Ivayla Alexandrova

an excerpt from

Ardent Red

a documentary novel

Having lost the coveted territory of Macedonia in the Balkin Wars of 1912 and 1913, Bulgaria joined the German-Austrian side in World War I, calculating the eventual return of Macedonia. Having fought on the losing side, however, Bulgaria lost further territory, and this was one of the reasons to join in an alliance with Germany in World War II. Though initially allied with Germany, Bulgarians successfully refused to deport their Jewish population, with public protests and Orthodox priests threatening to lie on railroad tracks to stop any transport trains. In 1944 Bulgaria declared war on Germany, but days later, on the 6th of September of 1944, the Soviet Red Army invaded, and after this date Bulgaria became a part of the Soviet sphere of influence. In the purges that followed, thousands were condemned to death or imprisoned.

One of those victims was the writer, artist and journalist Rayko Alexiev. This is the story of his last days, uncovered after nearly a decade of investigation by the writer Ivayla Alexandrova.

9th of June 1994

Wednesday

Three o’clock in the afternoon.

The window is half open.

It’s warm, suffocatingly warm. The air is sticking to our bodies, damp and unpleasant, so sticky that we could smear it on ourselves. The afternoon is pulsating slowly in our brains. The clock on the wall, the claxons of the cars, the rumble of the ships in the river, everything dissolves into a hot bouillon of indefinite sounds and vague images, and the two of us, Madame A. and I, sink in it.

We pretend to talk. It’s not a dialogue though, but an endless monologue of Madame A., she is speaking out whatever passes through her mind. Maybe that’s her way to ease her conscience, or at least to trick it. She desires that I describe all of her stories (but I’m not that kind of person).

“I wanted to become an actress and told it to my uncle Kossio Kissimov, who already had a career at the National Theater. We got along really well. ‘Don’t worry,’ he comforted me, ‘there will be an open call soon, the director Massalitinov will make a Master class. We won’t tell anyone and I will help you to prepare,’ he promised. ‘If they accept you, I will do everything possible to convince your father to let you do it.’ In the end, not much of convincing was needed. I remember that I recited a poem, I can’t really recollect the title, but when I finished, the chief playwright of the National Theater, Yordan Badev, came on stage and told me: ‘I’m happy to meet the future Sarah Bernhardt of Bulgaria.’”

Madame A. is exaggerating, but this is forgivable. Everyone has the right to convince themselves of their past talents, especially if they were left unrealized…

“When the Master class came to an end, six persons were selected as trainees at the National Theater and I was among them. I had three leading roles in a year – in Squaring the Circle, by Valentin Kataev, in The Camel through the Needle’s Eye, by František Langer and The Letter, by Somerset Maugham.

Madame A. on the stage of the National Theater, 1931

“All of a sudden, an announcement appeared one morning on the black board in the theater stating that on Friday morning at 10, the writer, artist and satirist Rayko Alexiev would meet the new generation of actors from the class of Massalitinov in Hall number 6. No one knew why he wished to visit us, but the very news that Rayko Alexiev was coming to visit was enough. The old staff came with low-cut necklines, all the actresses ran to bleach their hair and covered themselves with fake jewels as if they were Christmas trees. They knew that he had big ideas and decided that even though he came to meet the young ones, the old ones could get something out of it too.

“I also went there. But I thought that going with a low-necked dress and cologne at 10 a.m. was a bit overdone. This didn’t seem chic to me, so I limited myself to a white shirt and a blue school style skirt. And then, the actor Kosta Raynov and I hid behind a door, so that we wouldn’t attract too much attention.

“Rayko Alexiev came with Yordan Badev and two or three theater directors. He greeted everyone and made a short, but impressive speech saying that Bulgaria had lost the First World War, it had lost territories, but it was up to its talented people to show that not everything was lost. He spoke well and he received applause. Afterwards, he and Badev met with the public. Rayko got acquainted with everyone from the Master class and then suddenly Badev asked if someone had seen Ms. Grancharova (Grancharova is my maiden name). They said that they noticed me around and, since I heard my name, I had no choice—I had to peep behind the door. Badev took me by the hand and said: ‘Ms. Grancharova, Mr. Alexiev would like to meet you. He saw you in The Letter and was very impressed.’

Madame A. pauses. “I had played a Chinese woman of easy virtue working in a café-chantant. An English official of high rank falls in love with her so badly that he’s ready to kill his wife in order to marry the Chinese woman. When my uncle Kossio had heard of the role I was given, he reacted: ‘Does it occur to Yordan Badev that you haven’t been in a bar yet?’ So he ordered a green satin dress for me, it was sleeveless, with a low-cut neckline and a tight-high split—everything was visible when I danced…”

I look at Madame A. furtively and involuntarily: she continues to think that she is beautiful. The white silk nightgown seems loose under the reseda robe—ages ago it hid a vigorous body, a body now dried out by the passing of time. Ironically, the only features that still look chiseled and tangible are her legs—back then popping out of the split of her dress and today popping out of her slippers.

“You know,”she smiles, “once a photographer, a friend of my father, asked me to pose for him for postcards and he said: ‘We could capture just the legs of the young lady and leave out the head, she would be less embarrassed…’ I expressed my indignation right away—‘Oh, sir, am I just a pair of legs?’”

Fixing the moment of eternal youthfulness—apparently this really pleases her.

“So my uncle took me to Parisiana, the most famous bar for women of easy virtue in Sofia at the time,” Madame A. continues, “so that I could see how they behaved. And I attracted instantly the attention of some… well-cultivated men, who invited me to dance. And as I refused each time, a tipsy Casanova almost got to fight with my uncle, mistaken that he was keeping me for himself.

“We went there twice more and then I decided that I had observed enough for my role in The Letter.

“So when I gave my hand to Rayko when we were introduced that morning, he looked startled. He took a look to Badev, and then back to me and said: ‘Listen Yordan, there is something that I don’t get here. I saw this actress embodying a prostitute perfectly, as if she had been born in a café-chantant, and now you introduce me to this child and you pretend that this is the actress. Who is the actress and who is Vessela?’”

She makes a long pause, obviously playing at indifference. Then she sighs heavily and closes her eyes.

“We got married in the church Sveti Sedmochislenitsi in Sofia. It was the spring of 1932, on a Saturday, Rayko was 39 years old. What an event: Rayko Alexiev is getting married and Nikola Mushanov, the Prime Minister at the time, is the witness. All the newspapers buzzed about the wedding, Nikola Mushanov was a great admirer of Rayko’s art. They were old friends and Mushanov was so full of respect for Rayko that he called him ‘my elder brother.’ After our marriage, our first visit as newlyweds was to our witnesses…”

Madame A. interrupts her own talk from time to time, asking me, “Are you listening?”

Leaning on the soft chair, I am listening. I have my doubts about one, or even two stories, but these doubts mingle with confirmations.

She has repeated the same stories in front of others.

*

Later, I would see with my own eyes Madame A.’s strict depiction of her life in the Archive of the Ministry of Interior. She doesn’t beat around the bush in this text (or rather, this testimony, given during an interrogation led by inspector Zeev director of the Investigation Department of the State Security).

After the 9th September 1944, my husband [Rayko Alexiev] was arrested by the militia in Sofia. Following his arrest, the apartment that we rented at 33 Tzar Osvoboditel boulevard, was opened forcibly and two officers remained on guard. Upon my arrival in Sofia, I tried to enter our home, we had left our clothes, bed covers and bed sheets there during the evacuation. The officers didn’t let me in, saying that I should contact the Ministry of Interior.

[O]n the 18th of November my husband passed away. I visited Mr. Georgiev again, begging him to let me take a dark suit from our apartment, so that we could bury my husband with it. Unfortunately, I found out that all of his clothes were missing. A week after his death, an acquaintance told me that she saw our furniture being taken out with trucks…

Vessela Alexieva

Truth then shone on the tip of Madame A.’s pen as she listed the thieves’names: this was taken by that person, and that was taken by.

As for me, I would put together the pieces of stories (or the pieces of paper) as if I was creating a living creature.

It’s relatively simple. It cost me about nine years, spent in libraries and archives. Sometimes the pieces didn’t follow an order: suddenly there popped up a fact which had nothing to do with the rest. Later it turned out that it was not arbitrary. Everything formed a chain, an endless chain, as if it was a part of a bigger plan. What I did was merely follow this chain, as a hypnotized bird.

What did I feel? Mostly terror.

While writing this book, I lost my mother.

She was ill for three and a half years. And since her friends and relatives didn’t visit her, by the time she was dead, she was already forgotten. She had a brain aneurism first, then dementia blocked her mind, she started calling my daughter Sani “Mite” and called me, “You, me and you.” At the end she fused all her fears and desires into a single phrase: “Please, cover me with a piece of bread.”

She was about to die four times. And four times she came back. People told me: “It’s because she wants to live so much.” I thought that it was because she didn’t believe in God and didn’t ask for help. One day the poet Malina Tomova told me “You talk too much about her suffering, and that’s why she suffers…” And she was right, after her death the pain sealed my lips.

But it opened my eyes to the calm tone with which Madame A. addressed her personal wounds: “Come on, who’s afraid of death? One ought to be afraid of life, not of death…”

*

During my first meeting in 1991 with Madame A., Yulia Petrova, a journalist and a colleague who had accompanied me, asked her, “When did you sense for the first time the borderline between the two epochs, the moment when something disappears and something else, frightening, replaces it?”

The border turned out to be quite palpable:

“Well,” Madame A. replied, “Rayko Alexiev went on publishing his newspaper during our evacuation in Chamkoria, he was putting together Cricket and each Friday and Saturday he went to get it printed in Sofia. He insisted that I accompany him. During one of our trips to Sofia, on the road to Samokov, we met a group of German soldiers. They were impeccably dressed, clean, well shaven, their hair trimmed short. Marching cheerfully, playing harmonicas and accordions. Suddenly, I started crying without uttering a word. Rayko couldn’t get it. We arrived in Sofia, but I continued sobbing. I was given something soothing at the pharmacy near our flat, my husband took care of me – we ate something, he tried to distract me, but kept asking from time to time for the reason of my grief. ‘I don’t know,” I said in the end, ‘I have the feeling that something is about to leave us forever, that the sky is not so blue anymore and the streets are full of gloom.’ ‘You are fantasizing!’ said Rayko. Alas, I wasn’t. It was August 1944.

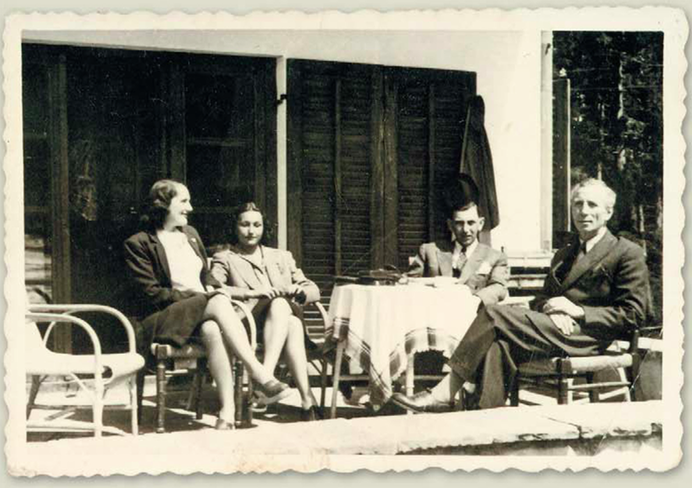

The last summer before the Soviet invasion, 1944

“We went back to Chamkoria and there, after I gave the situation a thought, I related everything to this group of departing German soldiers. And somehow, I understood that this marked the end of our beautiful and free life. My husband was never into politics, he was a writer, an artist, a cartoonist. It happened indeed that he gave advice on what he considered useful and good for the country, but he was never a political activist. I was not afraid that he would lose his position when the Germans left, that we would be hungry. I was afraid that freedom, tranquility and security would come to an end.

“Everyone in Chamkoria started packing and preparing to leave. However strange it might seem, at first I didn’t connect that to the wartime situation in the country. But friends, mainly foreigners and diplomats, kept coming home saying: ‘Hurry up! The last echelons leave soon, it will be terrible!’ ‘Why do I need to run away,’ Rayko wondered. ‘I never did anything bad to anyone. I always took the side of the weak. I love Bulgaria! I can’t become an emigrant begging with a small bowl! I’ve always paid my taxes, I don’t have a single cent in a foreign bank. A country house and one or two lots, that’s everything I own after a life full of hard work!’

“Rayko was creating every single page of the newspaper all alone. He was looking for people who could help him, though, in order to find a bit of relief and freedom to spend more time with his family, with his kids, he loved playing and having walks with them. He could have left the country very easily, but he was suffering from a terrible love for Bulgaria. He thought that his work was only possible in Bulgaria. He wasn’t creating cartoons to criticize ministers out of personal hate or pleasure. Rayko truly wanted the people of Bulgaria to be happy and to evolve.

“Finally, when he figured out how anxious I was for the kids and for myself, he got to the point of saying: ‘I won’t leave. I’m not a rat that flees the sinking ship. But if you wish, you can have the car, take the kids and go.’ It is true that I was very young then, with three small kids, but I told him: ‘If you stay, I stay too!’”

Now, when I remind Madame A. of this previous conversation of ours, her lips start to tremble and fill with wrinkles.

I don’t know what to do. I ask uneasily, “I’ve heard, I’ve read: ‘Rayko Alexiev died in peace in 1944.’ Could we call what happened with Rayko Alexiev ‘dying in peace’?”

She smiles in return.

“No, he was beaten to death…

“I don’t know, maybe I should start with the night in September when the Red Army crossed the Danube River and came into Bulgaria under the pretense of helping the Bulgarian people, of saving them from the fascists. Everyone knows that this had nothing to do with the well-being of the people…”

*

In the memories of the Prime Minister Nikola Mushanov:

“If we had managed to sign a truce with England and the US – to whom we ‘symbolically declared war’ in 1941—there wouldn’t have been any reason for a foreign invasion in our territory. On the 5th of September we had already put our diplomatic relations with Germany to an end upon our own initiative. On the 6th of September I told the Russian representative Yakovlev that the war with Germany had already been settled, but that it would be announced with a 48-hour delay upon the request of the Minister of war, General Marinov. However, on the very same evening, the Soviet Union sped up their plans and declared war on Bulgaria. They did it as they needed a pretext to invade not only our country, but the entire Balkan Peninsula. As I said in court: ‘The Great powers have plans which often surpass our own and they do things which, though formally related to the political conduct of small countries, are in fact motivated by quite different reasons, which don’t have much to do with these small countries—everything would have been done that way, even if our demeanor had been completely different.’ I had a very interesting conversation with the Russian diplomat Kirsanov a short time before the crash, on the way the momentary needs of Russia could influence and change completely its attitude to certain political figures. I said to Kirsanov: ‘What exactly do you expect from us? Do you really want to create the impression that we are an obedient, voiceless satellite of yours which follows you blindly, even when it is against the Bulgarian interest? What would be the use of such allies—politicians without a face? ‘Listen,’ said Kirsanov, ‘we are realpoliticians. For us it doesn’t matter what you did earlier, what were your services to us in the past. What is important is whether now, in this particular moment, you could be of any use to us or not, and this determines our behavior.’”

*

“When the Reds invaded,” continued Madame A., “we were still in Chamkoria, while everyone else had left. Ten days after the 9th of September invasion Rayko decided that we would leave for Sofia too. But there was a problem – a bomb had hit the street of ‘San Stefano’ where our apartment block was and it had broken all the windows. ‘I’ll go first and repair the windows, and only then you would join me,’ said Rayko. I gave him a box containing all my jewels – both the ones I inherited and the ones Rayko gave me as presents and I asked him to bring it to my father, as our apartment was not a safe place anymore.

“There was a pastry café called ‘Tzar Osvoboditel’, at the corner opposite the Military Club in Sofia, all the writers and artists used to gather there. This was the intellectual centre of Sofia and of course, Rayko went straight there after getting off the bus. I didn’t witness what followed, but I will tell you what I’ve heard and what I’ve read later. Lev Glavintchev, the director of the Militia at the State Security at the time, entered this pastry café and arrested my husband. Everyone jumped in his defense: ‘What do you think you’re doing?’ they said, ‘This is Rayko Alexiev! Where are you taking him?’ ‘Shut your mouths,’ snarled Glavintchev, ‘or else I’ll drag you out with me!’”

Last photo of Rayko Alexiev

*

In his book Diary, the literary critic Boris Deltchev points to the involvement of the Bulgarian writer Krum Kiuliavkov:

Ivan Bogdanov told me about the arrest and the death of Rayko Alexiev while having a coffee at ‘Kristal Café’ in Sofia. Krum Kiuliavkov was the one fully responsible. Alexiev was arrested and tortured on his order. His death came as a consequence of physical torture. What’s more—Kiuliavkov appropriated certain of his household belongings, mainly some expensive pieces of furniture. Bogdanov explained all that with his personal resentment: Kiuliavkov had supposedly contributed to the newspaper Cricket, but later (all this happening during the war) his access to the newspaper was denied.

Further in the text Deltchev testifies in his own name:

After the 9th of September Kiuliavkov held an important position at the Direction of Militia, he was head of the sector responsible for the artistic intelligentsia. So the measures against Rayko Alexiev were fully his decision (there are some traces of a confession about this in my memory). Whether the tortures were also done under his request or the repressive machine simply kept turning, led by other forces—this I can’t say. Profiting from his powerful position, Kiuliavkov appropriated a spacious home at Slavianska street, and then went on a hunt for furniture and household items, without any scruples. This happened partly in front of my eyes. Therefore, I find it more than probable that he appropriated also some pieces of furniture from the home of Rayko Alexiev…

The motivation of Kiuliavkov’s actions seems to be psychological and not logical, working under a different mechanism, similar to the definition of the philosopher Assen Ignatov: “communism is a manifestation of the death drive.”

The death certificate of Rayko Alexiev was issued by the Red Cross. According to it, he died of an ulcer. This doesn’t put an end to his story though. In an interview with Albert Benbassat in 1991, Rayko’s son Vesselin Alexiev offered detail:

It is known that one of the main torturers was the investigator Zeev, famous for his sadistic methods. In the hospital of the Red Cross, Professor Tashev made a great effort to save my father, he gave him several blood transfusions and his condition improved significantly. Then the professor called my mother and told her that Rayko Alexiev would be saved. According to his words, he already started making jokes: ‘Doctor, I don’t need a restricted diet, I need a pork steak and a glass of wine and I will get better without a delay…’ After several round-the-clock shifts, Professor Tashev went home and left my father alone with a physician (or a partisan, no one knows what she really was), who told him that she would give him an injection that would make him feel better. Immediately after receiving the injection Rayko Alexiev died.

I have the text of his prison sentence. It states that he damaged Anglo-American prestige with two cartoons and one topical poem. Nothing is mentioned of the USSR, even though it is possible that the NKVD contributed to his liquidation. Because in 1937 he made a cartoon of Stalin—he’s portrayed with his pipe, and above his head there is a red star, a severed head upon each of its rays – Trotsky, Bukharin, Zinoviev… The text below reads: ‘Don’t hurry, go one by one, there is a place for everybody.’ And it’s widely known that Stalin didn’t forgive a thing.

Cartoon of Stalin by Rayko Alexiev, in Cricket, 1936: “Don’t push yourselves, there is a place for everyone!”

Here is the end of Rayko Alexiev’s story, according to his son:

My mother managed to demand the coffin with the body and it was brought at home. It was fixed with nails and it was strictly forbidden to open it, but my grandfather ordered that we do it—to check if it was really him inside. We opened the coffin and I couldn’t recognize my father who went to prison just two months earlier. There lay a different person—bloated, unrecognizable, a person who went through great physical and emotional suffering. My uncle, who managed to enter the morgue and to see him nude, said: ‘The traces of beating were visible on his body, the heels of the boots. His genitals were smashed.’

*

Madame A. waves her hand as if to wave time aside. Then she continues speaking fast, gaining strength.

“I stayed in Chamkoria, with my three children and a cousin of mine who used to live with me, a cook and one servant. I felt totally blocked—I had no news whatsoever from my husband, the phone didn’t work, I couldn’t leave the kids alone. And suddenly I heard a tumult, the whole earth was shaking, and I was so terrified, I thought that the Russians were coming and that we were all alone in Chamkoria! What could I do? It was a very cold September night, we took the kids, wrapped them in blankets and we hid in the forest. We spent the entire night hiding there. In the morning the noise was over and we went back. Then we heard from the woman who brought us milk that in fact these were Bulgarian troops who lost their way while coming back from the Aegean Sea.

“In the late afternoon my father—he was seventy years old at the time—came on foot from Samokov, as there were no buses. He heard that Rayko had been arrested. He gathered warm clothes and went to Sofia to search for him.

“Then I decided that we would all go. I organized a taxi. And I found out very soon that Rayko was being kept in the School for the Blind. It was terrifying, it seemed as if every single man had been arrested, because in front of every Ministry, in front of every building, one saw only women, tons of women. The kids were screaming, the mothers were trying to calm them and continued waiting, it was such a tragedy. And so I went to look for connections, for friends and acquaintances. People who had fawned upon us so that they could get invited at our home, where they could meet ministers or even the Prime Minister, now pretended to not know me. The writer Dimo Syarov was one of them, and Krum Kiuliavkov, who had been at home at least fifty times, eating and drinking at our table. Later, when my husband was already dead, I saw Kiuliavkov in the street, wearing my Rayko’s leather jacket.

“And the painter Stoyan Sotirov! Stoyan Sotirov was connected to the group of paratroopers who in 1941 were dropped by the Soviet Union in the aim of doing a coup d’état in Bulgaria, but they got caught. Sotirov managed to flee and ran immediately to Rayko who, full of compassion, gave him the key from our villa and brought him food. When the time of the trial came, Rayko testified for Sotirov, claiming that he was the greatest patriot ever born, and that’s how he managed to keep out of jail. So I went to this Sotirov and I said: ‘You know what happened to my husband, he was arrested and we have no contact with him. I’m very worried and I beg you to do everything possible to get Rayko out of jail.’ And he started twisting, full of fear: ‘Mme Alexieva, I’m very sorry, I can’t help you with anything. We are forbidden from interceding for anybody. Try to contact someone from the Agrarian Party, they don’t follow such strict orders…’

Apparently this story has been haunting Madame A. for a long time. It is erupting, one sentence after the next. She goes on:

“Anyway. We understood that Rayko was in the School for the Blind, but they didn’t let us bring anything to him, we had no chance for any close contact. Until one evening, some guy came home and said: ‘I’m a guard in the School for the Blind, Mr Alexiev was heavily beaten the other night and he keeps vomiting blood, please do something!’

I rushed immediately to Todor Pavlov, he was a regent at that time. I knew that he appreciated Rayko and that he was a good person. I said: ‘Rayko was beaten black and blue, there is no doctor at the School for the Blind, he’s vomiting blood, he will die like that…’ Todor Pavlov called his secretary and told him: ‘Go to this and that hospital and ask for medication to help stop the blood, ask that they send someone to examine Rayko Alexiev!’”

The voice of Madame A. sounds strange in the silence surrounding us, it seems to reach me like an echo, falling apart:

“Meanwhile, the Patriotic War against our former allies, the Germans, had started. The hospitals were full of wounded soldiers, there were no beds for the civilians, and even less for ‘dirty bastards’ like Rayko Alexiev. And when I ran from one hospital to the next in the morning, some refused to talk with me altogether and others chased me away: ‘So what, someone is vomiting blood! Look around, it’s full of wounded people here…’

“Finally I found Professor Tasho Tashev, the director of the Red Cross. He asked me why I came to him, I told him my story and we went together to the Red Cross. Then I had the courage to ask the doctor for a white uniform, so that I could enter the School and see my husband.

“We reached the School and we entered an enormous room, there were maybe thirty or thirty-five people lying on the floor, all dirty, bearded and shabby. I looked around for Rayko and I couldn’t see him. He raised his hand from a corner and when I came closer I recognized him—his hair went white, he used to have very nice hair and now he was as yellow as a corpse. I told him that we came to take him to the hospital, that he would get treated and that he would be fine. He kept making signs that I should keep silent. When we got to the ambulance, I asked him who did that to him and what exactly happened. ‘Very bad,’ he managed to murmur, ‘very bad.’

“Some scribbler or cartoonist once sent his work to Rayko, asking to get it published in the newspaper. But Rayko didn’t publish it. When the time came that this person stood in front of him with a submachine gun and said, ‘You bastard, you scoundrel from Sofia, you didn’t want to publish me, but can you see the gun now?’ Rayko had answered: ‘You can have four guns if you wish, but that won’t make you a cartoonist, nor a humorist. I would have been happy to see a bit of talent. But apparently there was nothing in your scribblings, nothing that I would offer to my public…’

“Witnesses told me how this guy went jumping with his boots all over Rayko’s body, which most probably caused the rhexis of his liver.”

She remains still for a moment. Then she continues:

“While we were talking in the ambulance, Rayko kept sighing: ‘Vessi, Vessi, I made such a big mistake by not listening to you, but I didn’t think for a single moment that a Bulgarian could hide such violent instincts and that he could be such a sadist. I thought that I wouldn’t be capable of living anywhere else, but now, if God helps me to live, I will take the kids and if necessary, I will swim the Black Sea, just to get out of here. How could I imagine that a person could be so brutally mistreated – did I steal, did I murder anybody, did I rape anybody, why? They treated me with such sadism and such hate, I haven’t read that even in the worst novel…’

“Rayko could barely speak. Probably these were his last moments of clarity, he had three or four blood transfusions later, but he didn’t get better. Two agents stood on guard in the room where he was dying. And when I asked the chief doctor for permission to get in and to hold his hand for a moment, they tried to stop me. Then Doctor Tashev told them: ‘Look, I’m the chief in this hospital. If you don’t like what I do or who I bring in, get out. If you behave like this, I’ll call to have you removed.’

“This was the last time when I saw him alive…

“I never learned how they mistreated Rayko, but back then a nurse took me aside and whispered: ‘Please bring a soft blanket and a very soft pillow for him tonight, at 4 am. He is so badly injured that he feels enormous pain even when he’s lying down. And whenever he turns on his side, blood starts flowing out, his whole body is an open wound…’

“I don’t remember any more from whom I received a matress, a quilt, and a blanket. At 4 am we threw all that over the wall surrounding the Red Cross building. Whether the nurse made up his bed…I don’t know…”

*

On the 18th of November 1944, Rayko Alexiev died.

But four months later, on the 12th of March 1945, the People’s Court convened, and Rayko Alexiev, the dead artist, had to “appear” as a defendant, just one among thousands of others in a chain of mock trials.

First issue of the “People’s Court” newspaper, December 18, 1944

Continuing to search for the reasons why, I cite the defense plea in favor of Professor L. Dikov and Rayko Alexiev that the lawyer, I. Vandova, made almost fifty years later, on the 10th of December 1993:

The great number of defendants and their specific professional characteristics show that a certain group of intellectuals involved in the sphere of culture, science and journalism was pursued. The great number of witnesses, among them a number of famous names, speaks of a conscious strategy of division within the circles of intelligentsia and furthermore, of a strategy to give way to “our people,” to free positions for them and, simultaneously, to keep in constant fear those who were repressed during the trial, as well as their sympathizers.

And because we speak of fear, this trial leads to one more conclusion. An ungrounded accusation leading to a serious conviction says it openly: everybody be careful, because we will do whatever we want with you. The pedagogical pathos of the trial is very clear—a warning to everyone else. Pitting one group of spiritual leaders of a country against another group of spiritual leaders (intuitively or not) was a strategy that took place already in the first days after the invasion on the 9th of September 1944. The arrogance of it is evident not only in the choice of prosecutors—one of them is a poet, namely the Chief prosecutor Nikola Lankov, but also in the choice of witnesses: [the artist] Nikolay Raynov, [the poet] Christo Radevski, [the writer] Slavcho Vassev, [the playwright] Lozan Strelkov, regardless of their testimony.

In fact, the list of writers who took the role of judges in this case is longer. The composition of the jury included: Dimitar Polianov, a writer; Georgi Kostov, a playwright and publicist; and Vesselin Andreev, a poet.

The convictions were announced on the 4th of April, 1945, in the name of Bulgarian people. Eleven of the defendants were condemned to life imprisonment, three of them had fifteen years of solitary confinement, seven of them received a conviction of ten years in prison, six of them received seven years, eleven of them—of five years, three of them—of three years, etc. Only six were released. Fifteen people were sentenced to death (Yordan Badev, already killed, was at the top of that list). Danail Krapchev, General Christo Lukov and Rayko Alexiev, each of them already dead, were all found guilty and their property was confiscated, including the Chevrolet sedan of Rayko Alexiev.

On the 3rd of March, 1993, in his speech at the celebration of the centennial of the birthday of Rayko Alexiev, the writer, poet and dissident Radoy Ralin stated: “Revolutionaries danced daily on the beaten body of the eternal jester until they turned him into a barely breathing living corpse. A future president of the Union of Bulgarian Journalists, Georgi Bokov, boasted that he had given Rayko 400 slaps in the face…”

In total, eleven thousand living people were brought to trial by the People’s Court (the expression used for dead defendants was “missing”). 2730 death sentences were pronounced, 1305 of live imprisonment, and 4305 of imprisonment for a period between one and fifteen years.

*

During my research and interviews, I needed to know more about the psychological nature of what pushed people into torture and show trials. What was the motivation for their actions? That’s how I came into contact with the renowned psychiatrist doctor David Yeroham. I managed to sneak in, between two visits of patients, on a Tuesday in July 2002, in his office at “Gurko” street in the center of Sofia. A man in his fifties, in a blue pullover and worn out jeans. Sometimes distant, sometimes chatty. He left the impression that this behavior is just a trait of a lonely person occupied with his own self, keeping his intuition fresh by protecting it from the bright light and the noise of the outside world.

“How would you explain this repetitive cycle of hatred in Bulgaria?” I asked. “Hatred before the 9th of September, we kill the communists, and hatred after that date, we kill the fascists. Why does it take place again and again?”

Yeroham replied, “Maybe because in times of war there exists a certain disintegration, a certain fragmentation. People are divided according to their political views, according to their history and then they lose connection with reality—this makes them lonely. When a person is lonely, he becomes very anxious, he feels endangered. And, simultaneously, this awakes hatred and envy.”

“You mean that it was all a form of self-defense?”

“Yes,” he says. “In any case it was a self-defense from fear, from anxiety, from isolation.”

I have to ask, “And why were they so evil?”

“There is no answer to this question. In one of Primo Levi’s books on concentration camps, an executioner says: ‘There is no question why, here it simply doesn’t exist.’ It’s a part of our nature and we should simply acknowledge it, know ourselves and be aware of its manifestation.”

“They knew, they were smart, but they didn’t stop it, even though it brought death to their opponents?”

“Smart people!” he says. “I think that is speculation. They believed in a balanced organization of the world. This was fashionable at the time: the world would obey rational intentions and plans, which of course is an illusion and will never happen. So when we say: ‘They were smart people,’ if they believed in such an idea, they were in fact far from reality. That’s why they were so disappointed afterwards. Because no rational organization of the world is ever possible. So they became victims too, probably of their own humanism.”

“It seems that their language changed when they cast blame. The language of their speeches in court doesn’t have anything to do with the language of their books.”

“The opposite of our own selves always exists inside us. Sometimes it manifests itself through words, maybe not always quite clearly. But it gives these words a certain energy that could kill. The testimony of the one group of intellectuals against the other one is the result of such a force. In this case however, the indifference and the lack of empathy for the pain of others seem more horrific to me. Not the revenge, but the suffocation of feelings. And a great number of people kept silent, even when they had the opportunity to save some of their colleagues…”

—Translated by Aleksandra Chaushova

Ivayla Alexandrova (b. 1951, Sofia) is a writer and a long-time journalist for the Bulgarian National Radio, department “Culture.” Working in the field of non-fiction and specialized in the communist and post-communist history of Bulgaria, she is the author of documentary radio plays (such as the 2009 series titled 1989, dedicated to the changes that took place in Bulgarian politics and society at the moment of the fall of communism) as well as the script writer of the documentary movie Vaptzarov. Five Stories for an Execution (director Kostadin Bonev, 2013). Alexandrova is author of the documentary novel Ardent Red (Janet 45 editions, 2008). The novel received the Prize for Non-fiction of “Helikon”, the Big Prize of the Union of Bulgarian Journalists, nominated for the National Prize for Literature “Christo G. Danov.” The most important prize that the novel received was the National Prize for Literature, “Elias Canetti.” It opened the possibility for international presentation of the book, namely at the 10th International Literary Festival in Berlin (2010), the Leipzig Book Fair (2011) and it was presented at the European Commission in Berlin (2011) and the Sozopol Fiction Seminars, organized by the Foundation Elisabeth Kostova (2017).

Aleksandra Chaushova (b. 1985, Sofia) is an artist, living and working in Brussels, Belgium. Her practice is diverse, including graphic printing, illustration, writing and drawing. Her works have been exhibited at WIELS Center for Contemporary Art and La Centrale.lab in Brussels, and Neue Museum in Nurnberg (as a part of her nomination for the International “Faber-Castell” Drawing Award) among others. She won a Vocatio prize by the Fondation Belge de la Vocation and the contemporary art prize BAZA in 2015. She is currently doing a PhD in Art and art sciences at the Free University of Brussels in collaboration with ENSAV La Cambre and teaching as an assistant in the Drawing department at La Cambre. Although writing occasionally and recently mainly in English, the translation of this excerpt of Ardent Red is a first for her.

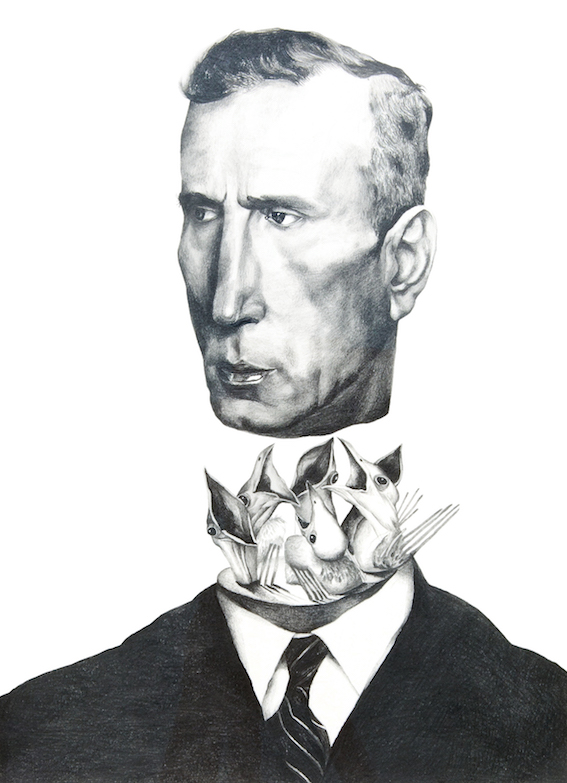

Artwork depicting Rayko Alexiev, “Swallowed Thoughts,” is by Aleksandra Chaushova.

Courtesy of Thomas Zacharias collection, Switzerland