Mimi Schwartz

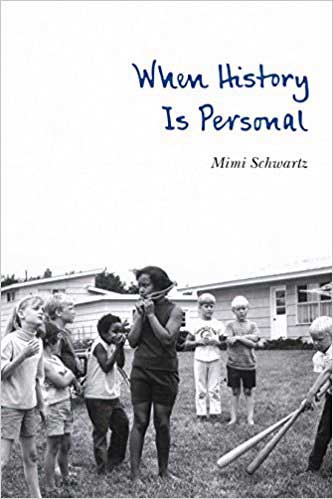

We at Ninth Letter are big fans of the work of Mimi Schwartz, how the clarity of her no-nonsense prose never fails to reveal hidden subtleties and complexities. Her forthcoming collection of essays, When History is Personal (University of Nebraska Press, 2018), further extends the range of her canny artistry. Here Schwartz finds echoes of world and national headlines in the home, and in neighborly and personal relationships, bringing the macro and micro together in intimate ways.

In the essay we feature here, “Close Call,” Mimi Schwartz writes of her experience as a juror for a criminal trial, deliberating with an American cross-section of fellow jurors, ranging from a tattooed cartoonist to a stock broker for Merrill Lynch to a psychologist who boxes as a hobby: “I decide this crazy mix of people—half men, half women, seven white, four African-American, two Hispanic, and one East Asian—will click as the kind of jury I wouldn’t mind if I were on trial. It’s a gut feeling, the same one I have when I walk into a new class and know, within five minutes, whether it will be a good semester or not.”

And what follows is a messy process, filled with sordid details and moral crises, which will make a reader proud of the American system of what we call justice. In these days in our country when the rule of law is being tested as perhaps never before, Mimi Schwartz’s essay can give us hope.

—Philip Graham

Close Call

Last time, I considered myself lucky. I told the judge that I live in Princeton, am a writer and professor, and my mother had been robbed at gunpoint in a parking garage—and heard, “Thank you for your services #6.” End of jury duty. I’d planned to say all that again, but just in case, I ask a friend who is a retired New Jersey prosecutor: “What outfits did you definitely reject in jury selection?” I am thinking high black books, artsy vest, black beret tipped over my eyebrows—something ultraliberal and slightly kooky. “People often call to find out how to avoid jury duty, but you’re the first to ask me what to wear!” She laughs as if I told a bad joke—and gives nothing away. I am clearly on my own.

*

At 8:45 a.m., I huddle with twenty other latecomers under the Juror Shuttle Bus sign in a parking lot that is next to the highway running through Trenton, the state capital. We are young and old, black, white, Asian, Hispanic, fat, thin, running late, and sleepy. Someone says, “It’s not too far to walk,” but no one moves. This group—we hail from nearby suburbs and towns—would rather be late than risk unknown urban streets, even if the sun is out, the air crisp, and we will soon be late.

A white bus with “County Sheriff” printed on its side finally rolls up to drive us through narrow streets with red brick sidewalks, old enough to have been here when Washington crossed the Delaware on Christmas Eve, surprising the drunken Hessian soldiers. That was 1776, and the Battle of Trenton, fought right here, saved our fledgling democracy from King George’s tyranny. Today I see only darkened bars, three men talking at a corner, a few boarded-up stores, and a half-lit diner.

The bus stops at the Mercer County Courthouse, and with juror badges in hand as instructed, we follow the guards, prison-like, up well-worn stone steps, through a security turnstile, down a long hall, and into a cavernous room filled with two hundred other prospective jurors (they’d arrived on time).

A blond woman cheerfully announces “plenty of coffee.” An African-American man dressed in a blue uniform, plays a video about what to expect and how lucky we are to live in a country that has trial by jury. In high school we snickered at such earnestness, but that was the complacent fifties. In today’s uncertain world, I feel a twinge of guilt as I touch my tipped beret and try to ignore an annoying voice in my head: “It’s time to put up or shut up!”

Because, yes, I am one of those who rails every morning at the New York Times’ headlines, Where are the middle-of-the-roaders? Why don’t they stand up to those who usurp decency and respect? I’m loud enough for my husband Stu to wait upstairs until I reach the Style section or Science Tuesday before descending to the kitchen.

My sociologist friend Suzanne likes to say: “The silent majority isn’t called silent for nothing.” A child of 1930s Austria, she worries about rising fascism, as do many I know, myself included, with personal connections to Europe in those years. It could happen here, they warn, and not just to Jews or gays or Jehovah’s Witnesses, but to everyone deemed “Other” by those on a rant that “the real America” is lost.

The real America is in this room. They come in every accent, class, and color, some in suits, some in ripped jeans, one with white vampire nails, many with tattoos, a few in pale silk saris, one in a red print muumuu. We read, talk quietly, text and knit. The young Chinese woman beside me is sewing a Gingerbread Boy potholder. I’m struck by the orderliness and willingness to cooperate, as if what is happening here matters.

The next trial is a criminal trial, the blond woman announces: “So no early dismissal. The judge wants all of you for possible jury selection.” The room is abuzz. What if it is a murder trial? That could mean weeks, or more. Some rush to the clerk’s desk with excuses, and I debate and calculate—Bad back? Surgery? Perjury? But most of us line up, as I do, to climb the stairs to the courtroom. “There is an elevator for those who need it,” says the man in blue uniform, but four flights of steps may well be my exercise for the day.

*

We sit on benches like pews, elbows touching in a stately, wood-paneled courtroom. I’m squeezed between a Skull and Bones T-shirt and an argyle sweater as framed portraits of solemn men in black robes look down from the walls.

“All rise for the judge!” says a booming voice, and a man enters and seats himself on a highly polished wooden throne above us. He has a white beard, round face, and rosy cheeks, and I imagine him saying “Ho, ho, ho!” in other circumstances. But today he is briefing us on the charges: the defendant, a prisoner at Trenton State Prison, is accused of aggravated assault on two prison guards. (The name Trenton State means nothing to me, but it houses the worse of the worst, I find out, post-trial from my prosecutor friend—one of many facts we won’t learn in this courtroom.)

We are handed the Jury Questionnaire, and the judge says he will ask all twenty-eight questions during jury selection and we must pay close attention to everyone’s answers. “So no cell phones, no reading,” the judge says cheerfully. “Otherwise a long process will become a long, long process.” He starts reading and seems in no hurry: “A juror must be eighteen or older, a citizen, able to read and understand English…” I reconsider the possibilities of my bad back: that I will be disabled, sitting for hours on these benches. I imagine everyone else thinking the same thing.

*

I am in seat #13 in the jury box, which is soft-padded at least. My number was among the first called, but dozens have come and gone while I sit here. My funky look isn’t working. Only people in seats #1 and #6 keep being questioned and replaced.

The judge asks everyone: “Is there anything about the length or scheduling of the trial that would interfere with your ability to serve?” The answers come back, “I have a business trip.” Excused. “I have non-refundable cruise tickets for our anniversary.” Excused. “I’m having dental surgery next week.” Excused.

“This judge is really easy,” whispers the guy in seat #12. He’s been beside me for two hours, a churchy type in white shirt and bowtie who, it turns out, writes for the Wall Street Journal. “Last time I sat in a jury box,” he says, “if you told the judge you had a business trip or cruise, he’d tell you to change it. Not this judge.” He is letting anyone with a reasonable excuse go: A mother caring for three young children and a sick mother. Excused. A young man starting a new job who is worried his absence will make a bad first impression. Excused.

I look to see which questions might get me off. Have you or any family member ever been a victim of a crime? Aside from my mom’s mugging, I could mention the thief who swiped my handbag near Macy’s, and the flasher I saw when I was nine, on the corner near PS 3. The police made me come to the station to identify him in a line-up, which I did. I was never sure he did it, or that he’d been locked up, and kept looking for him at that street corner.

Do you think that a police officer is more likely or less likely to tell the truth than any other witness…? At least fifteen people are dismissed on this one, and I, in good conscience, could answer “Less likely” and go home. But when my turn comes, I keep quiet. Five hours into the process, I’ve become hooked on who will stay, who will go, and what will happen next. The shirker has given way to the citizen in me (and the writer easily hooked on stories).

Some dismissals are easy to predict: an unemployed janitor, a guy arrested on a protest march for wearing a mask, a woman whose family are cops, a scary-looking white guy who storms in and storms out. The defense lawyer eliminates the conservatives; the prosecutor, the liberals. And both say goodbye, as one lawyer friend put it, “to all who think too much and think they know too much.” Last time that I was called that meant writers, lawyers, social workers, and professors; but this time we are still here. So is the woman who said her hobby is gambling in Atlantic City and another who, when the judge asked why she’d make a good juror, answered: “God will tell me the truth!”

It’s after five p.m. before we have a full jury, and can’t leave until the judge finishes his instructions: No talking to anyone. No researching this case on the Internet. Remember, “You are the sole judges of the facts!” and must base decisions “only on the testimony of witnesses and on objects that are exhibits admitted in the courtroom.” We are sworn in on the Holy Bible—What about separation of church and state?—and told to report back at 9 a.m. sharp.

*

Thirteen of us sit at a long table in a narrow juror room, waiting for the judge to call us to his courtroom. It’s 9:20 a.m. and #14 is not here yet, so the trial can’t begin. Two of us will be alternates and a lottery will decide, says our guard, but either way, no one is excused from the proceedings, so I’d rather be one of the voting twelve.

I’m next to a white guy, 300 pounds easy, with a dragon tattoo on his forearm and smiley face buttons on his T-shirt. A cartoonist by night, he whips out his cell phone to show me his best character: an orange monster, huge and a little menacing, but something sweet in him too, like this guy. On my other side is a good-looking African-American, studying stock reports. He’s a broker for Merrill Lynch.

Across the table is the insurance claims officer with whom I walked from the parking lot. We both chose fresh air over the juror bus and arrived triumphant with exercise on streets that proved safe. I’d always pictured claims officers as Scrooge, but he is a cherub-faced, young music lover whose girlfriend likes yoga.

Over lunch and during breaks, I talk to the perky Hispanic woman who works in a state office in Trenton, helping the poor get heat. (She’s the one who told the judge her hobby was gambling). A perfectly coiffed woman, African-American, who is a branch manager for Bank of America, is reading George H. W. Bush’s memoir during breaks and recommends it. The born-again Christian divorcee who told the judge, “God will tell me the truth” talks about her new partner, a female corrections officer. The Jewish lawyer, retired from Port Authority, says he would have been in the Twin Towers on 9/11 if Giuliani hadn’t called an uptown meeting that morning. The Protestant psychologist, a single mom with three kids, says she loves her college job in Philadelphia. And my jury box mate, the Wall Street reporter, has left his suit at home and returned in jeans and a sweatshirt. His “outfit” yesterday didn’t work either.

The missing juror, an East Asian woman, arrives fifteen minutes late, saying she had to drop her daughter at school before coming here. “No bathroom breaks for you!” someone calls out in an easy manner that makes her smile. I decide this crazy mix of people—half men, half women, seven white, four African-American, two Hispanic, and one East Asian—will click as the kind of jury I wouldn’t mind if I were on trial. It’s a gut feeling, the same one I have when I walk into a new class and know, within five minutes, whether it will be a good semester or not.

*

Back in jury seat #13, I listen to the judge introduce the defense and prosecution teams. They are all sitting sideways to us, like silhouettes; the judge as well. The prosecutor is the trim white guy in a pinstriped suit next to a big black man with a bouncer’s build. I assume he is the defendant, but he turns out to be the assistant prosecutor. So much for my liberalism, free from bias! The defense lawyer, a young white woman with a brown braid, is next to the defendant, a scrappy-looking white guy in his fifties, staring straight ahead as if catatonic. Maybe it’s because his lawyer is wearing a suit with a mini-mini skirt that ends high on her thighs. All I can see are long, bare legs. Sitting close to a guy from jail?

The prosecutor opens first. He is smooth, practiced, and very high tech. He shows us tons of photos of the prison layout, the five-by-eight-foot cell, the hallway outside the cell, the bolted-down bed and the toilet, which is in the middle of the room, and the cluttered wall-shelf, full of cruddy food. The defense lawyer clutches her notes during her opening statement, stumbling over words. She never looks at us. This must be her first trial.

The judge keeps warning us to pay attention only to admissible courtroom evidence. Here’s what’s presented as fact: The prison guard came to do a routine strip search. Stripping is routine? The prisoner cooperated until the guard decided to search his room for a lid from a soup can, a potentially dangerous weapon. So why are can openers sold in the prison store? The officer asked the inmate to find it, and after a few minutes, he heard, “Find it yourself, asshole!” The officer made him face the wall, and the defendant suddenly swung around and punched him in the shoulder. A second guard came in and both guards fought the inmate, pinning him to the floor in the hallway outside the cell.

I’m on board, mostly, until the first prison guard, Witness #1, is called to the stand. The guy is six feet, weighs 325 pounds and looks like a bully. Why would someone half the size go after this guy? True, the prisoner looks creepy and could have a short fuse if baited. But I need context: Did the guy fight anyone else before? Did the guard have other complaints against him?

Answers keep getting cut off by “Objection” and “Sustained” and endless trips to the “sidebar” where the judge and lawyers keep conferring. It’s as if no one wants us to know who these people were before this moment. I think of the old days of American trials, at least in the Westerns I grew up watching. People knew everyone: the defendant, the family, and the witnesses. Your reputation was on trial with you.

During break, I wonder why there’s a trial at all. The bank manager told me, as we stood in line for the bathroom, that the defendant is not getting out of jail no matter what. I had missed that fact—and am relieved. He’s the kind given wide berth and no eye contact on a New York City subway.

Witness #1 took a seven-month disability leave after the incident to have rotator cuff surgery. From one punch? He probably tripped over the toilet in the middle of the room, and a heavy guy like him would fall hard. He says he never hit the prisoner, and “it was more like wrestling.” He and the other guard needed to maintain order by pinning him down “until reinforcements came.” Really?

The defense lawyer, in cross-examination, makes sure we know that the defendant is five foot eight and reminds the guard that he had been taking Motrin for his shoulder for months before the incident. She shows him the report. “I forgot about that,” he says, his cheeks reddening. Maybe she is cleverer than she appears.

The officer says he doesn’t know what the prisoner’s original crime was—and his whole face turns red. She points out that strip searches are supposed to take place only in the shower room, but doesn’t push it. Still, she is doing better. I’m definitely moving toward a strong “reasonable doubt.” Especially when she asks, “Why didn’t you search for the lid rather than ask the prisoner to do it?” and he answers, “I didn’t want to cut myself.” Baloney.

The prosecutor calls Witness #2, the second guard, and he’s even bigger—six foot three and 347 pounds, the defense attorney slips in. Even a crazy guy wouldn’t assault these two together. This guard looks nicer, not someone who would throw a first punch, more like a follower. He has also been out months on disability, three months for a bum knee. Unrelated, the prosecutor says. Our tax dollars at work? No surprise that his story matches the first guard’s. They’d stand together, one story for two. I guess I should have checked yes on Question #16 about my police bias.

*

The defense lawyer starts Day Two with a bad cold. She spends the judge’s opening remarks sipping a row of tiny paper cups of water and carefully sniffling into fresh Kleenex she keeps taking out of her desk. Pay attention, I want to shout, glad that her legs are in black tights today. Her actions don’t affect the defendant, who sits stone-faced and rigid as before, his eyes straight ahead except for one long glance our way, enough to make me look down, my heart racing.

Another prisoner, two cells away, is called to the stand. A small guy with graying Afro braids, he’s been in this prison forever on five convictions, armed robbery mostly; but I like him better than the defendant. The defense lawyer does well establishing that he uses can lids for ashtrays and chopping tuna fish—and has never been asked about lids or strip-searched. She also lets us know that the photos the prosecutor showed of the cell with the crusted food weren’t of this prisoner’s cell. She is really scoring until she asks, “Do you have any reason to lie?” Even I, who never watches courtroom TV, know better. Objection. Rephrased: “What kind of relationship do you have with the guard?” Does she really think he’ll say, “He stinks!” and return safely to his cell for a long life?

Next is the defendant who, I see, has dark, piercing eyes when he occasionally looks our way. He doesn’t seem stupid. He is like a coiled spring despite a flat voice with no affect, as if he’s on Thorazine. He says he never insulted anyone, never provoked an officer, never hit or made a swing in any way. When they hit him, he just curled up in a fetal position on his bed until he blacked out, woke up, and blacked out again. Somehow, in between, he managed to squeeze out from under these two big guys and into the hall. He could hardly breathe let alone walk. Yet two hours later the video shows him doing both without much trouble.

I am feeling as I did at twenty-three, serving on the only other jury I’ve been on. A boy was on trial for drunk driving: Was he guilty or not? I listened to one side, then the other, and had no idea. Everyone seemed to be lying; everyone seemed to be telling the truth. I can’t even remember the verdict.

*

“This was a cover-up!” says the defense lawyer in closing argument. She has more spirit, more confidence, insisting that the lapses in the defendant’s memory come from the heat of the moment. Who remembers a crisis in exact detail?

I relate to that better than to the prosecutor’s assertion that “any reasonable person would believe the police.” Not these guys. Plus he shows endless photos and a video of the defendant getting off the bed, moving through the hall, etc. It reminds me of students whose papers rely on fancy font to hide lack of content. He doesn’t address what will become a big question later: How a left-handed defendant could punch the guard with his right hand.

The judge, who really seems to want justice to work, takes an hour for his instructions on the law. He reminds us again to judge only the facts and that our verdict must factor in “beyond a reasonable doubt.” And he stresses that we should not be prejudiced against a prisoner because he is a prisoner. We still don’t know what he did or the length of his sentence. The judge spends twenty minutes explaining the charge of aggravated assault: that it must “purposely, knowingly, or recklessly cause bodily harm.” Pain, he emphasizes, is an important component of bodily harm.

*

“There’s no way a five foot eight guy weighing 158 can fight two 300-pounders in a small space,” says the cartoonist. We are back in the jurors’ room, trying to decide what is true. “A right-handed punch from a left-hander just wouldn’t happen!” This from the blond psychologist mom who, it turns out, does boxing as a hobby. The insurance claims guy agrees: “You can’t swing with your left hand and hit a right shoulder when your back is to the wall.” This reminds me of Atticus in To Kill a Mockingbird, arguing that Tom was innocent because he was left-handed. It’s also a common motif in movie and TV trials, so the argument is familiar, and we nod. “Which wall was it?” someone asks, and we look at the photos in evidence. Nothing seems obvious.

The bank manager notes how red the officer’s face got during questioning and how defensive he seemed. The women nod; we notice such things. Except for the born-again Christian who counters: “I got red like that in my divorce proceedings. He was at fault, but I blushed.” She blushes now, holding her ground.

The state worker returns to where we’ve been drifting: “I don’t believe anyone is telling the truth.” Lots of nods now. That’s bad for the prosecutor who argued there was only one Truth, the officers’ truth. The lawyer who worked in the Twin Towers says he has reasonable doubts. “The State did not make its case.” More nods about that. Nobody sympathizes with the prisoner, but where is the case? We should have seen a detailed medical report. The nurse, listed as a witness, was never called. Why not? Was there little bruising or a lot?

We discuss the defense lawyer’s incompetence, how she should have asked more about strip searches. How often are they done? And more about the missing lid. How often does this happen?

We wonder why the judge kept blocking information about the prisoner. Someone mentions reading about a judge in the Midwest who allowed makeup to cover tattoos on the defendant’s face and neck because one was a swastika.

“I don’t think that is fair. The defendant owns it.”

“But he shouldn’t have to incriminate himself.”

“Okay. Then what about a big nose, brown skin, a pregnant belly?

Where does it end?”

We are listening to each other, trying to understand, convince, sort out—and do the right thing. This is democracy at work, what the Battle of Trenton was all about: that the people’s law, not a tyrant, gets to decide. George Washington would be pleased.

Someone asks for an informal reading of how people feel. The foreman, a bland man who got the job because he ended up in jury seat #1, agrees. We go around the table. Everyone feels there is reasonable doubt until we get to the Born-Again divorcee whose new partner is a corrections officer. “I believe the police.”

“Tell us why.”

“These guys are in prison for a reason. You can’t trust them. The officers, work hard, get paid, and hold a steady job. They are the ones to believe.”

Silence. We don’t know what to say. This is exactly what the judge warned against: making judgments because someone is in prison. I mention that, gently. Others second me, softly. But it is the African-American bank manager at the other end of the table who looks directly at her and says firmly: “I think you are being prejudiced.” There are gasps, but also relief at her civil directness. “You said, ‘these guys,’” she continues with no sign of a sneer. “That means you are including everyone in the same category. I think that is prejudice.”

Her words echo a history of racism that still defines the streets we avoid in Trenton. And yet, by being spoken, they move beyond that in this little room. There’s equality here: a black woman is confronting a white woman, without rancor or fear, about justice. And irony too: that the rights of a creepy white prisoner should not be prejudged. The Born Again is taken aback. The two have eye contact, but no darts of anger. She doesn’t answer.

We continue around the table, ending with the foreman who affirms the reasonable doubt argument. What to do now? The lawyer asks the Born Again to say more, defend her position. “I can live with ‘reasonable doubt,’” she whispers. Is it group pressure? The desire to go home? Over lunch, this woman had strong ideas about Cirque du Soleil. “It’s not bells and whistles, just talent,” she said passionately. “Everyone should go and see it.” But she offers no other defense for a guilty verdict—and if she did, would we have listened?

Our verdict is “Not Guilty.” No one is elated, as if we saved an innocent man from injustice. No one liked the guy. But we are collectively pleased with how we worked together as citizens: with civility and in good faith. And we go back to our lives feeling sensible and conscientious.

*

That night I google the defendant’s name, something we couldn’t do before. There he is in a Jersey Shore newspaper, his picture looming. He is a handyman who molested small children in his clients’ homes and posted videos of them on the Internet. I feel soiled, like the crud on the prison shelf. Was this what our twelve citizens contributed to American justice? To judge a child molester innocent? That he stays in jail is not enough comfort. I picture us in the jurors’ room had we known. Reason and sensibility would have been out the window. No wonder the judge held the facts back. He was following Oliver Wendell Holmes assessment: This is a court of law, young man, not a court of justice!

The guards probably knew what the guy did and beat him up, which would make our verdict correct. By law. And maybe we most need The Law for the ugly cases like this one. Old West vigilantism—Just shoot or hang them!—was simpler and cheaper, but “them” were often innocent, the ones powerless and marginalized in a community that didn’t like blacks, Native Americans, drifters, immigrants, mentally disabled, atheists, whoever. Twelve people like us in a jury room were their one defense, preserving, however imperfectly, what Washington fought for down the street—or, rather, fought against: the vagaries of king or mob.

I’m glad I stuck around to sit in jury seat #13. It’s made me value what makes America work that is not in the headlines. I’m even fine, in theory, about voting “Not guilty!” But reasonableness has limits. Then atavism sets in, and the uncivil me has dreams of those guards giving that scumbag a punch for me.

______

Mimi Schwartz’s books include When History Is Personal (2018) from which this essay is excerpted; Good Neighbors, Bad Times: Echoes of My Father’s German Village (2008); Thoughts from a Queen-Sized Bed (2002); and Writing True: The Art and Craft of Creative Nonfiction, co-authored with Sondra Perl. Her short work has appeared in Agni, Creative Nonfiction, The Writer’s Chronicle, Calyx, Prairie Schooner, Tikkun, The New York Times and The Missouri Review, among others. A recipient of a Foreword Book of the Year Award in Memoir and the New Hampshire Outstanding Literary Nonfiction Award, Mimi’s essays have been widely anthologized and ten have been Notables in the Best American Essays Series. She is Professor Emerita in writing at Richard Stockton University.

Mimi Schwartz’s books include When History Is Personal (2018) from which this essay is excerpted; Good Neighbors, Bad Times: Echoes of My Father’s German Village (2008); Thoughts from a Queen-Sized Bed (2002); and Writing True: The Art and Craft of Creative Nonfiction, co-authored with Sondra Perl. Her short work has appeared in Agni, Creative Nonfiction, The Writer’s Chronicle, Calyx, Prairie Schooner, Tikkun, The New York Times and The Missouri Review, among others. A recipient of a Foreword Book of the Year Award in Memoir and the New Hampshire Outstanding Literary Nonfiction Award, Mimi’s essays have been widely anthologized and ten have been Notables in the Best American Essays Series. She is Professor Emerita in writing at Richard Stockton University.

“Close Call” is from When History Is Personal by Mimi Schwartz by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. ©2018 by Mimi Schwartz.