Spreading across the globe, the coronavirus is reaping a grim harvest from communities of color, the old, the poor, the medically compromised, refugees, essential workers, front-line doctors and nurses, even the healthy. And once-healthy economies. Now it may add democracy to its tally: taking advantage of the pandemic and shelter-at-home restrictions, mainland Chinese rulers are squelching Hong Kong’s thriving democratic culture.

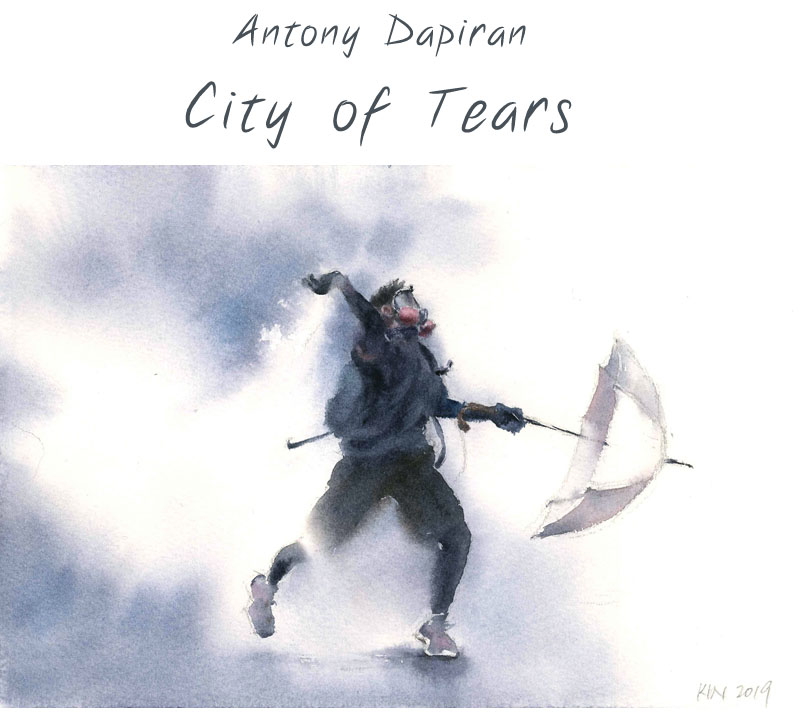

2019 was a year of fearless mass protests by the people of Hong Kong defending their freedom of home rule. “City of Tears,” this Ninth Letter excerpt from Antony Dapiran’s City on Fire: The Fight for Hong Kong, tells the history of this uprising and its stories of stirring bravery. For readers here in the U.S. the accompanying images—in photos and art—of protesting crowds, brutal police tactics, masks, and clouds of tear gas are eerily familiar, as if Hong Kong roils not on the other side of the globe, but right across the street.

—Philip Graham

Tear gas rounds describe a graceful arc as they drop down out of the blue sky, trailing feathery tails of smoke like streamers. The shells hit the road with a ping, and sparks fly as they skip gaily along the asphalt. As they roll to a stop, the shells hiss like an angry snake, dense smoke pouring out of the top of the small aluminum canister, and soon the street is enveloped in clouds.

The most important thing to understand about tear gas is that it is not a gas. It is a substance, a sort of powder, delivered in the form of smoke from a burning tear gas shell. That powder is 2-chlorobenzylidene malononitrile, known as “CS”—a compound developed and tested at the United Kingdom’s notorious Porton Down military facility. As the tear gas canister burns, which it does for around a minute, it spreads smoke containing tiny particles of CS that stick: to clothes, to skin, to surfaces.

If you get caught in a cloud of tear gas, the first thing you feel is a stinging in your eyes—a feeling akin to handling raw chili peppers and then touching your eyes. You will reflexively close them as they begin to stream with tears. Next, you will feel the burning in your nose and throat. You will choke and cough as the tear gas attacks your mucous membranes, and you will be gripped with the sense that you cannot breathe. At the same time, you will feel your skin prickling like a bad case of sunburn. Finally, if you are unlucky enough to get a lungful, you will be overcome with nausea; you will start to gag and spit, perhaps vomit.

But most important, from the deployers’ point of view, will be your psychological reaction to tear gas. Tear gas obliterates the solidarity of the crowd. When you are hit with tear gas, no longer are you a member of a group gathered together with a common purpose. You are alone, your mind blank, all prior thoughts replaced with only one: the need to get away. Eyes closed, coughing, choking, blinded and stumbling, you will run.

As well as having a psychological effect on those being gassed, tear gas also has a psychological effect on those deploying it and those looking on, either in person or through the media. By creating a scene of violence and chaos, tear gas works to objectify the crowd, turning it from a group of human beings into a seething, writhing mass. Tear gas also helps to turn a protest into a riot—and therefore makes it a legitimate target for further state violence.

Understanding this perhaps helps to explain why Hong Kong police deployed so much tear gas on the citizens of the city in the course of 2019, often when the crowd was not violent, not charging police lines—sometimes even when the streets were totally empty. It helped to justify the police’s own actions: ordered to deploy force against the people, tear gassing those people turned them from fellow Hong Kong citizens, with whom they might sympathize, into an objectified other, into criminals.

The physical effects of tear gas wear off fairly quickly. Rinsing out your eyes with water helps, as does a gentle breeze to blow the CS crystals off your skin and clothes. Within half an hour, your breathing will return to normal. But you need to remain vigilant. Tear gas hangs in the air for long after the smoke is no longer visible. If you are wearing protective gear and manage to avoid exposure during the initial burst, but then make the mistake of later touching your clothes and then touching your face, you will inflict the CS upon yourself.

The danger of real physical harm from tear gas comes not from the gas itself, but from the canisters used to distribute it. Tear gas canisters are fired from Federal Riot Guns at a muzzle velocity of around eighty meters per second. That’s less than one-tenth the speed of a regular bullet, but still enough to cause serious injury, especially if the metal canisters—which, with a 40mm diameter, are significantly larger and heavier than a bullet—strike the head or face. The other risk of injury is from burns: tear gas canisters are incendiary devices, and often burst into flame upon hitting the road, sometimes burning hot enough to melt the bitumen.

Shortly before Hong Kong police fire the first rounds of tear gas, they will raise a black banner that reads: “Warning. Tear Smoke.” Sometimes.

Sometimes they will do that. At other times the black banner will be raised shortly after the tear gas is fired, as a kind of afterthought. Sometimes it will not be raised at all. But when they do raise that black banner, it seems almost quaintly polite, like a remnant of Britishness left over from the old colonial police force.

If you are not close enough to see the flag, you can wait further back and listen for when those toward the frontlines call out, “Hak kei!” “Black flag!” Or listen for the crack and pop as the tear gas is fired into the crowd. It sounds almost celebratory—like firecrackers, or a champagne cork—and your instinct may even be to greet it with a cheer.

In the absence of the black flag, a more reliable indication is to watch for when the police put on their own gas masks. In the hot, humid Hong Kong weather, they will only do this when it is absolutely necessary. And when it is necessary for them to put their masks on, you had better make sure you have your mask on too.

American conglomerate 3M makes a variety of equipment that provides protection against tear gas. Hong Kongers are familiar with the various models of 3M personal protective equipment, and can speak about the relative merits of the half-face respirator—probably the most popular model among Hong Kong protesters, easy to don and remove, but only effective if you wear it with proper, non-vented eye goggles, another 3M product—as compared to the full-face respirator—more effective, but less convenient. These respirators have clip-on filters, and Hong Kongers tell you that you will want the multi-gas/vapor cartridges together with the P100 particulate filters, which will help to filter out the CS particles as well as pepper spray. The particulate filters are bright pink in color, a signature feature of Hong Kong protester attire.

On September, 28, 2014, in the event that prompted the beginning of the Umbrella Movement occupation, Hong Kong police fired eighty-seven tear gas shells at the crowds. It was the first time that tear gas had been used against Hong Kong people in almost fifty years, and it would be the only occasion in the course of those protests on which tear gas was used, such was the public outrage it provoked.

On June 12, 2019, the first occasion on which police fired tear gas during that year’s protests, they fired over fifty rounds. During the day that saw the siege of Chinese University in November, police fired over 2,330 rounds in the course of a single day, approaching two rounds for every single minute of the day.

By the end of 2019, over the course of seven months of protests, Hong Kong police had fired over 16,000 rounds of tear gas onto the streets of Hong Kong.

Hong Kongers have a way to describe those days when the police unleash round after round of tear gas on Hong Kong’s districts. They call it an “all-you-can-eat tear gas buffet.”

Tear gas is a chemical weapon, first used in World War I to flush troops out of the trenches. As the world came to understand the horror of chemical warfare, tear gas, along with other chemical weapons, was banned under the Geneva Protocol of 1925. However, its use was permitted for domestic law enforcement, a position that remains under the more recent Chemical Weapons Convention of 1993.

In the colonies—places such as India, Palestine, and colonies in Africa—the British turned to tear gas to avoid using lethal force against local populations, and to preserve their reputation as “benevolent” colonizers.

And if the Hong Kong Police Force’s “Warning. Tear Smoke” banner seems like some quaint colonial vestige, that’s because it is. In the 1930s, as the British government’s Colonial Office and the War Office grappled with how to reconcile the use of tear gas on civilian populations when it was banned for use in war, the War Office felt the position could be justified by “a declared intention to use tear gas and adequate warning given to opponents”—thus the black flag was born, and with it, in British minds, the morally justifiable path to the use of tear gas on civilian populations in the colonies. It was also the British who insisted on using the term “tear smoke” rather than “tear gas,” the latter being felt to be a “much more alarming term” rather too suggestive of the poison gas attacks of World War I.

However, it was some time before the British government became comfortable using tear gas on British soil. Tear gas was used on British civilians for the first time at the start of the Northern Ireland Troubles, when the Royal Ulster Constabulary fired tear gas in the Battle of Bogside in August 1969, deploying over 1,000 rounds over the course of two days.

The controversy surrounding the use of tear gas in the Bogside prompted an independent enquiry, the Himsworth enquiry, into the possible toxic effects of CS gas. The Himsworth report concluded that CS gas was safe within certain prescribed dosage levels, and the report has since been used to justify the use of tear gas against civilian populations across the globe. That justification, observed Anna Feigenbaum, the author of a book on the subject of tear gas, is based on the assumption that “protesters are always supposed to be able to get away from the smoke, and the smoke is always supposed to be able to evaporate and be ephemeral. The problem,” she added, “is that in Hong Kong neither of those things is true.”

Hong Kong’s streets are narrow and congested. When tear gas is fired, it hangs in the stagnant passages between the buildings in the humid, subtropical air. The people, trapped on streets that are challenging to navigate even under normal conditions, find their escape blocked by protester barricades—built to slow the advance of police—and by police cordons and check lines. Police have also fired tear gas into dangerous locations such as bridges and walkways, and inside subway stations. Tear gas has been fired in Hong Kong’s residential areas—the most densely populated in the world—with canisters landing on balconies, outside the windows of aged-care facilities, and even inside people’s homes. Families, the elderly, and children have all been affected, innocent victims of the clouds of gas unleashed upon the city, exposing them to higher concentrations and over periods of time far greater than was contemplated by those studies that consider tear gas to be “safe.”

As the 2019 protests unfolded in Hong Kong, the world’s leading medical journal, The Lancet, published a letter from a group of Hong Kong medical academics complaining of a lack of government attention to the health effects of tear gas and a failure to advise the public on how to protect their health and decontaminate their surroundings.

It has been estimated that hundreds of people around the world have died as a result of the use of tear gas or its effects. Medical researchers conducting a systematic review of injuries and deaths caused by tear gas and other chemical irritants observed that the use of tear gas can undermine freedoms of expression and peaceful assembly, “by causing injuries, intimidating communities, and leading to escalations in violence on all sides.” They concluded: “Although chemical weapons may have a limited role in crowd control…they have significant potential for misuse, leading to unnecessary morbidity and mortality.”

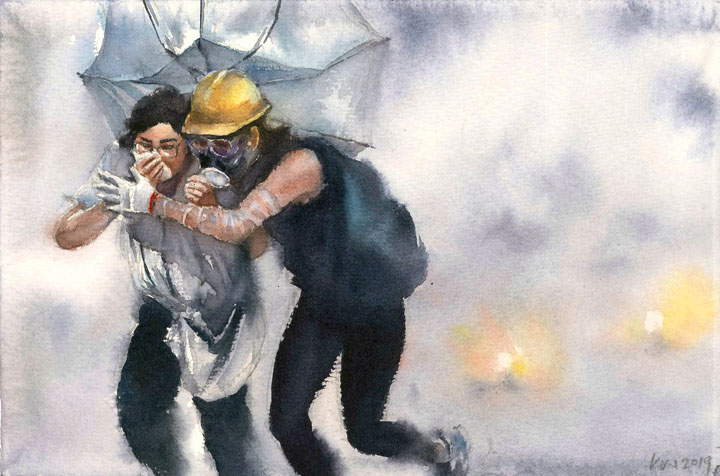

Just as the physiological effects of tear gas wear off fairly quickly, so too do the psychological effects. The crowd, once it loses its fear of tear gas, comes back more determined than ever. Tear gas teaches resilience—and resistance. Hong Kong protesters became so adept at resisting and countering tear gas that it quickly lost its effect as a “force multiplier.” Instead, the Hong Kong protesters just donned their gas masks and goggles, picked up their umbrellas, and fearlessly stood their ground.

Yet the tear gas kept coming, in amounts such that it went far beyond its intended purpose, to disperse a crowd, and became a punitive measure, an offensive weapon, used not to de-escalate but to punish.

Writer Simon Winchester, in his book In Holy Terror: Reporting the Ulster Troubles, wrote about the effect tear gas has on crowds in 1970s Northern Ireland. Its deployment by the British army, he said, turned “what had been a tenuously bonded…mob of hooligans and housewives” into ‘”a choking, screaming, radicalised and almost totally solid political group.” Tear gas, Winchester wrote, had, “enormous power to weld a crowd together in common sympathy and common hatred for the men who gassed them.”

The same effect was seen in Hong Kong in the protests of 2019. I have watched as wave after wave of tear gas was unleashed upon crowds of protesters. The crowd would break and disperse momentarily, and then, as the tear gas started to dissipate, they would reform, chanting as they advanced again on the police lines, “Heung gong jan, gaa jau!”: “Go, Hong Kongers!”

The experience—and spectacle—of tear gas came to define life in Hong Kong in 2019, whether fighting it at the front lines, choking on it, planning one’s journeys to avoid it, watching images of it billowing on television screens, or just talking about it. Children in Hong Kong playgrounds played “police and protesters,” and talked about tear gas as casually as children elsewhere might talk about sports or computer games.

After the protests of 2019, Hong Kongers have a new saying, and a new aspect to their identity: “You’re not a real Hong Konger if you haven’t tasted tear gas.”

Photos by Antony Dapiran, and watercolors by Fung Kin Fan.

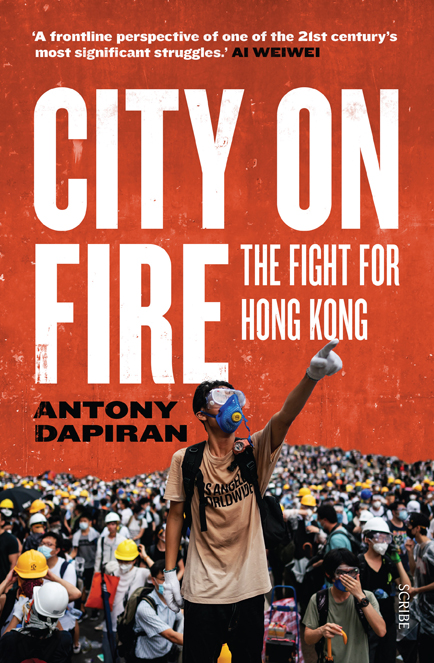

Antony Dapiran is a Hong Kong-based writer. This piece is adapted from his book, City on Fire: The Fight for Hong Kong, published in June in the US by Scribe Publications. Interested readers can subscribe to his newsletter about the latest political developments in Hong Kong here: antd.substack.com. He tweets at @antd.

Antony Dapiran is a Hong Kong-based writer. This piece is adapted from his book, City on Fire: The Fight for Hong Kong, published in June in the US by Scribe Publications. Interested readers can subscribe to his newsletter about the latest political developments in Hong Kong here: antd.substack.com. He tweets at @antd.

Interior designer by day; watercolor enthusiast by night—Fung Kin Fan has been creating his works with watercolor based on his daily experience. He has documented various touching moments of the HK movement for the last year and hopes to encourage fellow Hong Kongers during this difficult time. He finds that watercolor can best represent the nature of the movement, and echoes the slogan “Be Water” at the same time. https://www.facebook.com/fung.k.fan

Interior designer by day; watercolor enthusiast by night—Fung Kin Fan has been creating his works with watercolor based on his daily experience. He has documented various touching moments of the HK movement for the last year and hopes to encourage fellow Hong Kongers during this difficult time. He finds that watercolor can best represent the nature of the movement, and echoes the slogan “Be Water” at the same time. https://www.facebook.com/fung.k.fan