Teodora Dimova

I’ve always aspired to take the romantic halo away from writing—the inspiration that wells up uncontrollably from within and pursues you everywhere you go, the dictation from God that you just have to listen to closely and simply write down, in the middle of a garden with warbling birds and Japanese cherry trees. I’ve repeatedly said that writing is heavy labor, that it is thankless and everyday work, filled not infrequently with irritations, and sometimes with tedium or a feeling of complete helplessness. That it requires self-discipline, spiritual asceticism, the concentration of a surgeon during an operation, the focus of a priest during mass. That this state does not suffer verbosity, the pettiness of everyday life, the stupidity of snobbishness, bohemian frivolity, the calculations of an accountant, or technical proficiency. It also requires intuition, freedom, objectivity, and non-conformity to any sort of outer criteria such as being liked or not, success or failure, fame or oblivion. And moreover—writing is penetrating into yourself, reaching some kind of second heart and remaining beside it in silence.

I have read and heard statements and conclusions about what writing is. I myself have tried to find some kind of satisfying explanation of the work of a writer. In the end, I realized that however I may try to explain and describe it, I cannot express its essence, but can only circle around it. Just as I cannot cite an idea from some notable writer that I’ve remembered because it succeeded in expressing the secret.

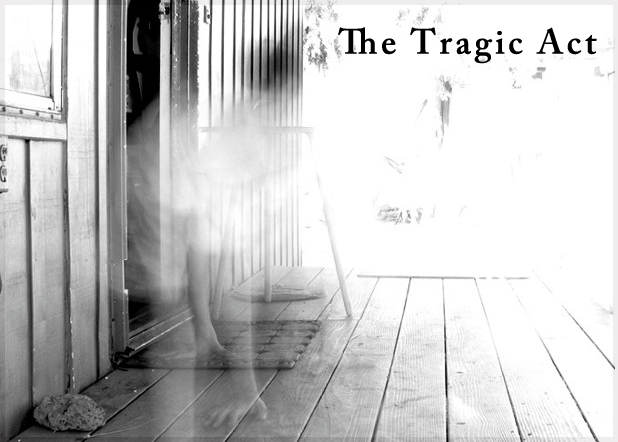

And as often happens in life, I heard the definition of writing that is the truest and most natural one to me in a friendly conversation, uttered quite offhandedly by the poet Boyko Lambovski. We were discussing the work of the young poets who were participating in the Southern Spring competition; we argued, then we agreed; new points of dissention arose, and we overcame them through dialogue. And from time to time, someone would go off on a tangent on points in connection with poetry in general, and the rest of us listened. And so Boyko explained, short and sweet—writing is a tragic act.

Sometimes people utter some insight and they themselves don’t even notice it; I notice this phenomenon not infrequently when the conversation is honest and sincere.

Yes, it is a tragic act. If it isn’t tragic, if it isn’t burning, then it’s better for it not to exist. If it is not a tragic act, the reader will intuitively sense this at once. This doesn’t mean that the result of a tragic act is to write only about the tragic, the dark, the frightening, or the chilling. On the contrary, writing comedy is also a tragic act—love poetry, as well. It is not genre which defines a tragic act, nor again is genre a result of the tragic situation. The tragic comes from the fact that writing is speaking that is born out of silence. Writing begets something that up until this moment has not existed; it is conceived in some kind of secrecy, and its end is uncertain. Its completion is not subordinate to your will. After you begin writing, you are no longer the master, but a servant.

The act of writing is moving in darkness and solitude—you are alone, you cannot turn to anyone for help, you move by feeling your way through a darkness that you cannot come out of; you begin living a parallel life, because you have to both live in the workaday world and at the same time to break away from it as much as possible, living with other people who are real and unreal, the living and ghosts; sometimes you tell them how to act, sometimes they tell you; writing is like traveling in the subway without getting out for months on end. You’re in a tunnel, you hear the monotonous clacking and whistling, but you don’t know in what direction you’re moving, you have no external points of reference, you don’t know when you will step out into the light.

The tragic act is this cry—God, here, look at me, Your insignificant and piteous creation; I am not complete, I am not healed, I am mortal, I am sick from this death, from its inevitability, from fear of it; I am broken, I am in pieces, and I cannot collect all of the pieces and make myself whole, I cannot put things in order—neither myself, nor others, nor the world around me; I am poor, I am insignificant, I am nobody, I am nothing; come, come help me, whisper to me so that I can get this world in order and myself within it, and explain it to myself so that I will not be cast out from the world, and away from others, and away from myself.

You realize that you are approaching something that is intrinsic only to the Creator, you beg Him for forgiveness for having approached this thing that belongs only to Him, but you also beg Him to sustain you because you feel your insignificance before Him; you ask Him questions, but you know that you have to direct your questions inward on yourself. You are waiting for the answer and you continue to write, and you cannot stop anymore.

Throughout this time you cease being you and you do not know whether, in the end, you will be able to be you again. Most often, at the end, you are already someone else.

This tragic act is difficult. An easily written text is always recognizable by its lack of power. A text has power when you have poured your strength into it. The power of your characters is drawn from you. In order to endow them with power, you have to be devoted to them until the end—that’s what Aristotle says in his tract “On the Art of Poetry”: The one who can arouse emotion is the person who is feeling emotion himself, and the person who arouses anger is he who himself most truly feels anger.

But the tragic act is also an act of love. You believe that the Creator will allow you into His Holy Sanctuary. You believe that your characters love you the same way you love them. You believe that the readers of what you have written will come to love your characters the way you have come to love them; you believe that they will lead you towards the Creator who led you before this.

And at the end, after the last point, will joy come? Yes, a joy will set in, in which you do not forget the tragedy in the act of writing. Apart from this, a final point does not exist—in the end is always an ellipsis, loaded with a new tragedy.

—Translated from the Bulgarian by Traci Speed

This craft essay was delivered by the author at the Sozopol Fiction Seminars (June 7-11, 2018), sponsored by the Elizabeth Kostova Foundation.

back read “Andreya” by Teodora Dimova