selected for publication by Craig Santos Perez

sponsored by I-Regen at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

The second round of IVF failed exactly the same way the first did: the embryos simply stopped growing. Every other day the lab called with an update. Six embryos, then five, then three, then one. “There’s still one,” each of my parents had said on the phone, hopeful despite everything.

For two days the future rested on this single cluster of cells as we waited for the results of a genetic test. But the one potentially-viable embryo, the only one we’d ever made that actually grew big enough to get tested, turned out to be as un-viable as all the others.

“I’m afraid the test came back abnormal,” the tech said on a wet December afternoon.

“Abnormal,” I said to my partner Mark.

Our doctors did not recommend a third attempt; our genetic material was simply not up to the task.

I thought this was the end of the story of me becoming a mother, something I wasn’t even sure I wanted to become in the first place. But it was only the end of one part, the beginning of another. Before I explain everything that came next, I have to tell you about the octopus.

In 2007, scientists from the Monterey Bay Aquarium sent an unmanned submersible almost a mile deep into the Monterey Canyon. The Monterey Canyon is just as massive as the Grand Canyon and at that depth it is an intensely hostile environment. The water maintains a steady temperature of thirty-nine degrees Fahrenheit. The pressure is around 5,800 pounds per square inch. Not a single photon of sunlight can penetrate what’s known as the midnight zone. It is dark, cold, and crushing. And it was here, along a rocky slope in the vast darkness, that researchers came across an octopus with a distinctive crescent-shaped scar.

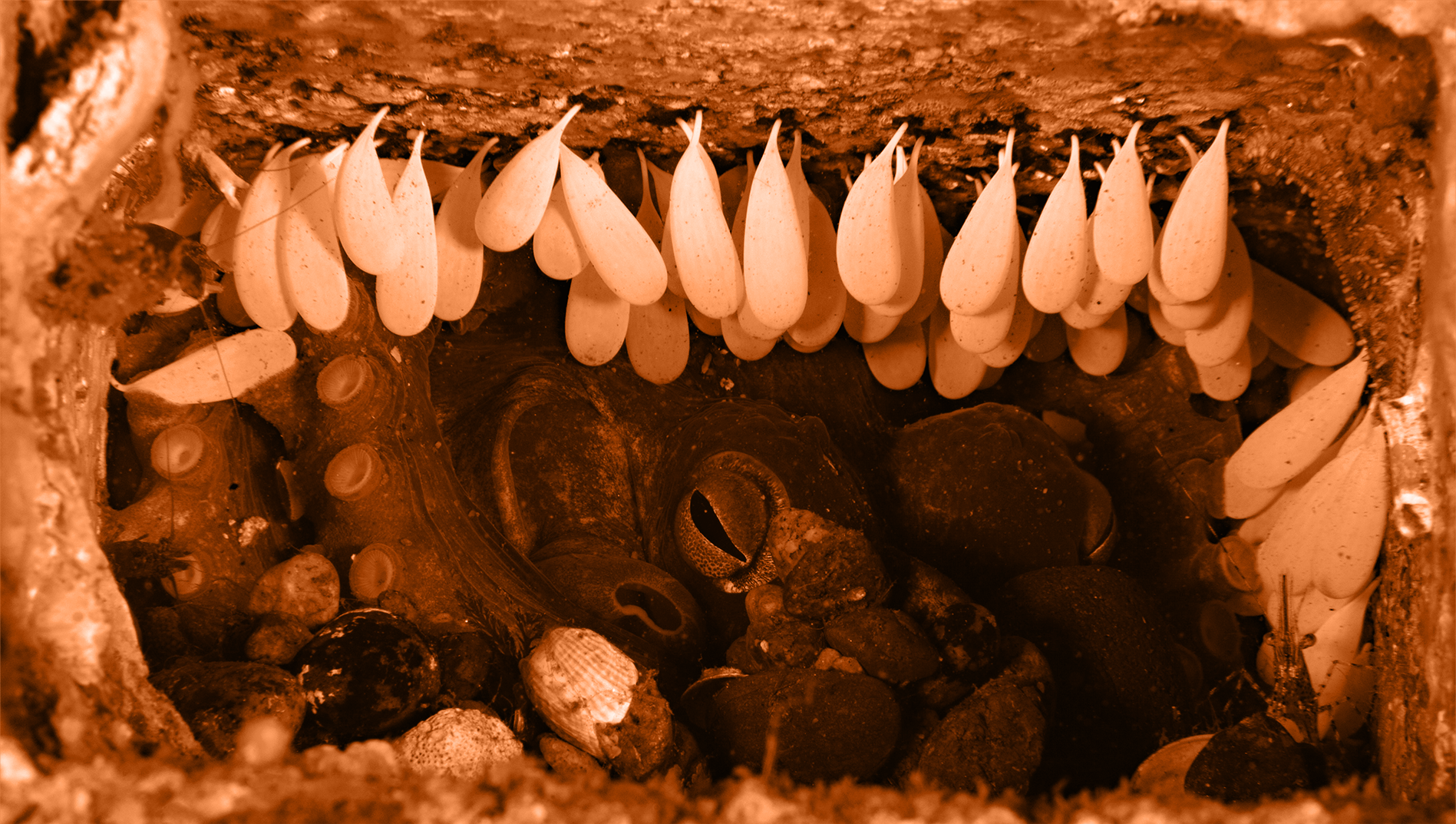

When they returned a month later, they discovered the same octopus (species Graneledone boreopacifica), with her same scar, perched on a clutch of milky, tear-shaped eggs. No one had ever studied an octopus brooding at this depth before, so every few months, when they revisited that part of the canyon, they stopped to check in on her.

It turns out that when a female octopus lays her eggs, it marks the beginning of the end of her life. She devotes all her remaining energy to polishing the eggs, spraying them with fresh oxygenated water, and defending them from predators. She stops hunting and, scientists think, stops eating altogether. She doesn’t move from her spot and her body slowly deteriorates until the eggs are ready to hatch. For a shallow water octopus, this may last a few weeks or even months. But in the deep, metabolic processes can happen far more slowly.

Visit after visit the researchers found the octopus perched on the cliffside, arms curled over her eggs. Occasionally, they would spot crabs circling, hungrily eyeing the brood. But all one hundred and sixty eggs remained. They even used the submersible’s robot arm to break off a crab leg and tempt her to eat, but she refused.

A year passed this way, and then another. The eggs matured. The octopus grew ragged.

On their last visit, a full fifty-three months after they first found her, the researchers identified the tattered remains of the egg sacs. When they looked closer, they spotted baby octopuses among the nearby rocks.

There was no sign of the mother. Most likely, she was eaten by predators. Fifty-three months—that’s nearly four and a half years, the longest known brooding period, by far, of any species on Earth.

I first learned about the octopus on a podcast. It was spring 2020 and I was on my way to a coffee shop. I hoped a cappuccino in a paper cup would conjure some echo of the pre-pandemic life I’d been living just weeks earlier. I wanted to remember what it was to be a person who moved freely through the city.

I knew the octopus’s story was remarkable, but what I felt as I stalked the empty sidewalks wasn’t awe but resentment. We had, at that point, only completed one round of IVF. The pandemic had closed the clinic just as we were preparing for a second. I didn’t know what this would mean for us.

I was not a mother but attempting to become one had meant putting aside more and more of myself. It wasn’t just the cost in time or money (though both were enormous), but also the pages I didn’t write, the Christmases I spent in treatment instead of with my family, the days I lost to despair because the drugs completely hijacked my moods. No one ever suggested that any of this was too much.

No one recommended that my partner try guided meditation or giving up alcohol or (I kid you not) chewing his food more thoroughly. No one even seemed to notice that he was responsible for generating half the necessary genetic material. Because everyone seemed to agree that the burden of reproduction was a woman’s to bear alone.

I was tired of this idea—and bitter, even as I steeled myself to keep going. All of this was on my mind that quiet afternoon.

“It’s so beautiful and heroic and poignant,” said the podcast host.

“They are devoted moms,” said the ecologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

I thought of the women who had already quit their jobs as it became apparent schools and daycares weren’t reopening any time soon.

It was clear that we were meant to understand this remarkable brooding period not as a scientific wonder but as a story of maternal self-sacrifice. To give up absolutely everything, that was the ultimate feel-good narrative of motherhood.

We eventually managed to schedule the second round of IVF exactly a year after the first—only to find ourselves back where we’d started a few weeks later. After the clinic disposed of our single abnormal embryo, we spent January and February in Covid lockdown.

For so long I’d felt deep ambivalence about becoming a mother. I had never longed for a baby the way some folks seemed to. What I longed for was a creative life with vast stretches of time for wandering around in my own mind. But once I’d made that life, I still had this feeling that there was a surplus of something that felt like love inside me. And I needed somewhere to put it.

Becoming someone’s mother seemed like one solution to this problem, but not the only one. Fertility treatments had hollowed me out; I thought I would be relieved to be done with them. But once the possibility of parenthood evaporated, I could see that the life I’d crafted was almost entirely frictionless. Nothing was at stake.

In early March I started feeling lethargic and congested. I went for a Covid test, even though I’d seen no one and been nowhere. When it came back negative, I called my doctor to see if maybe I had a sinus infection. On top of everything, my period was late. The pandemic isolation had finally taken its toll, I thought, and my body was shutting down in protest. I refused to take a pregnancy test. I’d taken so many. That I might have to perform the whole ritual again—buying the test, setting the timer, waiting with clownish hopefulness for the same result I’d gotten time after time—felt unbearably cruel at this point. Eventually, though, I relented.

The second line materialized almost immediately. I ran to the kitchen, the instruction sheet shaking in my hand: “Are you sure I’m reading this right?”

There was an embryo growing inside me. I understood then that I was not in control of my life, even though the promise of fertility treatments was that, with enough money and effort, one could be.

In the months that followed, countless people told me stories about this, about people they knew who’d gotten pregnant immediately after stopping fertility treatments. The explanation was always the same: once you stop trying to get pregnant, your stress vanishes and something magical happens.

I preferred my own story, which was that life simply happens how it happens. It was a relief to accept this reality, though I knew it also meant that there was nothing I could do to make the pregnancy stick—no matter how thoroughly I chewed my food.

Every day I woke up feeling less at ease in my body, which I took to be a good sign. Clothes squeezed the wrong way. Food lost all pleasure. What little I ate refused digestion. My nose bled. My ears hurt. A single errand zapped my energy for the rest of the day.

I’d spent years imagining the kind of pregnant person I would be. I would, like a famous novelist I’d once heard on the radio, give myself nine months to finish drafting a book. And, like the athletes I followed on Instagram, I would hike and climb and bike and ski until it felt too risky or uncomfortable to continue. I would eat pizza every night of the week if I wanted and sneak sips of beer when no one was looking. I would categorically reject the idea of maternal self-sacrifice by being more motivated and focused and alive than ever.

Instead, I lay on the couch, legs sprawled across pillows, eyes closed, wishing I could sleep. Sentences ran through my head like ticker tape, long essays practically writing themselves, though I was too exhausted to get them down. Something was happening to me, a program I could not override. All day, I thought of the octopus, perched above her eggs on the edge of the canyon.

The octopus is what biologists call a semelparous species. In technical terms, semelparity is a reproductive strategy in which every available resource is invested into a single massive reproductive attempt. Every resource, meaning every moment of life remaining, every last bit of energy. In other words, in semelparous species, the act of reproduction itself is fatal; death is woven into the creation of new life.

The Pacific salmon is probably the example most people know best. Every fall they fight their way from the ocean to the spawning ground upriver. Their bodies decompose as they swim against the current, growing tattered and depleted until they arrive—often at the exact spot where they were born. After they reproduce, they survive for a couple of days, or even just a few hours. Their carcasses decay on the riverbed, which may sound disgusting but, in this way, they return to the ecosystem, providing nutrients that nourish the algae that feed the zooplankton that will eventually feed their offspring.

At the first ultrasound, my abs quivered as the sonographer ran the sensor along my skin. No image had appeared on the screen, but already I was on the verge of crying.

I knew the constant low-grade nausea meant the right chemicals were coursing through my body. But at my age—now a week out from my fortieth birthday—the chance of miscarriage was one in three.

The clinic’s Covid restrictions required Mark to wait in the car, but we’d agreed I would FaceTime him when there was news.

“Do you want to know what I’m seeing?” the sonographer asked. “Or do you want to wait until your partner is on the phone?”

If there was bad news, I thought, I would give it to him myself. “Go ahead and tell me,” I said.

“Well,” she paused, and in that pause I could hear the future fracture: into one life where I became a parent and another one where I did not.

“You’re having twins,” she smiled. There were two embryos. Two heartbeats.

None of the futures I’d imagined involved two. I opened FaceTime and turned the phone’s camera to the grainy black and white image on the screen. “There are two babies in there,” I said, watching his face so I could screenshot the moment of disbelief.

Later, I thought of a long-ago night spent wandering the streets of Portland. “You should know I’m only ever having one kid,” I’d said. “One pregnancy. One maternity leave. It’s the only way I’ll still have time to write.”

“That’s fine,” he replied with the confidence of someone who is slightly drunk and newly in love. “We’ll just have twins.”

Unlike the octopus, most mammals are iteroparous species, meaning we have multiple reproductive cycles over the course of our lifetimes. Iteroparous species produce fewer offspring but put more energy into the survival of each one. Which means that each individual has a much higher chance of actually making it to adulthood.

The idea of dying just as your babies are born certainly seems cruel from a human perspective. But in harsh environments where an adult might not survive long enough for multiple attempts at reproduction, semelparity can keep a species alive. It is a calculated evolutionary trade-off.

“So you just turned forty and you’re having twins,” my OB said with a smile as I sat down across from her. “What a wonderful thing to do.” I liked her immediately.

After we discovered the two embryos, my doctor sent me straight to this obstetrician, a woman who’d devoted her career to delivering twins. Ours were monozygotic twins: genetically identical fetuses from a single split embryo. Two fetuses meant higher hormone levels, more nausea and fatigue and constipation (which at least made me feel justified about my now-permanent move from my desk to the couch). I was labeled a high-risk pregnancy—because I was old and because twin pregnancies are always risky, but also because lots of complications arise when two babies rely on a single placenta like ours did.

She explained that I should cancel my summer travel plans. I would need to be in town for monthly checkups with her and bi-weekly ultrasounds at the hospital. I had hoped to see my parents. The pandemic had kept us apart for a year and a half already. But, I told myself, this was it: our one shot at this. We would follow where it led us.

Though I was due in November, my doctor said I should plan to start maternity leave sooner. The babies would come early—thirty-five weeks on average—but it would be difficult to work well before that. “We’ll laugh about this in September,” she said, “when you can barely walk and your belly is too big for your arms to reach around.” Her grin made it clear that I did not understand what was about to happen.

Can I pause here to say how little I cared about everything maternal before my pregnancy—and how wrong I was to dismiss the most interesting thing, by far, that a human body can do? Even during those early weeks, when my body began making decisions without my consent (yes, I had planned to go for a bike ride but instead I would choke down a smoothie and lie motionless in the living room for as long as I could), I still imagined I would reach the second trimester and get back to living. I still believed the right way to be pregnant was to hold tight to some semblance of oneself.

Sometimes I dreamed of rock climbing—not the idea of climbing, but the physical practice of it, the micro-movements of muscles, the weight of limbs shifting over small features on a slab of granite. When I woke from these dreams, I felt something like nostalgia for what my body used to do, for who I used to be. Each day I felt more…inhabited. There is no other word for it. Someone was there—two someones—stealing my energy, ruining my appetite, making me strange to myself.

After she lays her eggs, an octopus essentially shuts down the parts of her brain that she doesn’t need. Because this is what it takes to survive those dark weeks—or years. Only the optic glands—two tiny spots, each the size of a grain of rice—remain active. This is how she avoids using any extraneous energy. Even as she is deteriorating on the outside, she is focused and alert in the depths of her brain. She does what needs doing while the rest falls away.

The moment I understood something was wrong came halfway through a routine ultrasound at eighteen weeks. A student was sliding the wand over my belly under the watchful eye of a sonographer. I had recently begun to look unambiguously pregnant. I could not yet feel movement inside me, but I was constantly on alert for it, attending to every stomach growl and gas pain. What I’m saying is that though I had incontrovertible evidence of their existence, they were not yet people to me, their bodies not distinct from mine in any way I could discern.

The sonographer patiently talked the student through the exam, measure by measure, until they both went quiet.

“I’ll take over from here,” the older woman said. The three of us—me, my partner, the student—waited in silence while she worked. When the two women left to get a doctor, I felt a sensation that would eventually become familiar: loss pacing on the other side of a curtain.

After a quiet eternity, the doctor arrived. He explained that the images showed signs of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome—a rare condition that was fatal if left untreated. The problem was with the shared placenta: one fetus was getting too much blood and the other not enough. This endangered them both.

He drew a small diagram with his ballpoint pen as he spoke. It was clear he had done this before. We had a few options: do nothing and wait for the pregnancy to end on its own, terminate the pregnancy and hope for a better outcome in the future, cut the supply of blood to one fetus in hopes the other would make it, or undergo emergency laser surgery to the placenta with about a fifty-to-sixty percent chance of saving both fetuses.

Scientists estimate that only about one percent of giant Pacific octopuses make it to adulthood. So for every octopus you see on TV or in the aquarium, imagine ninety-nine others lost to the whims of the ocean. Some estimates are even lower, suggesting that a fifty-thousand egg clutch will yield just enough adults to keep the population stable: only two who survive long enough to reproduce.

The giant Pacific is a shallow-water octopus whose young emerge from their eggs smaller and less developed than their deep-water counterparts. In fact, the four-and-a-half-year brooding period of Graneledone boreopacifica not only means she almost certainly lives longer than any other octopus, her offspring are also bigger and more mature, potentially increasing their odds of survival. Still, very few are likely to live as long as their mother.

Two days later, I stood in a hospital gown in a hallway outside an operating room. I could feel the cold linoleum beneath my paper booties.

I considered everything that could go wrong. I could go into spontaneous labor and deliver two babies who were too small to survive on their own. I could lose one baby and then wait to see if the other would hang on until he was big enough to live. I could carry the babies to term and discover that one or both had congenital heart defects or chronic lung problems or any number of other developmental challenges. It was too late to wonder if we’d made the right choice.

A nurse stretched an arm across my shoulders. “You are in good hands here,” she whispered. I nodded, unable to speak.

The room was white and bright and full of people. This was a rare procedure so interns and residents had come to watch. As I walked to the table, I remembered that the operating room is sometimes called a theater and for the first time I understood why. I also understood that, in this analogy, I was not an actor. I was a prop.

Someone settled me onto the table and from there things moved quickly. My arms were strapped down, drugs were administered. A warm sense of well being crawled into my veins and my anxiety evaporated into the cold, sterile air. I would be awake for the procedure, but groggy. The anesthesiologist asked if there was a particular kind of music I would like to listen to and my brain emptied of everything except the words “Justin Bieber,” which I knew were the wrong words so I stuttered and finally said, “Uh, anything is fine.” I don’t remember what she played. I don’t remember hearing music at all.

I do remember the buzz-pop sound of the laser snapping inside my body. And the awe in the room the moment a tiny foot floated in front of the laparoscope and appeared on a screen just out of my sight.

Afterwards, I was not wheeled back to the antenatal ward, but to labor and delivery. I understood what this meant. Every few hours, nurses arrived and strapped sensors to my belly. One for each baby’s heartbeat. One to monitor my uterus for contractions. A small machine printed a record of this activity. Sometimes they struggled to find both heartbeats and they slid the sensors around and around until the ultrasound gel gunked up against my skin and had to be reapplied. The babies were still so small, they explained, and there was so much room to move around in there. I dreaded these visits.

Can an octopus feel fear? Does she know, when she is laying her eggs, that she is setting into motion a course of events that cannot be reversed? Does she worry about how her babies will do out in the vast dark without her to defend them? Does she feel lucky to have lived this long at all?

Octopuses are intelligent creatures with sophisticated nervous systems. As far as I can tell, no one has tried to measure their experience of fear, but a recent study argues that it is likely they experience pain—both physical and emotional. The researchers describe it as a “lasting negative affective state.” What they mean is that when they inject acid into one of her arms, the octopus notices. She dislikes it. Later, she remembers and seeks out places that have no association with suffering. I’m not an expert but it seems to me that trying to avoid suffering is not so different from being afraid of it.

Octopuses are clever and curious and drawn to interactions with humans. But they are also entirely unlike us. Biologically speaking, we have more in common with dinosaurs than we do with cephalopods. Our nearest common ancestor lived about six hundred million years ago, when there was only a single continent surrounded by a single, enormous ocean. Making others in our own image is such a human thing to do, but the octopus’s sentience is so unlike ours that any attempts to imagine it are guaranteed to fall short.

I understand all of this, yet I still want her to tell me something about survival. I want to know everything she knows about love and fear.

The doctor who performed my post-op ultrasound said everything seemed to have gone as planned. I was relieved but also wary of celebrating; so much could still go wrong. Maybe my caution read as a lack of gratitude. “Do you know how lucky you are?” she asked. I felt scolded, like a teenager who had wrecked her car but somehow managed to come out unscathed.

There was nothing to do but keep going. I woke up before dawn and blinked into the darkness and I did not think about the future. I did this first in my hospital bed and then in my bedroom. Every day I woke up and thought, “I’m still pregnant.” I ate lunch. “Still pregnant.” I brushed my teeth and showered and went to bed, always attending to my body for signs of disaster.

My iron dropped so low I could only walk for about ten minutes at a time. I promised the doctors I would take it easy for a couple of weeks, but there was no real choice about it. I made no plans. I abandoned all pretense of work or productivity or even pleasure. Again and again I remembered that I was not in charge of the events of my life. I was not even in charge of my own body. Or its inhabitants. Eventually, I began to feel them floating around in there, thriving despite my exhaustion, oblivious to any threat to their existence.

I referred to them as “babies” because “fetuses” was too clinical. But they felt like in-between beings to me, little proto-people who were as inaccessible and unknowable as the octopus. I wanted them to become part of our family, but I also knew that we had done what we could. Now it was up to them.

When you Google “octopus mother” the articles and videos that appear are practically breathless in their awe. “The world’s best mother” reads one headline. “No mother could give more” reads another. NPR describes the giant Pacific octopus as “the hardest working mom on the planet.”

Even if you search the less loaded phrase “female octopus,” almost every result is about her reproduction and eventual death. Before she breeds, one article notes, the octopus is “an agile and aggressive hunter.” Motherhood does not simply tame her; it transforms her entirely.

We are captivated by the idea of maternal sacrifice. The podcast that first introduced me to the octopus was only one of many stories told the same way. Sometimes, when I explained what was happening with my pregnancy, I worried I was telling the same kind of story.

It’s so difficult to talk about the physical, biological experience of reproduction without also summoning the cultural baggage of motherhood. As anyone with a uterus can tell you, our bodies are always being turned into lessons. The pregnancy demanded more of me than anything I’d ever experienced, but I never felt “strong” or “brave” or even confident that we’d made the right choice by keeping the pregnancy in the first place.

At a follow-up ultrasound, the maternal fetal medicine specialist confirmed that the surgery had been successful—but, during the procedure, the membrane separating the two amniotic sacs had ruptured. “I’m so sorry,” she said, though I didn’t yet understand what this meant.

Later, in her office, she explained. I was now carrying a mono-chorionic, mono-amniotic pregnancy—one placenta, one amniotic sac—the riskiest kind of twin pregnancy. Now that they were swimming in the same little pond, the babies’ umbilical cords could become entangled and compressed.

She explained that at twenty-four weeks, I would need to move into the hospital for monitoring. I should be prepared for delivery at any time. (There was no need to monitor earlier because no intervention could save them.) She would set up a call with a NICU doctor who could talk us through the risks of prematurity, week by week. Our best hope was that they made it to thirty-two weeks. At that point they would be delivered by c-section, because that was when the scales tipped: the risks of taking them out were lower than the risks of leaving them in.

“A lot of people think this is unfair,” the doctor said. “They wonder, ‘why is this happening to me?’” I guess, in her brusque French-Canadian way, she was asking about my mental health.

I tried to explain that I was not someone who spent time wondering about the causes of her own bad luck. Things happen. Statistically-speaking, some parents of twins will end up in this situation. Why not us?

But no amount of chin up pragmatism could stop me from feeling like I’d gotten my foot stuck in the tracks between birth and death. It was strange: the babies were closer than ever, and also more of a danger to one another; they were inside my body but entirely out of reach.

The octopus is not my avatar. She is not a symbol or a metaphor. Our experiences are not alike. But maybe what we have in common is the knowledge that both living and dying are written into our bodies, that every beginning contains its own ending, even though we cannot decode or control it.

Nothing anyone told me about pregnancy turned out to be true. It was not serene or joyful. My body did not feel beautiful or powerful. I didn’t daydream about the future or feel especially connected to the people growing inside of me.

The weeks in the hospital were not easy. Every time a nurse came into my room to check their heartbeats, every time I walked downstairs to the ultrasound clinic, the fear returned. But, by the end, I did feel changed.

I was still not a mother, but I was someone who was capable of doing what needed to be done and letting the rest go. I don’t mean giving up on my book proposal or undergoing surgery or even moving into the hospital. I mean living day to day with the very real possibility of loss. I don’t think I was special for doing this. But, if you’d asked me at the beginning, I wouldn’t have believed I could.

At thirty-two weeks and four days, the babies arrived as planned. They were not yet able to breathe or eat on their own, but, with the help of three separate teams of healthcare professionals (one for me and one for each of them), they emerged, seemingly ready to join the world. When the nurses finally placed them on our chests—these tiny people adorned with endless tubes and wires—the force of their presence was startling.

Now, nine months later, they are no longer strange to me. They are squirmy and loud and their clothes are always appallingly damp. They think I’m funny and they love—love—my dog impersonation. I finally feel like a mother—not because I am making extraordinary sacrifices, but because I am constantly negotiating between their needs and my own. This version of motherhood is chaotic and foggy with sleep deprivation. It is distinctively human.

The story of the octopus is that the burden of reproduction is the mother’s to bear alone. But it turns out the story is missing crucial information. The thing almost no article mentions is that the male octopus also dies soon after mating. His body seems to undergo a similar process of senescence, slowly starving until he is weak and easily captured by a predator. You could tell the same story a different way: the female octopus doesn’t sacrifice her life for her offspring, but extends it. Caring for the eggs keeps her alive just that much longer.

I want there to be a better way to talk about what we give up for one another, about how sometimes one must do what needs to be done, even when it is hard—not because it is beautiful or poignant, but simply because you are the one who can do it. To live and keep living, to see that others keep living too, to sustain a family, a species, a planet, this is difficult, necessary work. It is the work of care.

Care is not the exclusive terrain of mothers. It is simply what the wild and unpredictable phenomenon of life requires of us. Of all of us.

I found a YouTube video of octopus eggs hatching. The thin, translucent membrane stretches then tears and out bobs a tiny, perfectly formed hatchling. Her skin shifts from red to white to red again, pulsing with life. As her siblings emerge and cluster above the ripped egg sacs, an enormous arm sweeps over them, pushing them out towards their fate. And as I’m watching, I feel it in my chest: the stakes are so high.

Mandy Len Catron is the author of the critically-acclaimed essay collection How to Fall in Love with Anyone. The book was listed for the 2018 RBC Taylor Prize and the Kobo Emerging Writer Award. Her writing can be found in The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Guardian, The Rumpus, Catapult, and The Walrus as well as other newspapers, literary journals, and anthologies. Her essays and talks have been translated into more than thirty languages.

Guest Judge: Dr. Craig Santos Perez is a native Pacific Islander from Guam. He is the co-editor of six anthologies and the author of six books of poetry. He is a professor in the English department at the University of Hawai’i, Manoa, where he teaches creative writing and eco-poetry. His poetry has received multiple awards, including the 2023 National Book Award, a 2015 American Book Award and the 2011 PEN Center USA Literary Award for Poetry.

The Regeneration Literary Contest is sponsored by I-Regen. I Regen fits into the iSEE research theme of Secure and Sustainable Agriculture. Originally called the Illinois Regenerative Agriculture Initiative and sponsored in 2020 by Fresh Taste, the Initiative was renewed and renamed in 2023 with funding by the Midwest Regenerative Agriculture Fund (MRAF). I-Regen is a partnership between the Department of Crop Sciences, the College of ACES, U of I Extension, and iSEE.