit stone wall of a long abandoned three-story house with a pigeonniere, and examined both ends of Rue Droite, wondering why the postman had not yet delivered the mail. Glancing at my watch, I returned to my desk and fixed my gaze on the massive backdoor key which I used primarily as a paperweight. Before I could attempt to redress Monsieur Galopin’s more serious grievances, I thought now, formulating the order of my response in my head, I had to, first and foremost, confront his insinuation regarding the so-called theft of his infamous wine collection, for, had I not discovered the rotten, ash-covered boxes with wine under the putrid carcass of what the plumber, who’d come to examine the leak in the basement, described saturninely as “un sanglier préhistorique”, I would not have found myself into the present predicament, having to clarify, at gun point, as it were, the circumstances leading up to what Monsieur Galopin callously referred to as “la grande catastrophe”. For even if Monsieur Galopin managed to provide witness testimony affirming his contention that, on the day he’d given me the final tour of the chateau, he and I had reached a gentlemanly agreement regarding the proprietary rights to the wine collection in the cellar, he would be hard pressed to convince anyone with even a mild resemblance to homo erectus that I had actually understood a single word of what had been stipulated in the so-called gentlemanly agreement, owing to the fact that Monsieur Galopin spoke as if he had a big chunk of camembert stuck permanently to the back of his throat and was so minute that oftentimes, walking along the dark corridors in the north side of the chateau, I found it difficult to distinguish him from his scruffy terrier, especially since both Monsieur Galopin and his terrier made the same snorting noises and smelled of cigarette smoke and century-old Persian carpets. But even if I were to concede the existence of the so-called gentlemanly agreement, Monsieur Galopin wouldn’t have a leg to stand on, considering that he’d promised to send someone to fetch his wine collection and bring it to Tunis before his seventieth birthday in May, and when the plumber came to fix the leak in June, the wine collection was still in the cellar and I had no other choice but to remove it, together with the wild bore carcass, since not doing so would’ve resulted in the bursting of the main pipe and the consequent flooding of the cellar. Having established the initial circumstances in such a way as to preclude Monsieur Galopin from referring to the loss of his wine collection as the “vol de bouteilles de grands crus”, I could proceed to demonstrate that what happened next was not only inevitable, but also quite unnecessary, or vice versa. For I had hardly reached the top of the stairs leading out of the cellar, with two of the seven cases of wine in my arms, when the bottom of one of the cases fell through and the wine bottles dropped one by one on the hard stone stairs, breaking into pieces and splashing wine across the walls. Of the twelve bottles I dropped on the floor, three shattered into the tiniest shards, another two lost their necks, and the rest remained miraculously intact. Thankfully, Monsieur Poivrot, the plumber, was right behind me, and when I teetered, weak-kneed, to the edge of the staircase, he immediately dropped the two cases of wine he was carrying and helped me regain my balance, drawing my attention to the fact that the spilled wine not only possessed the ghastliest coloring of any fifty-year old Bordeaux the world had ever seen, but also emitted powerful and strangely odious vapors, whose toxicity could easily knock down a horse, or a two-hundred kilogram wild bore—which could go a long way toward explaining the presence of the putrid carcass in the cellar. Monsieur Poivrot, I was surprised to discover, was a reputable enologist specializing in uncommon vintage Bordeaux and dabbled in plumbing on the rarest of occasions and only with a view to please his ninety-seven year old father, who was in fact considered the father of plumbing, so to speak, not just in the village of A. but in all the surrounding areas as well. This information was conveyed to me by Monsieur Poivrot himself on the way to the kitchen where he, in his professional capacity, recommended that I immediately decant the wine from the two bottles with broken necks so that he could have some time to examine the quality of the wine before it turned to vinegar. The procedure, involving two carafes and a sieve, had to be executed within minutes of the wine’s exposure to oxygen, Monsieur Poivrot explained, for we were dealing with two ’46 Pessac Leognan vintages whose corks had evidently started to descend months before the bottlenecks were inadvertently chopped off on the cold cellar staircase. After having two glasses from each carafe, Monsieur Poivrot concluded that the wine wasn’t quite as tragic as he’d previously assumed and allowed me to pour myself a glass and take a sip. In truth, the wine was almost drinkable, if a tad unremarkable, its main defect being that it was just too old. Monsieur Poivrot drank quickly, concentrating his whole being on the tip of his nose, and when we had finished the carafes, he volunteered to fetch the other two vintages with broken necks, appelation Grave, 1952, which had fallen out of the two boxes he’d carried at the time I had slipped on the stairs. In order to make matters less confusing, I thought, sitting at my desk and mapping my future letter to Monsieur Galopin in my head, it would be practical to include a simple diagram explaining clearly, and without unnecessary deviation, the math behind this rather complicated transaction. To begin with, I had carried two wine crates, each holding six bottles; three bottles were shattered completely, two had their necks chopped off without spilling much of their contents, and another seven were left largely intact. Similarly, Monsieur Poivrot carried two crates with twelve bottles in total of which two bottles were shattered completely, two had their necks chopped off, and eight were left largely intact. Of the fifteen vintages which were left largely intact, thirteen were on the verge of turning into downright plonk unfit for use even in a bad salad dressing; Monsieur Poivrot proved this last point by demonstrating that he could push the corks down the bottlenecks using nothing but his thumb and applying only a minimal amount of force. Any cork that could be dislodged in such a way, he argued, sticking his thumb in all thirteen of the fifteen solid bottles, is simply no good and in all likelihood is already rotten. Only two bottles stood up to Monsieur Poivrot’s thumb test and so we set them promptly aside in the arrow-slit embrasure for future consideration. Naturally, with Monsieur Poivrot and I engaged in the deleterious, fight-against-time battle to analyze all thirteen possibly exquisite vintages on the verge of turning into downright plonk, it took us some hours before we could leave the kitchen and descend into the basement to check on the pipe leak in the cellar. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that both Monsieur Poivrot and I were rather surprised to discover that in our relatively short absence the once innocuous puddle on the cellar floor had grown into something potentially much bigger and grimmer which, judging by the way that the wild bore floated menacingly across the chamber with its huge tusks pointed at us, had all the markings of a full-blown inundation. Braving the strong currents and the treacherous jabs of the wild bore’s tusks, Monsieur Poivrot dived into what could only be referred to as a river and extracted, one by one, all three of the remaining wine boxes from the bottom. It was then that I slipped up for the second time on the stairs, on account of the snails and the slimy fish, and hit my head on the stone threshold, disengaging, at once, from the three wine crates I was carrying in my arms. Though this experience left me in a state of moderate-to-severe bewilderment, I managed to gather enough strength and dived, together with Monsieur Poivrot, into the river for the express purpose of collecting all of the surviving vintages. With the tide rising rapidly, Monsieur Poivrot and I succeeded in bringing the last bottle out of the cellar and closing the massive cellar door just as one of the basement walls collapsed and the river flooded the ancient tunnels left from the time of the Inquisition. It should be noted that Monsieur Poivrot did not at any point neglect his duties as a plumber; on the contrary, he assessed the situation on a regular basis and made exhaustive plans to deal with the problem the moment the torrential rains would begin to subside, which, he informed me, was the standard practice in these circumstances. While we waited, Monsieur Poivrot examined the fifteen bottles we had extracted from the river and concluded that every single one of them had a sagging cork, even the ’54 Saint-Émilion grand crus whose cork appeared, at least to my untrained eye, rather solid. It is hard to pinpoint the exact hour when Monsieur Poivrot decanted the first of the fifteen remaining vintages, but what I could say with great degree of certainty is that it was night and the church bell had stopped chiming; that would logically place the whole episode sometime between one and five o’clock in the morning. There wasn’t much deliberation in the way in which Monsieur Poivrot classified the wine: some of the bottles were drinkable, the others less so. While I agreed with his appraisal of the wine and his view on life in general, I did not hesitate to challenge his position on the uncorking of the two bottles of wine we had earlier set aside in the arrow-slit embrasure. For whereas he claimed that I had asked him to open the two untouchable bottles, in view of the fact that we had finished all the other wine, I was of the opinion that he had either misunderstood what I had said to him—as it often happened when I spoke French around the village—or he had opened the bottles on a whim, forgetting the reason why we had set them aside in the first place. Regardless, the wine in the last two bottles turned out to be utter plonk and we drank it only out of deference to the otherwise respectable vigneron. We were still finishing the last carafe when Monsieur Poivrot noticed the Louis XV armoire floating across the lower-level living room and then exiting, abruptly, onto the courtyard via the French doors, which burst open under the force of something roughly approximating the Nile in high tide. Monsieur Poivrot, to his credit, was quick to dissuade me from running downstairs, explaining that the worst part of the inundation was now over and that from this point onward he expected to see the waters ebb away and disappear. As for the exquisite Louis XV armoire, Monsieur Poivrot felt less optimistic, saying that though the armoire would continue to perform the basic functions that have been built into its design, it would henceforth be considered a piece of wothless junk with chipped and curled-up two-hundred-and-fifty-year-old lacquer. On that note, he put his hat on and descended the back staircase to the courtyard where he’d parked his Citroën deux chevaux. This must’ve happened at approximately eleven fifteen in the morning, for I remember hearing the mailman’s Vespa scooter howling down Rue Droite like a German dive bomber shot out of the sky, its annoying honking dampening the sound of crumpled metal and broken clay as Monsieur Poivrot backed up not once but twice into the monumental, three hundred-year old Anduze vases standing in the center of the courtyard. Indeed, a sorry fate for the vases and Monsieur Galopin’s black cat, named Napoleon. Lastly—I thought now, sitting at my desk and trying to organize the sequence of events in a clear and logical order before putting them down on paper—I had to prove to Monsieur Galopin, quoting selectively from his letters to me, that his bourgeoisly obfuscating style of writing, not dissimilar from his style of speaking, set the stage for all the misunderstandings that were to follow. For whereas his written instructions stated in no uncertain terms that I should place the macaron box with two-hundred thousand franks in large bills in the trunk of a white Peugeot belonging to certain “Monsieur Barbu” and parked on the corner of Rue Droite and Richelieu on the seventeenth of June—the day when the plumber knocked down the Anduze vases—it would’ve required a diviner of Pythian proportions to discern that the so-called “Monsieur Barbu” is not in fact someone bearing the surname “Barbu”, as in Pierre Barbu, but, rather, a monsieur with a completely different surname who just happened to have a beard. The counterargument that no French speaker with an intelligence above an amoeba could’ve misconstrued “Monsieur Barbu” to mean someone with the surname Barbu, when, supposedly, almost all French speakers upon hearing “Monsieur Barbu” would instantly imagine a bearded monsieur, is simply not feasible, because when I ran out of the back door onto Rue Droite on the seventeenth of June and asked the mailman if he happened to know “Monsieur Barbu”, I did not in any way specify whether I meant a bearded man, or someone with the surname “Barbu” and left it to the mailman who, being a native French speaker with an intelligence presumably above that of an amoeba, was fully qualified to determine the meaning of these two words without having to consult a dictionary as I did on the eighteenth of June. The mere fact that the mailman, notwithstanding his ability to operate a two-wheeled open motor vehicle and to complain incessantly about the height of my mailbox, not only misconstrued the meaning of “Monsieur Barbu” but went even further, misspelling “Barbu” in his head and imagining it as “Baribeau”, which happened to be the surname of the mayor’s secretary who had at that precise moment parked his white Peugeot outside the epicerie on the corner of Rue Droite and Richelieu, speaks volumes for the state of the French education system and the intelligence requirement for working at La Poste. For even after I had placed the box of macarons inside the trunk of the white Peugeot parked outside the epicerie and Monsieur Baribeau, the secretary to the mayor, drove away with his bag of asparagus and the two-hundred thousand franks in large bills which I had agreed to pay Monsieur Galopin for the Louis XV armoire, the Anduze vases and the Murano glass chandelier—without alerting the tax authorities whose ubiquitous agents, in Monsieur Galopin’s words, had the indecency to follow him even in the bathroom and, were the chance to arise, would not hesitate to stick their dirty fingers in his pockets while he lay dying in the gutter—the mailman continued to insist that he could not for the life of him hear the difference between “Monsieur Barbu” and “Monsieur Baribeau” and was not planning to lose any sleep over it, whereas Monsieur Poivrot, who returned on the eighteenth of June with an experienced antique dealer, was of the view that Barbu was Barbu and Baribeau was Baribeau and there were no two ways about it. The antique dealer, who examined the allegedly priceless Murano glass chandelier from Casanova’s palace and, after declaring it to be a shameless forgery, bought it from me for a hundred franks, concurred with Monsieur Poivrot and put the blame squarely on the mailman, describing him as a raving lunatic and a waste of space lacking any utility or purpose. It was all the mailman’s fault, I thought to myself now, sitting at my desk and composing my final response to Monsieur Galopin in my head. I pictured the mailman quite vividly, his bloated face and piglet eyes without eyelashes, his blue uniform and yellow helmet inscribed with the logo of La Poste; the way he would rev up the engine of his mustard-colored scooter and dash from mailbox to mailbox, honking belligerently at the stray cats; the way he would stop in the middle of the street, blocking traffic, and reorganize all the letters in his leather bag, rubber-banding them into ever smaller bundles; the way he would always snort at the sight of my mailbox which, at the height of hundred and twenty-five centimeters (five centimeters above the height recommended by La Poste) required that he stand on his feet in order to reach the mailbox slit; and then, there was his maddening voice of a duck with a severe sinus infection and a split tongue. But I wasn’t only imagining him: he was actually right below my windows, revving up his scooter and quacking his incomprehensible orders at the members of the public. The arrogance of the man, I thought, checking my watch. He was nearly an hour late and had the nerve to honk and shout as if he were the most important person in the world and everyone had to stop everything they’re doing (like reading the papers or finishing their letters) and go out into the street to greet him. I opened my windows and caught him in the act of throwing a bunch of letters at the back door of the chateau, on account of the fact that standing up and putting the letters through the mailbox slit would’ve obviously required too much exertion. I tried to express my disapproval of his behavior by shouting out the standard French expressions used in such circumstances, but my voice was drowned out by the growling and sputtering of the scooter, and soon my lungs filled up with searing diesel exhaust and I began to cough uncontrollably. In retrospect, it is hard to say when exactly I lost faith in the reality of the situation or, conversely, when the reality of the situation lost faith in itself, but, having experienced frequent episodes of reality-loss during what I like to refer to as my Great Indian Unraveling, it is safe to assume that I recognized all the signs of the impending rupture much earlier, perhaps as early as the somewhat disorienting night on the seventeenth of June, and when the mailman continued to throw letter after letter at the steps of the chateau for what felt like hours, submerging the entire Rue Droite in a cloud of diesel exhaust, I knew that even if I hurled the massive, two-kilogram key at him—the key I used as a paperweight and which appeared as the only suitable projectile on my desk—the consequences would be either very queer or entirely nonexistent. In truth, the key hit the mailman’s helmet straight on, producing a loud bang echoing in both ends of Rue Droite, but the mailman remained unperturbed and continued dumping his mail at my doorstep, refusing to acknowledge my presence or the fact that his scooter had poisoned the entire village. There was something very strange, if not suspicious, in the way that the heavy key bounced off the mailman’s helmet and evaporated in thin air, I thought to myself as I left my atelier, walked across the vestibule and the sitting room, exited out onto the courtyard and went inside the decrepit garage which contained fragments from an ancient olive press, rotten wooden beams, saddles, scythes, Napoleon III half-beds, copies of La Republique dating from 1917, and a chest with a corroded nineteenth century double-barreled hunting shotgun and a dozen soiled cartridges. I placed two cartridges in the breech ends of the barrels, returned to my atelier, and sat on the windowsill, pointing the shotgun at the mailman. I didn’t actually plan to shoot at the mailman or his scooter. My intention was simply to count from ten to one backwards, in French, and see if the mailman would get the point and scamper away. To say that I was caught by surprise when, reaching seven, the shotgun suddenly went off with what sounded like a cough, producing a coil of acrid smoke, would be a bold understatement, considering the shotgun’s age and shape, and the fact that my finger didn’t even touch the trigger. I may never know which bullet actually hit the mailman—the first one, which was discharged when the shotgun fired off by accident, or the second one which was discharged when, jolted by the shotgun’s unexpected behavior, I impulsively squeezed the trigger. In reality, if one is allowed to speak of such a thing, the mailman didn’t appear hurt and there was no sign of a bullet wound anywhere on his body. He remained seated on his scooter for about a minute, then tilted to one side, as if to check on the sputtering engine, and dropped stiffly on the ground. Madame Bouchard, who happened to be passing by on her way back from the epicerie, didn’t seem very bothered by the sight of the mailman lying in a pool of purple blood. She greeted me casually, put the mailman’s leather bag over her shoulder and scurried up a side street. Next came Alex, the truffle man, pushing a wheelbarrow. He greeted me joyfully, mentioning the sun and the pesky mistral, then placed the mailman’s body inside the wheelbarrow and headed home, explaining with a wink that he needed the body to rejuvenate the soil in his garden. Five minutes later, when I returned from the kitchen with a glass of cognac, the scooter was gone, the letters were burning in a heap of dead leaves, and the stray cats were licking what remained of the blood puddle. I sat down at my desk, glanced over the three words I had typed so far, and added, “J’ai tué le facteur.” That, I thought, explained everything. I removed the letter from the typewriter and, folding it nicely, slipped it inside an envelope addressed to Monsieur Galopin. Then I put my hat on and climbed out of the window. I had five minutes to get to the post office before it closed for lunch.

Nikolai Grozni began training to become a classical pianist at the age of five. He won his first piano award in Salerno, Italy, when he was ten, and continued winning awards and performing until his untimely dismissal from the music high school in his native Sofia. He moved to Boston to study jazz and composition at Berklee College of Music, but, having set his sights on the pursuit of the transmundane, he suddenly left for India to become a Buddhist monk and study at the Institute of Buddhist Dialectics in Dharamsala. Five years later he disrobed and returned to Sofia, ostensibly to focus on his writing. Since then Grozni has received an MFA from Brown University and published five novels, including the acclaimed Wunderkind; one memoir, Turtle Feet; and a collection of dream stories, Claustrophobias, all the while working on his photography and traveling in triangles between Bulgaria, France, and the US.

Iva Sasheva is a master printmaker, painter, sculptor and book illustrator. Her first exhibition at the age of thirteen was followed by number of solo and group shows in Europe and America. As an artist she has contributed her work to more twenty-five feature films and collaborated with authors in the creation of several graphic novels, literary novels and children’s books.