Special Feature: An Interview with Ayelet Tsabari

The Program in Jewish Culture & Society at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, hosted a fabulous series of creative writers under the heading “21st Century Jewish Writing and the World.” Israeli-Canadian-Yemeni author Ayelet Tsabari (The Best Place on Earth, Random House, 2013) joined us on February 25, 2019, and read from her fascinating and newly published memoir, The Art of Leaving (Random House, 2019). A rapt audience filled Lucy Ellis lounge as Tsbari discussed her life and work with Brett Ashley Kaplan (Director of the Initiative in Holocaust, Genocide, Memory Studies and Professor in Comparative and World Literatures). What follows is the written version of that interview.

author photo by Jonathan Bloom

BK: The Best Place on Earth is a beautiful collection of stories; they are rendered very delicately and you manage to embed the political situation within the narrative of love (whether romantic or filial). I found the stories very moving and they kept coming back to me. Then, you wrote a memoir! How and/or why did you skip, as it were, the novel or several novels that might, in a more typical trajectory, have fallen between short stories and a memoir?

AT: When I started writing in English, writing fiction in my second language seemed inconceivable. It was beyond what I could imagine. Then, I came across creative nonfiction in literary magazines and was blown away by it. The idea of crafting lived experience into a story seemed like the ultimate creative endeavor. Back then everything was translation; I was living in translation, so I fell naturally into that act of translating life into art. There was also something comforting about writing in a new genre: a new genre for a new language, I thought. And I knew I had stories to tell; I lived my life making sure of that! So I started writing anecdotes from my own life, which eventually grew to stories. Only after a year or so of doing that, I wrote my first fiction story in English. By then I was already in love with creative nonfiction. So, while I was always a fiction writer first and foremost, in English, my beginning was tied to CNF. I wrote intermittently in both genres for the first few years, so that by the time I finished The Best Place on Earth, I already had several pieces—essays, short memoir, some of them published— that I could see coming together into a book. It took longer than the short stories to complete, to make sense of them as a whole, to see their thematic thread: I wrote the first essay in the book in 2007 and the last, ten years later. I certainly didn’t skip the novel: I have been working on one for a while. And I intend on writing more short stories. And more essays. I never quite understood that expected trajectory anyway. I like the challenge of new forms and new genres, and I write what I am called to write at any given time. Who knows? Maybe I’ll write poetry next.

BK: In The Art of Leaving the figure of the “freha” haunts the memoir, as if she kept returning and kept being resisted by you as narrator. What motivated the choice to make this concept a central part of the text? Do you see the “freha” as illuminating stereotypes about Mizrahi women? And how do you see the memoir as a whole in terms of the histories of Mizrahi women?

AT: It’s an interesting observation. If it haunts the memoir it’s because it haunted me, in ways I was often unaware of, and yes, I believe it haunts many Mizrahi women and at times, especially when we’re young, can dictate the way we conduct ourselves. It was only when I started allowing myself certain liberties (I speak of that specifically in “A Simple Girl”), like dressing in certain ways or dancing a certain way, that I understood the extent of its impact on me, realized that I’d been working so hard to not be mistaken for a freha, to resist it. So I suppose it is the evidence of this journey that you see in the book. As with everything I write, I wrote the book conscious of Mizrahi women’s underrepresentation and stereotypical portrayal in literature. In a sense, I write for them.

BK: In The Art of Leaving, at one point in your peripatetic life you are given the nickname “Turtle” because you carry your home on your back, as it were. Leaving becomes, as you say, a kind of stability because constant motion takes on a deep familiarity. For Jews in diaspora Israel represents a kind of mythical homecoming, a place of origin and a salvation from genocide; it represents, in fact, an end point and a home. And yet the political situation compounded by the place of Mizrahi Jews renders this home fictive—and you choose to live in Canada. How do you see your private choice to travel and live in many different places alongside this question of Israel as home?

AT: This is what I tried to trace or figure out in the writing of The Art of Leaving and obviously, something I pondered deeply throughout my years of travel. Why is my sense of home so flawed? And is it possibly an Israeli predicament? Because despite the fact that for many Israelis there is no other place, and Israel as a concept is the ultimate homeland, as you said, our sense of home does feel fraught, compromised. It is a home that is always contested, a home with shifting boundaries, a home defined by instability. Then, there is the additional aspect of feeling unrepresented as a Mizrahi woman which further complicates the question. For me there is a third reason for that failed sense of home, and it is my father’s loss when I was nine, at a time (as I say in the book) where he was still my homeland, the answer to where I’m from. And experiencing such profound loss at a young age can shake the foundations of one’s home. That said, I actually live in Israel now, at least for this period of time (I’m trying it out!) Truth is, despite the uncertainty and doubts I’ve had about the place, I kept longing for Israel while I was living away from it, kept writing about it. Not because it’s the mythical homeland for Jews but because it is where my family lives, where my memories live, where my father is buried, and where I have real roots. Of course, I am a bit of an outsider here too, having lived in Canada for twenty years. But still, there’s something wonderful about being near my family and my community and the landscape of my childhood.

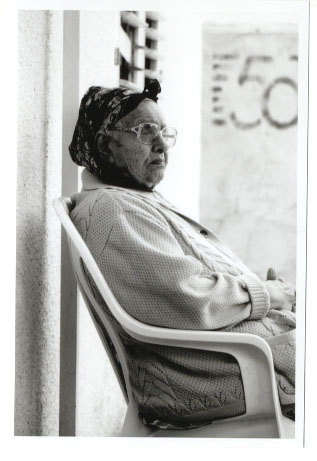

BK: In his novel Deception Philip Roth has his character quip: “I write fiction and I’m told it’s autobiography, I write autobiography and I’m told it’s fiction, so since I’m so dim and they’re so smart, let them decide what it is or it isn’t.” Having written fiction and memoir, are you finding that readers are noting points of comparison between fact and fantasy? In The Best Place on Earth, for example, the story “Invisible” is revealed in the memoir to be about your Yemeni grandmother, who was married at twelve but cared for by her husband who did not consummate the marriage until she was a more appropriate age. The story is told, though, not from the granddaughter’s perspective but rather from the point of view of her caregiver, a mother from the Philippines who has made the achingly painful choice to live so far away from her teenage daughter in order to support her. How do you see the factual within the fictional?

AT: I had a teacher once who said, write fiction that reads like nonfiction, and write nonfiction that reads like fiction. So I’m pleased when people are confused, and they often are. People often assume I am my fictional characters and think my nonfiction stories are fiction. I do approach both genres with a story in mind, with the same emphasis on language, and the same goal of making people feel something. It’s funny, what you said about the grandmother in “Invisible,” because while my grandmother was the inspiration for that story, I don’t see the characters as one and the same. I rarely write autobiographical fiction. I only have a couple stories that are autobiographical, “Warplanes” and “Knives” (which appeared in Tablet). Usually my fiction starts with a scenario taken from my real life, say the situation of a Filipina caretaker and a Yemeni grandma and a young man living in the back (which happened in my own family) but then I let the story take flight.

BK: In that same story, Invisible, an equivalence—or perhaps more accurately a resonance—emerges between the precarity of Rosalynn’s situation as an illegal immigrant and the plight of Jews in German occupied Europe during the war. At one point, fleeing the Israeli immigration authorities, Rosalynn hides in a squalid space under a stairwell—the whole scene echoes hiding from Nazi deportations. It is a powerful and even daring comparison as Rosalynn must make herself as invisible as Satva had. How do you see the situation of illegal immigrants in Israel and elsewhere?

AT: I have to admit that I didn’t see that necessarily when I wrote that, so it’s interesting to hear you say that. Perhaps it was subconscious. The situation of illegal immigrants in Israel is indeed heartbreaking and can feel hopeless, especially in a country already riddled with ethnic tensions. To me, the scene of Rosalynn’s hiding echoed another tragedy, that of the Orphans’ Decree, in which Jewish Yemeni orphans were taken and converted to Islam, and more specifically Savta’s experience and her escape from the authorities as they came to take her.

BK: Like Nabokov, like Conrad, like Beckett, you have chosen to write in a non-native tongue. At one point in The Art of Leaving you note that “some words in the English language just rub me the wrong way.” Have you made a home in English writing? Do you still write in Hebrew?

Tsabari’s grandmother, photo by the author

AT: It is a flawed home but that’s okay. I’ve learned to embrace it about language as I learned to embrace it about place. I don’t expect the wholeness or simplicity that is often associated with the notion of home from either. I accept now that home is a more fluid and complex idea for me, often not a physical space, and I hold on to my family and to writing (in whatever language) to provide me with a sense of home.

I didn’t plan to write in English. It just happened, and I ended up falling in love with it, with the newness of it, the lack of shared history, the anonymity it afforded me. In that sense, it mirrors my experience of migration. I also loved the challenge and learned that I thrive on challenges.

I still write in Hebrew sometimes, when asked, and I find it challenging now too, after being immersed in writing in another language for so long. English informs my Hebrew now similarly to how Hebrew informed my English. It’s all hard work, and that’s fine. Writing is hard. I don’t expect it to be easy. If it were, I’d lose the urgency, the energy, the authenticity, and the uniqueness of my voice.