Grace Loh Prasad

Album

- The Man in the Suit (1960)

On the observation deck of Sungshan International Airport in Taipei, a young man smiles at someone invisible, revealing white teeth. His shiny black hair is newly trimmed, and his horn-rimmed glasses rest on cheekbones made more prominent by the dismal rations he received during his year of compulsory military service. In his left hand he holds an open umbrella, which looks like a giant ten-petaled flower against the bright summer sky. Standing directly in front of him, with her back to the camera, is his future mother-in-law, still slender in her dark, tight-fitting chipao with the high collar and little cap sleeves. She is fussing over his lapel, fastening a delicate silk flower that she made for him the night before. She also supervised the making of his first real suit, insisting on taking him to the family tailor in Hsintien who makes all of the stylish dresses she wears to church. It’s important for her future son-in-law to look perfect as he embarks on this momentous journey halfway across the world. It’s his first time on an airplane, and the trip will be long—more than twenty-seven hours and three stops before the Mandarin Airways plane touches down an ocean and a continent away at La Guardia International Airport in New York. There, on the other side, he will meet up with his future wife, who has already been studying at Princeton for one year. She has been waiting for her sweetheart for so many months; she has so much to tell him about America. At the same time, she can’t wait to speak Taiwanese again, to catch up on family gossip, to unwrap the sweets and gifts he has brought her from home.

In another photo, he is standing on the rolling stairway that leads to the plane’s door. Halfway up, he turns and with his free hand makes one final wave to a crowd of friends and relatives who’ve come to see him off, enough people to fill several taxis. He looks like a young ambassador, poised in his new suit, palm raised as though taking an oath or baptizing a new convert. His smiling eyes show no fear; he seems comfortable with this new mission, this scholarship to study Western theology at one of the world’s most prestigious seminaries. In a few minutes he will take his last breath of the fragrant humidity of Taipei, committing to memory the mountainous landscape and the proud faces and farewell wishes of his five brothers and four sisters, his mother and father, and countless others. He will leave this sea of familiar faces and go to a city and country where he knows no one except his college sweetheart. He will train his tongue to speak the new language, adjust to using plates and silverware instead of bowls and chopsticks, and eventually learn to drive a car. Together, the young couple will begin a new chapter in their lives—their American education, their first experience of the world outside of this sweet-potato shaped island. It is the first of many migrations my parents will make.

- The Grotto (1960)

She stands in front of a large glass window framed with white lace curtains. Her face is scrubbed clean and she is smiling and squinting in the bright afternoon sun. Her crisp white dress and apron contrast with her long black hair, pulled back in a ponytail. Behind the window is a refrigerated case filled with desserts and pies, next to a potted plant. The name of the restaurant is painted onto the window in a graceful arch: “The Grotto: Italian American Cuisine.” Below, on the windowsill, a handwritten sign announces “MUSSELS TO-DAY.” It’s a classic photo, a young woman proud to be working at her first job, an immigrant eager to do well and move beyond her humble beginnings. The only surprise, among the Italian accents and the smell of basil and tomatoes and pizza dough, is her Chinese face.

Working at The Grotto was a way to support herself while studying at Princeton Theological Seminary. She arrived in New Jersey in 1959, a year ahead of her fiancé, who had to complete a year of military service before he could join her abroad. Though she had majored in foreign languages at National Taiwan University, she spoke English haltingly and avoided unnecessary conversations until her confidence grew. Despite her shyness, she managed to get a waitressing job at a respectable Italian restaurant just off of Nassau Street, not long after she arrived.

Initially, she had a hard time pronouncing some of the Italian words. She couldn’t tell manicotti from cannelloni, and would simply try her best to repeat what the customer said to the kitchen staff, whether she understood the meaning or not. Ma-ca-ro-nee. Spu-mo-nee. Lin-gwee-nee. Even more amusing to her than the multi-syllabic Italian entrees was “succotash,” the word they used for a side order of peas, carrots and corn.

She learned to like spaghetti, even though the noodles were not at all like the ones she ate in Taiwan. Italian pasta was denser than Chinese noodles and came in infinitely more shapes and sizes. The superficial resemblance made her yearn even more for the tastes of home: bihun rice noodles, buckwheat soba, chewy ramen and meat-filled dumplings in broth rather than cheese ravioli in red sauce. The scent of chopped garlic transported her to her mother’s kitchen, where its aroma would mingle with ginger and green onion and perfume the whole house whenever her mother cooked.

Her own efforts at cooking were minimal at best, since she lacked a proper kitchen in the small room that she rented during her first year at Princeton. She took advantage of the free meals at The Grotto, or ate in one of the dining halls on campus most days. Her wages from waitressing didn’t buy much so she learned to be thrifty, though she allowed herself the occasional splurge like a new pair of pantyhose from Woolworth.

She must have been a good waitress, because years later she would visit The Grotto with her family and greet her old employers. Her foray into Italian cuisine proved useful in her assimilation: she regularly cooked spaghetti with Ragu for her two kids (something her mother never made for her) and she developed a lasting appreciation for a good, old-fashioned, unadorned slice of pizza.

- White (1962)

All of their wedding photos were lost in the mail on the way to or from the photo processor, except for a few shots taken by friends and acquaintances, like this black-and-white three-by-five with a dainty white scalloped border. The bride stands in the center, overexposed in her long-sleeved white wedding gown and veil, holding a bouquet that looks like a head of cauliflower. The dress—a lacy, poufy “wedding-cake” number that’s a bit loose around the bodice—is rented. Or was it borrowed? It must have been difficult getting married so far away from home and without the frills or fanfare she might have expected in Taiwan, where she’s the eldest daughter of a well-to-do family. Her attentive, stylish mother surely would have fussed over her, designing the gown and veil herself, hand-making exquisite corsages of silk orchids and peonies, and arranging a ruinously lavish banquet. But in Princeton she’s just another graduate student, working part-time at the library to help support her now-husband, who’s getting his PhD in Biblical Studies from the seminary. The full skirt of her wedding dress spreads airily around her, an illusion of lightness concealing layers of obligation. Her hair is newly cropped in a soft, curly ’do like her mother’s, a privilege reserved for married women in Taiwan. She’s wearing a pearl choker, the only thing she’ll take home at the end of the day. If her mother couldn’t oversee the entire wedding, she would at least make sure that her daughter walked down the aisle with her own jewels, head held high.

Standing next to the bride, the groom is grinning toothily in his square-framed black glasses and dark suit, handsome as a poet. (Is that the same suit he wore when boarding the airplane to go to America, waving like a celebrity to those he left behind?) His hair is still inky black, not yet prematurely gray from burning the midnight oil. His smile is open and candid, while the bride resembles the Mona Lisa, smiling inwardly at some amusing secret. Perhaps she is anticipating the reactions of friends and relatives back in Taiwan when they see the wedding photo: they will shake their heads, amazed at her courage in going away for so long, living among foreigners, eating bland American food, mastering English well enough to get a job, and getting married in such modest circumstances—away from the comforts of family and community, and yet with infinitely more freedom than any of them could possibly imagine.

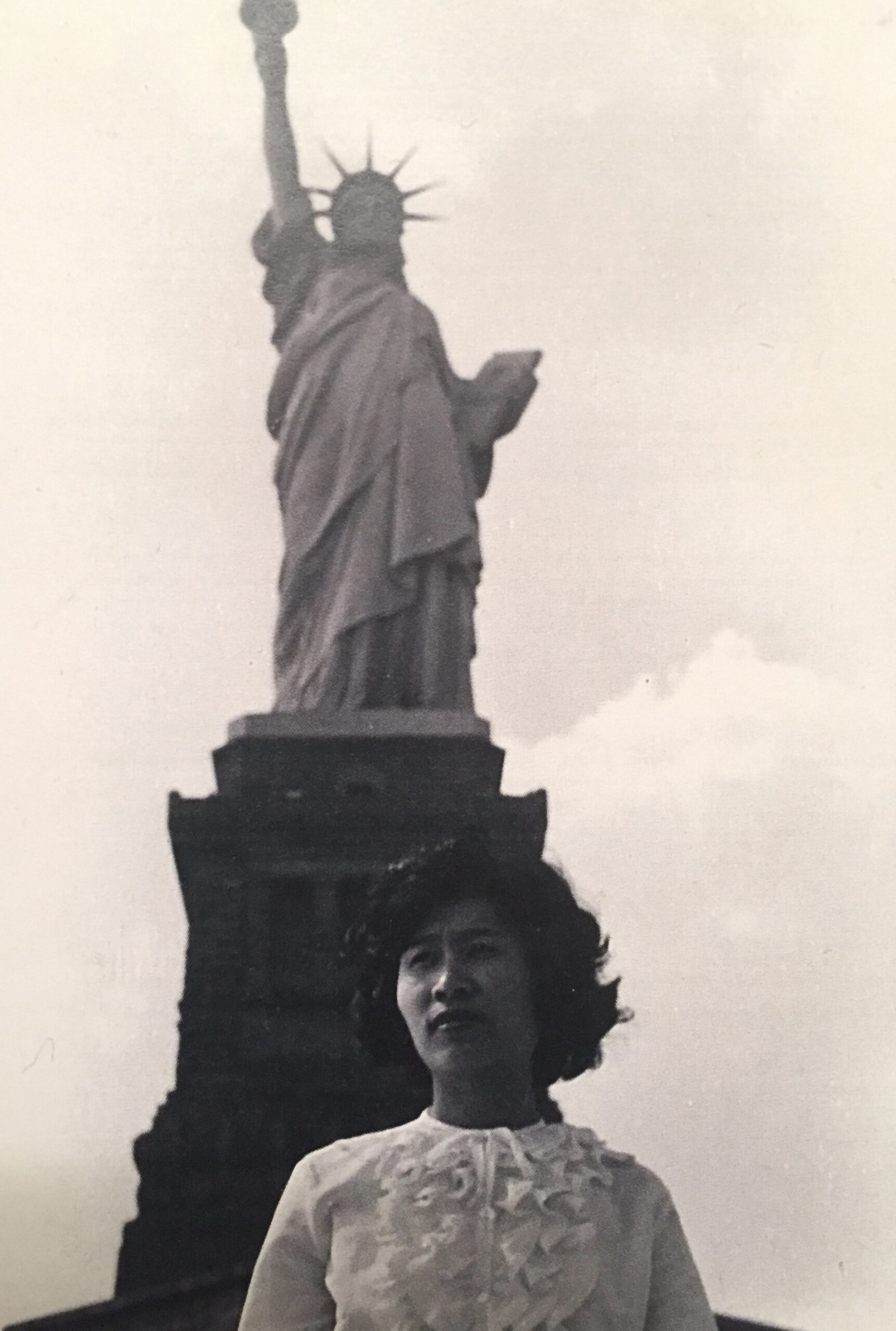

- Liberty (1962)

She stands in front of the Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island, New York. The photo is shot slightly from below to accommodate the massive statue with the spiky crown, monumental arm thrust skyward, torch cut off at the edge of the frame. She is squinting off to one side, the sun highlighting the regal curve of her cheekbone. She’s wearing a long-sleeve white blouse with a wild froth of ruffles cascading from shoulders to mid-chest, and a slender bow tied at her neck. Her hair is chin-length, permed into large springy curls that frame her face, unlike the long, straight tresses she wore in a ponytail or a librarian’s knot when she first arrived in Princeton. This is her new, grown-up, American hairstyle, a transformation she made just before she married her husband. He’s the one taking the picture.

It’s their honeymoon. They are penniless graduate students, so all they can afford is a weekend in New York: the cheapest room at the Empire Hotel, a stroll in Central Park, hotdogs on Coney Island, the ferry to the Statue of Liberty. They spend a grand total of fifty dollars, beyond extravagance, the husband sweating each time he reaches for his wallet. What is she looking at? Her eyes are focused somewhere in the distance, just like the statue in whose shadow she stands, that sentinel of American freedom, patron saint of refugees and seekers, the dark-skinned and tongue-tied. She is not smiling; she seems lost in thought, as if pondering how she came to be situated in this bright, cloudless landscape, breathing in the salty breeze of a different ocean, the starched air of the western world. Why am I here? When will I be able to go home? How will my life be different, now that I’m married? Does my mother miss me as much as I miss her?

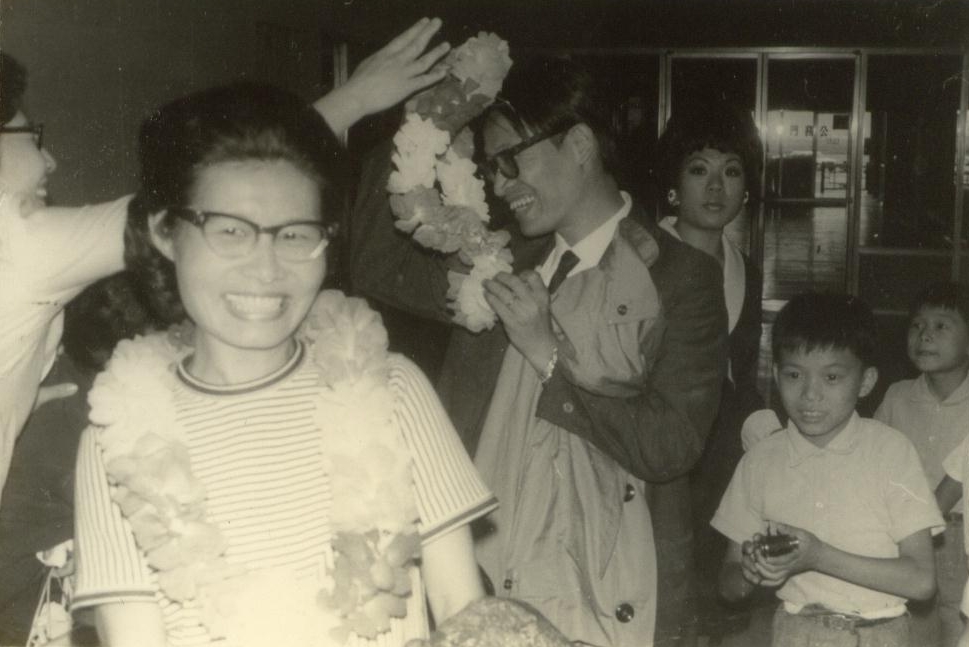

- Homecoming (1968)

The snapshot has a paparazzi feel to it, as though the person holding the camera wanted to capture the exact moment of the couple’s dramatic entrance. Tian-Hiong is in the foreground smiling big, looking like a movie star with her sleek bouffant and horn-rimmed glasses. She looks thinner, more sophisticated, well-worn in a dignified way, like a leather suitcase that’s circled the globe a few times. Behind her, I-Jin looks the same but older, still handsome, with wisps of gray just beginning to show around his temples. He is smiling with his head down as someone throws a lei around his neck. This is the day they have been waiting for—the day they finally came home to Taiwan after nearly a decade studying and working in the United States.

When they left Taiwan ten years ago, they were hopeful college students with little more than a plane ticket and a sense of ambition. Now, they return to their homeland transformed by their accumulated acts of passage: immigration, acculturation, graduate school, first jobs, marriage, and parenthood. They are recognized for the first time as husband and wife, and are proud to introduce the gathered friends and relatives to their precocious three-year-old son Teddy, short for Theodore (“gift of God”). They have an enviable future: I-Jin is a newly minted PhD, and Tian-Hiong, radiant in her happiness, is pregnant with their second child. A girl.

The years of hardship and homesickness are over. They are no longer in transit, no longer just “passing through” until they can make their way home. Now their lives can really begin: they will dedicate themselves to teaching at the seminary and sharing the knowledge they acquired overseas. They will be faithful servants of the church. They will go back to being the good son, the successful daughter, the trusted brother, the clever sister, the respected uncle, the thoughtful aunt. They will raise their children here, surrounded by family and supported by community. This is where they belong.

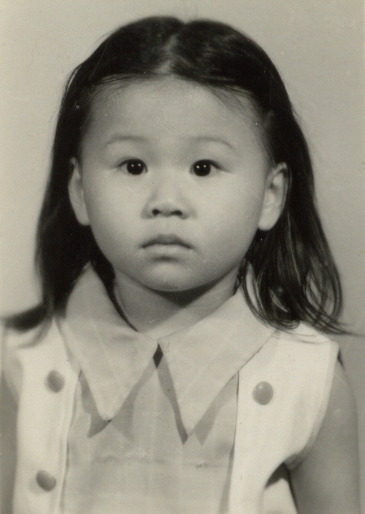

- Passports (1971)

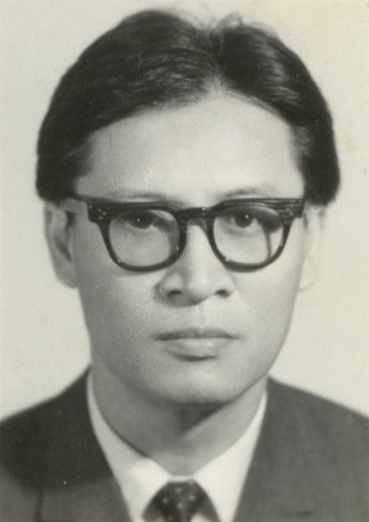

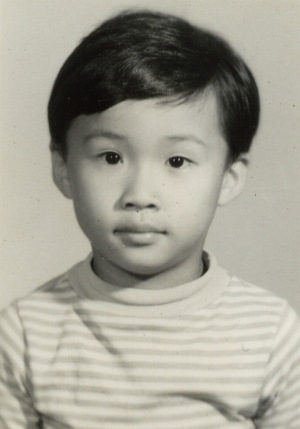

One family, four passports, four tiny black-and-white photos taken in a hurry for an unexpected trip. We didn’t want to leave Taiwan, but we had to.

FATHER. Age 36, clean shaven, black hair combed back, large eyes behind square black glasses. A direct and serious gaze. Regal nose, mouth set in a firm line. Don’t look back; what matters is the future.

MOTHER. Age 36, shoulder length hair pulled back, ends curled up in a flip. Smooth skin, square face. Cat’s eye glasses, brightly patterned dress, a single strand of beads around her neck. This is for the best.

SON. Age 7, hair neatly combed and parted over his left eye, round cheeks, slightly protruding ears. His father’s nose, his mother’s eyes, an American passport. What’s the big deal? Traveling is nothing new.

DAUGHTER. Age 2 and a half, no longer a baby, not quite a toddler. Wispy hair parted in the middle and fastened with two bobby pins. Round face, round eyes. Mommy, Daddy, when are we going home?

*