selected for publication by Robin Marie MacArthur

She met him at Waffle House to tell him how much she hated him. He agreed to feeling the same. She spit in his scrambled eggs. He knocked over her mug of lukewarm coffee, and it dribbled into her purse. When she wasn’t looking, he pocketed the tip she’d left so the waitress would hate her too.

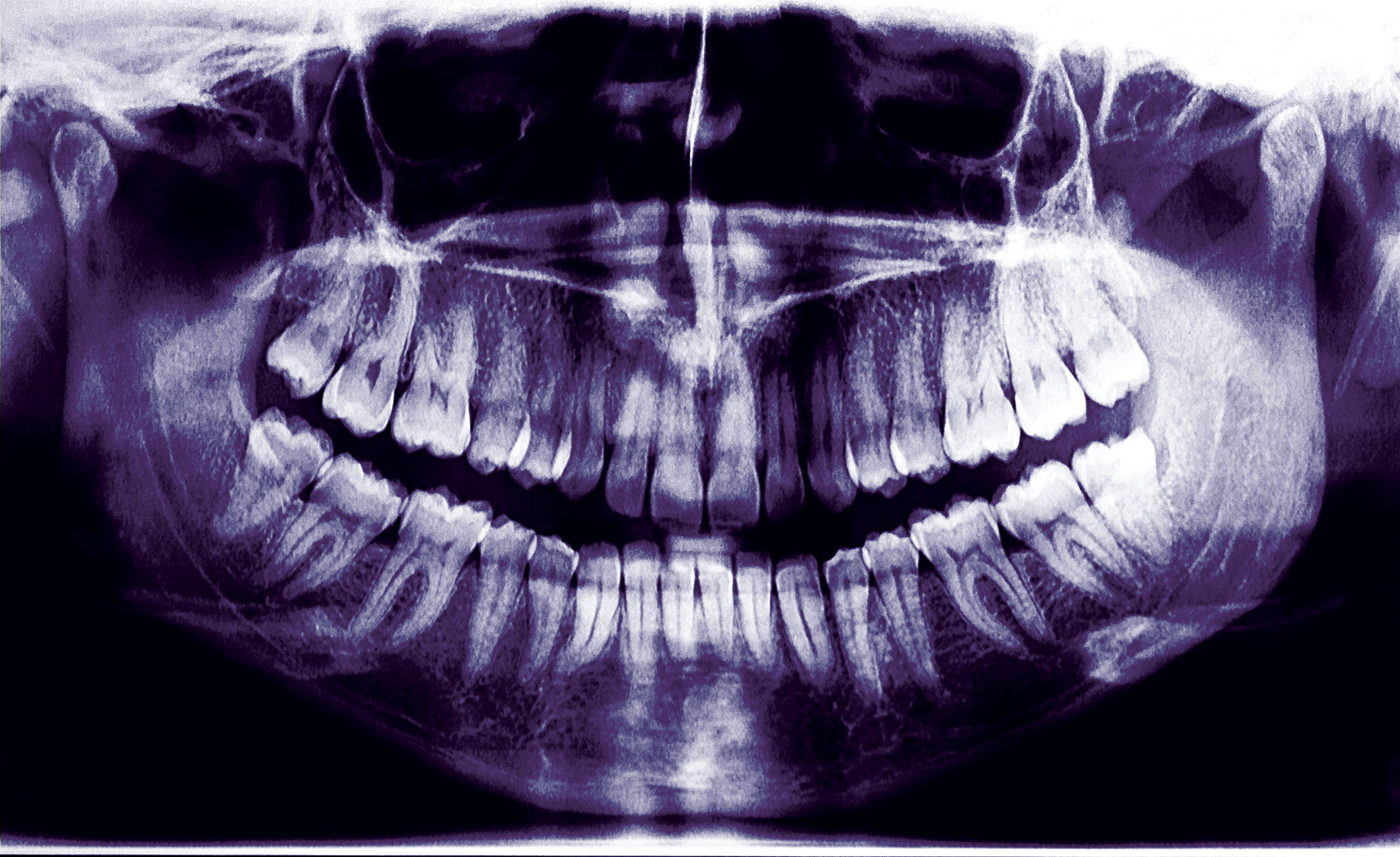

Inside the handicap stall of the women’s bathroom, they pressed their backs and palms against the cool, dirty tiles. There, they reached inside each other’s mouths. Each of their fingers clenched the other’s molar. They raked at their raw gums for long minutes. They rocked the molars back and forth on thorny pivots. Blood ringed their wrists once they plucked them free. The roots stretched long as nightmares with sharp, cruel claws. They each pressed the other’s tooth into their own throbbing sockets.

He called to say she’d ruined his life. “What life?” she replied. His body’s best years. He could’ve had any woman. He was beautiful then and now his hair was thinning and his stomach soft. She preferred the ways in which his body had thinned and softened, but she didn’t tell him this. Thinking about his skin, the pale stretch marks of his ass and the mole on his shoulder, made her gums pulse. She crushed the phone against her ear, so hard it burned.

She told him he was pathetic. She told him he was a child. She told him to fuck off and grow up and grow a pair and to stop calling. They licked their teeth in shared silence. Neither ended the call for many more breaths.

She taxied him to buy a new pickup truck. His died at work on Friday. While she drove, she told him what a miserable bastard he must be to not have a single friend willing to do him a favor. Everyone disliked him.

The seller advertised the truck as a twenty-year-old Ford Ranger, reliable enough despite its age, though marred in rust and dents.

“Sounds like you,” he said when they’d reached the seller’s gravel driveway, the stones grinding like snapping bones underneath her tires.

“At least I don’t look as old as you,” she said.

Splotches covered his skin, a smattering of dots on his forehead and a brutally tanned back of the neck. He indeed looked ten years older than thirty. He worked as a roofer, had subjected his skin to sun without wearing sunblock. He smoked two packs of Winstons per day. His teeth had gone yellow. His mouth always tasted like smoke. No one told him to stop smoking because he’d worked hard to own his own tiny roofing company, two employees from Guatemala and two saddle toolboxes full of hammers and prybars and blades and saws, though no working truck to house them. “I’m younger than you by six years,” he said, “and that will always be the case. You’ll die first. I’ll walk over your grave and just keep walking. Just like you’re a stranger.”

“Keep smoking. Keep working all day in the sun,” she said. “Then we’ll see.”

His arm quivered as he yanked at his own front tooth. To make sure he didn’t finish first, she wrested hers, too. They slid them out alone together, the maxillary incisor, like a tiny tombstone barbed with a dagger. They stabbed them inside each other’s scarlet sneers, much more stubborn going in then out.

He drove a stepladder to her house two weeks before Christmas and held the ladder for her while she strung blue lights along her gutters. He didn’t mention how pointless it was. He knew the importance of this ceremony. If she climbed ladders every day, perhaps it would be unremarkable. But she worked from home, writing how-to articles for the internet. He read them all: how to fix a flat, how to reset smoke alarms, how to meditate, how to poach an egg, how to set up your printer, how to organize family photos, how to reorganize a closet, how to convert a bedroom to a home office, how to arrange for cremation. They’d buried their son in a casket, embalming fluid pumped through him, makeup applied, open casket. He’d looked like a doll. Completely untouchable. It had been useful to see him this way, he told himself, to know he was really gone.

They’d never talked about this. They never would.

She strung lights swiftly because she knew the best way to hang Christmas lights, the best hooks to use. She’d written a how-to article about it. That and their son had loved Christmas best. Even though he’d grown skeptical of Santa at age six, he’d still clamored for every ritual: the big trees, the fireplace and stockings, the hot chocolates and caroling, the drives to ogle lights. They’d gotten ten Christmases with him.

They didn’t talk about those Christmases, either, though they were both remembering them.

He held the ladder. She hung the lights. The house turned blue.

She got too drunk. She punched another woman at the bar. They took it to the parking lot where she fought this same woman to the ground, where she kicked until the woman stopped moving, only moaned. Her victim spit out a tooth, and she took it, then ran into a cornfield where the husks shushed her heart beating like thrown rocks. There she called him. He came. They drove in the new-old Ranger out into the dark-quiet of endless night. They parked and he let her punch his face. She squeezed the woman’s broken tooth in her fist while she swung, and it bit her skin. He welcomed the throbbing, the purple and green that would become a pain he could watch darken. She told him he should apply ice soon, later heat to hasten lymphatic drainage. Also, he should eat pineapple. She’d written about how to treat bruises, of course. She’d researched how to make them disappear.

She texted to tell him he was a drunk. And that his mom was a bitch.

He emailed to tell her she was a hypocrite. And she was a classist. She’d learned it from her father, who was also a racist.

They met in the parking lot of the Chuck E. Cheese where they used to go. There, they agreed to stop writing to each other, to stop all communication. He called her hysterical, called her fat, called her cruel and selfish and ignorant of anyone living a life less privileged than her. She told him he didn’t know how to think for himself, an automaton, only able to ape the liberal blather spewed from the NPR he listened to all day while working on the roof. He was ugly. He was lazy. He was a doormat, a dumbass, and exploitative of his two Guatemalan workers he paid only twelve dollars an hour on a 1099.

They traded cruelties until the parking lot emptied. Their tongues tasted raw. He wanted to bite hers. She wanted to punch him again, so badly, but he liked that too much. Instead, they climbed into the new-old truck bed, where they tugged each other’s cuspids. They traded, and his yellow tobacco stain now winked through her scowl. Her mouth tasted like pennies and stone.

They didn’t talk for weeks after the cuspids. For two years, they hadn’t said their son’s name. Sometimes, she expected divorce papers to show up, but she knew he was too disorganized. Sometimes, he expected to see new posts on her social media, pictures of her grinning teeth, toasting drinks, arm around a new man. But she never posted. And even stalking her accounts led to anxious terror that made her teeth inside his jaws sting, because the last posts were still there. The ones from before, from the time they shared when there was a third person they shared.

They didn’t talk about this.

She sent him a postcard, a cute yellow dog sleeping on the porch of a wooden shack backgrounded by mountains. “Thinking of you,” the picture side claimed. On the back, she’d written Fuck you.

They met and pressed bodies inside the bathroom of a Walgreens. They locked hips while they fished into each other’s mouths, prying at slippery lateral incisors. It took longer than either expected for such a small tooth that was anchored by a monstrous root. Between their feet, a pool of saliva and blood formed an oval like a third tortured mouth. Her shoes tracked red prints across the white tile. She left the bathroom first, hair wetted in sweat. She zippered her jacket over her spattered shirt. She bought cough drops, menthol flavored, because she’d feel bad if she’d didn’t purchase something after leaving such a mess in the bathroom. He walked out without even glancing around the store. The cashier’s mouth clicked and she shook her head.

“Some people are so rude,” she said to the cashier.

“They’re all like that,” the cashier said.

Everyone? she wondered. Or did she mean all men? Or did she mean her husband’s skin color? Or did it have to do with his torn, asphalt-pocked jeans and cutoff sleeves on his “A+ Roofing” T-shirt?

She didn’t ask.

She sucked on the tobacco coating her new tooth.

She ran her key along the red car she guessed belonged to the cashier.

“Most people don’t know how to properly floss,” she told him. They sat in his truck’s cab, watching his two-man roofing crew at work. The truck was off, windows rolled mostly up, and she felt she might choke on his secondhand smoke.

“People floss?” he said, flicking ash out the crack in the window.

“The few who do don’t know how.”

She couldn’t remember their son flossing. Only the dentist demanded it. He’d still had five baby teeth.

“Would you like me to floss?” he asked. “Would that make this easier?”

She didn’t respond to his stupid questions.

She wanted him to slap her. It wasn’t fair that this went only one way. It was sexist, misogynist, to think a woman couldn’t take it, to lean on the flimsy crutch of male chivalry or some bullshit like that, while simultaneously despising and degrading her.

“I do despise you,” he said, but he would never hit her. He lorded this above her, and he knew it hurt worse than his hands could.

She pulled his carton of Winstons from the glovebox and chucked packs out the window as he drove. She ripped the last pack from his breast pocket and crumbled each cigarette into tobacco confetti that sheeted his upholstery. She plucked the last lit cigarette from his lips and smothered the cherry between them on the seat.

He still wouldn’t hit her.

Instead, he parked the truck on a dirt road, so deep into the cornfields they couldn’t even see a house. He took the keys and walked away from her. He walked for miles, his lungs burning for another cigarette. Hours later, when he returned, she was gone. He needed a cigarette so bad he scooped shredded tobacco from the floor and tucked it beside his gums. He nursed this slow drip all the way to the nearest gas station.

They didn’t talk.

They didn’t talk.

They didn’t talk.

They met outside an adult toy shop and sat in their own vehicles. They agreed they hated each other too much to share his truck cab again. Also, it was easier not to talk here where they could focus on the patrons hunched in shame and desperation or those few so giddy to find sex still existing in the world and not just on computer screens. They met outside a liquor store. They met outside an auto parts store. They met outside a pot shop. They met outside a vaping store where he blew real smoke out his window at these fools lying to themselves.

It was easier not to talk in these parking lots where only adults ever roamed.

They’d slip bloody napkins through the cracks of each other’s side windows. They’d unfold these reddened gifts and find teeth to replace their newly weeping sockets.

She wrote a how-to article on roofing using common asphalt shingles. She made it seem so simple anyone could do it, only seventeen steps. Starting a compost garden required twenty-one steps. She knew he’d hate the article. She savored his imagined anger the whole time she was writing it. She ran her tongue over her mouth filled with mostly yellow teeth, all but five replaced now. Her breath tasted like an ashtray. It made no one want to talk with her, which was fine, which was preferred.

Shortly after she published the roofing how-to, he left dozens of comments, critiquing most of her steps. He’d gone deep into the back-and-forth threads with a user named handy_hank79.

Their debate over metal roof superiority had devolved into promises to beat the shit out of each other in real life. He even left a date and time for them to meet in a bowling alley parking lot.

She drove to the bowling alley at his proposed date and time, but as far as she could tell, handy_hank79 never showed, nor did the Ford Ranger.

He didn’t say the truth, that he missed their son so much more than he hated her. She didn’t say it, either. They shared this, the missing being stronger than the hating. Saying so was redundant. Saying this aloud would solve nothing.

He didn’t show up the next Christmas to help her with the ladder and the blue lights. Instead, his two Guatemalan workers arrived smiling. She couldn’t be cruel to them when they worked so quickly and were so polite. She wanted to tell them that she preferred to climb the ladder, to string the lights, to feel too high up, high enough that she could fall and die. He knew she preferred this, craved that part of the ritual. This was why he’d sent his Guatemalans. They finished before she could even offer them water.

As they were leaving, they gave her a small box. “From the boss,” they said, smiling, probably imagining some lovely gift from their employer. She opened it in front of them, the back molar, yellow as a corn kernel. She told them to wait while she ran inside to fetch pliers and pry the tooth from her jaw. She put her own tooth in the same box and sent it back with the now unsmiling men.

A stranger claiming to be her neighbor stopped her outside when she was getting the mail. The stranger told her a man had knocked on his door. The stranger told her the man had shoved this note into his hand. The stranger passed her a thin slice of yellow paper, folded once. The stranger asked if she was in danger, if the man was dangerous, if he himself was in danger. He could call the cops. He kept a pistol near his bed. “Everyone should,” the stranger said, “just in case.”

She’d written about how to safely store guns at home. She’d written about how to clean both revolvers and semi-automatic pistols. She hoped this stranger hadn’t read anything about gun safety.

She navigated to the address listed on his yellow note. She drove in growing darkness. She arrived at an old house, a tall one, sprawling, beautiful and ornate. Out front, one ladder sliced across a row of windows all the way to the roof. She climbed carelessly, losing a shoe on the thirteenth rung. He sat upon the roof peak and blew smoke into the moon. She crawled up the roof pitch and sat beside him.

“What?” she said.

“Wait.”

So they waited for him to chain-smoke three cigarettes. She thought of things to say to him, to ask, but she’d grown skilled at suffocating words within her sealed mouth. And he’d learned to blow his words into smoke and tar.

A glowing red flashed on around them. She’d never seen a roof strung in so many Christmas lights, and to stand amongst the gaudy display was to feel one’s body turned illumination. The colors were hideous. Instead of the blue she loved, that her son had loved, this house was decked out in a rainbow of colors. Still, her son would’ve begged her to slow down driving past here, so they could all ooh and aah together. She could feel her body casting a dark silhouette against the display.

He didn’t say anything. He remained seated until she rejoined him on the peak. He handed her pliers. Together they tugged the last tooth. Together they pressed the pierce of foreign roots into raw sockets. This would be the last time their mouths would fill with blood, the last time they’d trade. They knew each estranged tooth better than any other ever would. And when they spoke, if they spoke, the words would pass through someone else’s teeth, through the only other teeth that could ever know such rabid hurt. They could say it. They could name it. They could. All he had to do was open his mouth. All she had to do was part those tainted teeth and speak.

Dustin M. Hoffman is the author of the story collections One-Hundred-Knuckled Fist (winner of the 2015 Prairie Schooner Book Prize) and No Good for Digging. His newest collection, Such a Good Man, is forthcoming form University of Wisconsin Press. He painted houses for ten years in Michigan and now teaches creative writing at Winthrop University in South Carolina. His stories have recently appeared in New Ohio Review, Gulf Coast, DIAGRAM, Fiddlehead, Alaska Quarterly Review, and One Story. You can visit his site at dustinmhoffman.com.

Guest Judge: Robin Marie MacArthur lives on the hillside farm where she was born in Southern Vermont. Her debut collection of short stories, HALF WILD, won the 2017 PEN New England Award for Fiction and was a finalist for both the New England Book Award and the Vermont Book Award. Her novel, HEART SPRING MOUNTAIN, was an IndieNext Selection and a finalist for the New England Book Award. Both of her books have been translated into French and published by Albin Michel. She teaches at Vermont College of Fine Arts’ MFA in Writing and has taught in many non-traditional settings including the Bread Loaf Environmental Writers’ Conference and Orion Magazine. She is the founder and director of Word House, an emerging writing space in southern Vermont; her essays and stories have appeared in Orion Magazine, LitHub, Hunger Mountain, The Washington Post, Shenandoah, Alaska Quarterly, and on NPR.