Rebecca Weber

I the Butter Cow Lady

Norma Lyon, a uniquely Midwestern artist who gained wide renown for her incredible life-size sculptures in butter (most famously the Butter Cow), died on June 26, 2011, at the age of 81. In her honor, we’re posting a reprint of Rebecca Weber’s essay “I the Butter Cow Lady,” which first appeared in Where We’re At section of the Fall/Winter 2004 issue of Ninth Letter.

***

Butter sculpting is not new a new phenomenon (it dates back a century in the United States and much earlier among Tibetan Buddhists). It’s not limited to the Midwest (it’s big in Pennsylvania, and Canada featured a very clever butter sculpture: a giant piece of toast). It even isn’t limited to state fairs and agricultural showcases.

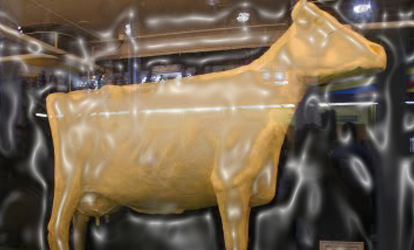

The center of butter sculpting, however, is the Midwestern state fair, and for butter sculpture purists, the Iowa State Fair is the center of the universe. For these believers–as their bumper stickers will attest–Norma “Duffy” Lyon is The Butter Cow Lady.

Lyon, a dairy farmer with a degree in Animal Science from Iowa State, has created butter cows since 1960. She can sculpt six different dairy breeds from memory, and she can finish a full-sized butter cow in about twenty-four working hours. Bored with sculpting only cows, Lyon adds various butter creations to her annual display. Among other things, she has created full-sized sculptures of Garth Brooks, John Wayne, and the Peanuts Gang. Her sculpture of Butter Elvis grew into legend, with people on CB radio and the Internet boasting the healing powers of Butter Elvis. Butter Elvis is said to have cured broken bones, blindness, tuberculoses, and baldness. According to lore, in his brief run Butter Elvis also removed tattoos, grew arms where there were none, changed breast implants into breasts, caused spontaneous orgasm, impregnated women, supplied onlookers with fried peanut butter and banana sandwiches, raised the dead, granted the ability to multiply fractions, and supplied a Japanese tourist with instantaneous fluent English, a green card in his wallet, and the ability to impersonate Elvis flawlessly.

Following the success of Butter Elvis, Lyon challenged herself with her largest sculpture, a full ton depiction of the Last Supper. Last year, she took on a Harley Davison motorcycle to commemorate Harley’s 100th anniversary, her most detailed sculpture to date. Lyon’s specialty sculpture for 2004 is a three-tiered birthday cake commemorating the Sesquicentennial of the Iowa State Fair.

Of all butter sculptors, Lyon is by far the most famous. She’s visited Letterman and is the subject of a GED reading readiness section (“The author’s attitude towards Duffy Lyon is: A. cynical. B. respectful. C. angry. or D. joking”). She is also the subject of a book: The Butter Cow Lady by B. Green (free “I heart the Butter Cow Lady” bumper sticker with purchase).

Lyon, 74, has scaled back production in recent years, following a stroke. Once supplying butter sculptures to fairs in thirteen states and Canada, she’s shifted her focus closer to her Toledo, Iowa home. Her retreat from widespread sculpting work, coupled with the 1999 retirement of Dan Ross from his thirty-six year run as the sculptor at the Ohio State Fair (where he created cows, Neil Armstrong, and Darth Vader for an estimated 18 million viewers), has opened the door for new talent. Pennsylvania native Jim Victor fills in, taking his talent on the road to about eleven fairs and festivals per year. In Ross’s absence, Ohio hires a team of sculptures to create yearly displays, including one of the Wright brothers. After featuring Duffy Lyon’s butter cows for decades, the Illinois State Fair hired Nancy Hise, a Wisconsin native specializing in cheese carving, to take over butter cow production. A press release from the Illinois State Fair announcing Hise’s arrival dubbed her the new Butter Cow Lady. Perhaps in response, the Iowa State Fair homepage now claims that it features Butter Cow Lady Duffy Lyon and her “never duplicated” butter cow.

Any hints of rivalry aside, butter sculpting is an odd activity to have become a tradition, especially in the often-practical Midwest. Spending hours of work and literal tons of butter on temporary sculptures is an indulgent activity, one that perhaps only fits within fair culture. Fairs center around indulgence. Pay five dollars for a carnival ride? Eat deep fried Oreos, Twinkies, and Snickers bars? Sure, because the fair comes but once a year. It will probably return, but in a slightly different form, with different deep fried foods and with a different runner-up from “American Idol” performing on the grandstand. It never lasts.

When it comes down to it, Midwestern butter sculpture varies little from the ancient tradition of Tibetan Buddhist butter sculpture. The materials and scale are vastly different. Buddhists use colored yak butter mixed with candles and fat to make it stand up to warm conditions, and they usually form intricate, colored patterns, as in sand mandalas. Midwesterners use a half ton, give or take, of low-moisture, pure cream dairy butter to create life-sized golden statues and defeat August heat with giant refrigerated display cases that create a world of forty-two degrees.

The process and result, however, remain the same. In both situations, the sculptor creates detailed symbols of life in painstaking processes. Sculptors craft the objects with full knowledge of the sculpture’s fate: the Buddhists destroy their sculptures upon completion or soon afterward, demonstrating the concept of impermanence. With the rare exception of the Minnesota Butter Heads, which are given to each of the young women of the fair court immortalized in butter to do with as they wish, State Fair butter sculptures last the run of the fair, usually eleven days. After that, the golden calves and other gods, false or true, are allowed to thaw. Workers pack the softened butter into buckets and send it to freezers to live out the year, to wait for reincarnation. The butter can stand up to four sculpting processes before it loses its pliability from age and overwork. Today’s Garth Brooks brings next year’s Butter Elvis, a circle of life not unlike that of butter and its traditional sculpture: as butter comes from cow, so cow comes from butter.

–Rebecca Weber