Featured Writer: Annie Penfield

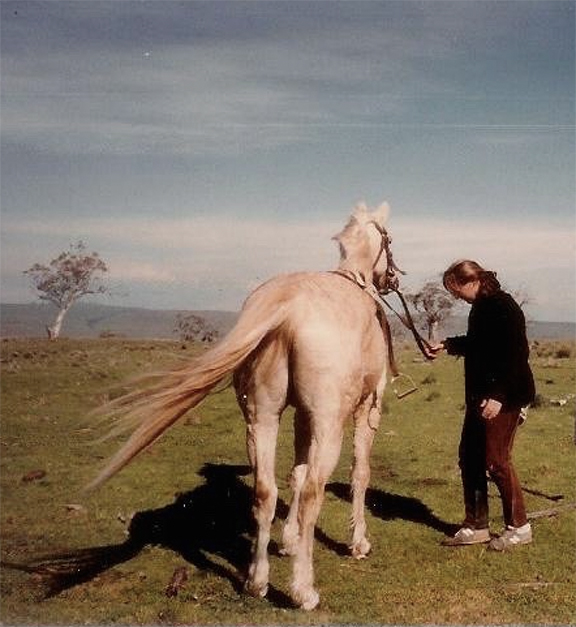

At the age of eighteen, the writer Annie Penfield transplanted herself from the US to a sheep ranch in New South Wales, Australia. There, initially braced only with her knowledge of horse riding, she learned the precarious life of a sheep farm buffeted by the climate pendulum of drought and flooding, by isolation and hard, hard work, and the sometimes surprisingly frail health of sheep. Penfield employs the present tense to recount these distant events, a narrative tactic that allows the past to live again in vibrant remembrance.

—Philip Graham

“Look at the gauge.” Mrs. Bright points at the window, delighted.

Following the direction of her finger, I head to the sink with teapot in hand. Attached to a post outside the house, the rain gauge shows a rainfall of two hundred and fifty points. Beyond the gauge, I see grass sprung by rain, tall enough now to be flattened by rain. And stretching down to the river, a row of waist-high trees that hope to grow to large willows, creating a future avenue, like a grand farm with boughs sweeping over the heads of the next generations. Located as they are near the river, protected as they are within small wire cages, these trees may just survive this drought, now in its fourth year in New South Wales.

The trees are the future here at the Boco Pastoral Company and I wonder if I will be also. I have been working on this sheep station for two months now, having deferred from college and now, embroiled in this family and work, I consider extending my stay. It’s an idea just beginning to rise in my thoughts like the river rising, a new bounty in a dried-up landscape.

The water in the bend of river curves around the house, high enough to see from the kitchen window. The high water reveals a promise that perhaps the drought has broken. I watch the river run as I run water into the kettle.

It’s another day of shearing sheep at Boco and today we muster Teapot: two thousand sheep, two utes, two walkers, two horses, two dogs, and three and a half hours. Michael and I are on horseback. Neighbors Helen and Colin are in one utility truck, and Mr. Bright in the other. My high school friend, Maria, and another traveling worker, Rupert, follow on foot. With so many bodies, we are quick to gather the sheep and move them down to the river. The river is too high to cross so we leave them in Magpie paddock and hope the waters will subside some tomorrow. We have to get them to the yards this week; the shearing team is here now, and we need to keep the sheds full.

*

The next day the river is lower, not as tumultuous brown but still pressing high on the banks. I pull my hat brim down tighter on my forehead to secure my hair out of my eyes. I have left my chaps back at the house. While they had seemed critical when packing my backpack for the journey here and envisioning my life as a jillaroo, I find they are superfluous. They were my resume, but it’s obvious I can ride a horse and help is too in demand to even care how well. And it’s too hot to wear the heavy leather over my jeans. I’m slowly adapting to my surroundings, gathering confidence like sheep to the holding pen.

I pull my legs over the front flaps of the saddle to keep them above the water level as we cross. The river pressing against Pepi’s side pushes his balance and he stumbles for footing. I don’t fuss with his mouth, try to right him or direct him, but allow him to search for footing among the rocks, feel his way with stuttering feet. The power threatens to push us downstream and I am less secure in the saddle without stirrups.

I don’t question the crossing—get the sheep to the yards—at eighteen years old, I follow orders. A job I have learned by Michael’s side through osmosis, through submerging myself in the task at hand. Son of the owners, nineteen-year-old Michael runs this two-thousand-acre station, running five thousand sheep. Today’s task is to cross the river. The dogs make it across, although they float down stream a bit, before pulling themselves to the opposite bank. It’s Michael and I and the dogs across the river with the sheep. Remaining on the yard side of the bank is Mr. Bright, Rupert, Helen and Colin. They will pick up the mob as it emerges and take them down to the yards.

We gallop the valley, soaring the brim, pushing sheep to the water’s edge. It’s like mustering in an amphitheater, with the audience watching from the valley floor. We press sheep to the bank, but they don’t want to go into the water. Their front legs stick in the mud, their haunches pushed by sheep behind. I worry about suffocation as we exert pressure and there is no forward movement. Their hesitation triggers my worry, is the river too great for them? Self-preservation tells them to stay put.

Then one leaps, and they are all leaping, swimming, bobbing in the current. They reach the far bank, front hooves gain purchase in the soft soil and they pull themselves out, water draining from their flanks. Like an overfull sponge, their coats drip as they walk burdened from the river. Sheep continue to pour in and scramble the bank of the far side. Then I see heads breaking from the pack, heading down stream. Lambs. Lambs not great enough to overpower the current only make it halfway before they are overcome. Colin leaps into the river, stumbles through water waist high, catches lambs and tosses them onto the bank. They hit on their sides, find their legs and clamber up to the flock.

Eight hundred get across before Michael and I stagger after them. On the return, I leave my feet in the stirrups, dragging them through water. The bank now treacherous but Pepi is sure-footed as always. I stare down stream. I think Colin got them all.

Helen comes right up to me, “You’re such a natural.” Stunned by the effort, I have no words for her. I have not been pushed across; I have done the pushing. My feet barely wet, but still I feel waterlogged by the effort of compelling such a reluctant mob into a dangerous situation. The work of forcing them into a current that might have carried them away, without anticipating the need to save them, has rendered me quiet. I have not considered consequences. It will take at least a day for this lot to dry out enough to be shorn.

There are plenty of dry sheep still in the yards to shear. Back on dry ground, back into the rhythm of the yards and the steady fall of shorn sheep from the chute out of the shed, Michael and I work together, packing the stripped, svelte bodies into pens. We’re reborn: clean, white, and sleek and ready to move out into greener pastures.

By afternoon, two hundred have been relieved of their heavy fleece. We open the gate from the yards to the first pasture to hold them until we can move them out farther. Released from the yards and the violations to their body, they stream out to grass, their coats now patterned by the ridges of the blade.

Completing this job is relief but the reprieve is dampened by rain. Small drops escalate to a downpour. A four-year drought has a deep thirst and the rain, while boon to the soil is bane to the shorn sheep. This is not the swift current of a deep river, this is just rain. But the sheep no longer have warmth. They look for cover from the rain and in these open pastures nothing can shield them. They scatter like raindrops in the wind instead of finding any comfort in the group.

“Bring them back to the yards,” shouts Michael, rain running off the brim of his hat. Michael understands this quick demise of the sodden sheep and takes action. “We’ll shed them.”

At first, they pour into the yards and then they begin to slow. Sheep that normally scoot from me tuck up and stumble. The rain sucks the life out of them; their whole bodies inhale, sides collapsing inward, ribs surfacing, and they stagger and fall into the mud, slow to rise. I am frantic—as if my will alone can prop them on their feet and move them into the sheds. We push them into the large warehouse. We fear too many packed in may suffocate. Death by warmth seems preferable to me. I am stunned by how the sheep wobble and weaken, but I keep moving.

The yards, unaccustomed to rain, are now mud pits miring sheep. They tip over into the mud and their eye glazes over. I watch them die before my eyes—they have given up. The will to live seeps into the mud. I grab their sides, without fleece there is not much to hold, to get my hands into, but I pull one to standing. If only I can prop her up on her feet, then she will remember life and move and live. I press my knee into a hollowed-out side, pressing in behind her ribs for purchase, and my hand firm on the neck.

I pin her to the side of the shed, her eye the same dull look, and when I release, she crumples back to the ground. She is dying in my hands. Her legs just give way again and again. I want to save her, but she dies at my feet. My fear rises as I lay my hands on another crumbling sheep.

Only 30 points of rain but enough to be a death sentence. We have thirsted for rain. We experience the bounty: water filling the footprint of the Lake, grass springing taller and greener. Greedily we have monitored the rain gauge, the measure of hope, eyed it like the prophet that gives life to the parched, to the deserving. Now abundance runs to saturation, like the sponge that cannot hold anymore. Suddenly there is too much.

Michael alone removes the dozen or so dead sheep from the shed and dumps them in the tip, a ravine away from the sheds that holds the garbage. I wait in his cottage, drying by the fire.

He comes in and sits on the sofa and I move to his side. He doesn’t talk, but pulls a drag on a joint, and then he tells me of his fear.

“I thought we’d lose more. I was scared.”

We are venturing into feelings, new territory, and no longer strangers to each other. What has been playful beginning is no longer a force to be taken lightly. No longer a traveler passing through, I work here, by his side, although I am still eighteen with a plane ticket home. I can’t see where we are going, nor can I anticipate the terrain ahead, so I hunker into the details of this moment. The sadness of the yards clings to me and pricks me like thistles. Holding me in his arms is consolation. Salve to the sadness, he reminds me there is kindness in life. He quenches the powerlessness of the day; he props up my will. Held within the warmth of his arms, I am like the small trees outside the kitchen window, held within their cages so protected, hoping to survive this sadness and grow into this future.

“Stay,” he says to me. I move under his arm, curl into the shape of him. I find purchase here: not swept away by the reckless current of desire. He cradles my whole body with his and holds me through the night.

*

Next morning Michael is sick. He walks slowly to the yards. Both hands on the draft, taking the weight of him, he looks me in the eyes: “You draft,” he says.

“Okay,” I respond. Day after day I have watched him move the gate with precision, ushering sheep to yards with the flick of his arm. It’s just another rhythm I can find if I turn myself over to it. How hard could it be?

Already the sun shines and the ground has converted mud to dust. Dressed in jeans and his sister Deedee’s over-sized sleeveless shirt, armholes gaping, I stand at the end of the draft. I place my hand on the gate. A swing of the gate will channel a ewe right to the pen for shearing, and a swing to the left will send a lamb to a pen for de-tailing and castrating. Sheep run down the channel to me. I focus on the gate. I think to swing in a rhythm like the way I swing to the rhythm of the horse in order to keep with the pace, but this does not begin with a walk, but starts at a gallop.

It’s hard to time the swing. My eye has to be quick to note which sheep left and which sheep right, my action precise to move the gate before the nose of the sheep, and my grip firm on the gate so the sheep don’t knock me away. Sometimes they hesitate. They don’t want to move out into the open. They need a shove by my free hand to move forward. Other times, the sheep manage to jam themselves nearly two abreast and I try to time the gate to divide them. Soon, I am slamming the gate on heads and swearing at the sheep. Clumsy with the gate but I keep a firm grip. I persist. I like the challenge. Michael seems happy to have me drafting so I don’t feel ashamed of my awkwardness—my appreciation for his skill and instinct heightens. I keep swinging, hoping to get better.

Michael’s father blitzes through the pen: “Oh ho! Look at you. I don’t think they would approve of you back in Boston.”

I assume he is referring to my bra visible through the gaping armhole of the shirt and not that I am slamming the gate on the sheep and preparing for castration. He has none of the politeness or reserve to which I am accustomed in my life outside Boston. He knows I submerge in all things foreign. Yet I am not a stranger and more—somehow I have managed to take control of the gate.

He notices and is not afraid to tell me: “I was stirring my coffee this morning and looking out the window and Ho Ho what do I see but you sneaking out of Michael’s cabin.”

Jarred by his observations, I lose my balance and heave the gate: Slam! into the neck of a sheep, penning her to the side of the chute and she pushes in with the lambs. No time to address the mistake because the power of the mob bears down and I have to swing for the next. No time to even look up but that’s fine because I am too embarrassed to look him in the eye. I don’t have a reply for him anyway. I am not asking for permission. Permission would acknowledge I am beholden to the standards of another as if I am seeking approval. No longer tethered to my past, a past wedded to specific standards, I well up out of this place, my identity arising from this moment in time. I don’t have to measure up. At this moment, I have a hand on the gate, an eye for the sheep, and a desire to learn. The only measure here is the rain gauge.

Here I am none of the identities I am at home. I am not playing sports but playing cards; not running meetings but running sheep; not leading but following. I am not valuing the weight of each activity to be sure it will elevate my chance at my future. Like my chaps, I shed what no longer suits me. I want to fill each moment as full as possible with everything I can reach. I am the rain gauge filling with knowledge that falls from these skies—holding it dear—hoping it won’t evaporate. Here, everything is not only in reach but I am holding it—the land, the ranch, the sheep, the man.

The gate: I tighten my hand on the gate.

“Good on you,” he chortles. “Loggy, a word,” he calls as he heads over to Michael.

Loggy is his nickname for Michael: thick as a log. But Michael grounds his vision, works the farm. He monitors the sheep and moves them, trains the dogs, fixes the pumps and puts up the fences. He kills the sheep to hang in the screened locker for the family dinner. Michael does not seem to mind this nickname. In fact I think it relieves him of the expectation of an Oxford education, and he is left exactly where he wants to be: running this property.

*

Next morning Michael is still sick, and the shearers are off because it’s Saturday. I head into the kitchen alone. I pass the red round breakfast table and head to the stove. Not even the table has the shine of the morning yet. I am in the Bright family kitchen, at ease and alone. It’s like Michael’s touch, this solitude. I had not realized until I stood in it, that I crave it.

No sound other than my own: I stand in a box of morning light by the sink. I have never been a morning person. “Good morning sunshine,” my father would chime to my grade-school self in an attempt to lift my gloomy mood as I crawled deeper under the covers to avoid the sunshine he released when he opened the curtains. Yet here in the sunshine in the kitchen at Boco, I am eager to make a start on the day. Alone, this little bit of breathing space, in this moment before conversation begins and space is shared.

Kitchens seem a place of mothers and daughters, of quiet conversations, passing on domestic traditions. Not in my household—my mother and I spent time together on horses. Growing up, my hometown was the site of the United States Equestrian Team and we often took in young women just out of high school perhaps delaying college plans, or recent college graduates, or girls taking the summer to train in the epicenter of the equestrian world. They rose before dawn, trained all day, and I only saw them at dinner, moving through the kitchen to help my mother, who hated to cook, prepare dinner. My mother, scotch in hand, fork in the other, poking something in the oven, usually a steak, while the helper made a salad—salad every night. Now here I am, taking time off before college and standing in another family’s kitchen, filling their teapot. Like my mother, I am not much help with dinner. I pass through the kitchen on my way to the land. I skirt meal duty. Instead of lingering in the kitchen learning domestic traditions, I am out with the men learning about sheep. I set the kettle on the stove.

A hand waves at me through the crack in the door. “Ah, Annie,” Mr. Bright’s voice filters from behind the door.

“Hand me my coffee will you. See it there on the counter.” I look down at the mug next to the stove. Indeed, a full mug, the liquid swirling, steam rising.

“Yes, that’s it there. See it swirling, swirling, just stirred.” Yes I see it swirling, swirling. He has just been in here and he must have moved as quick as his son on the rugby field to be out of here before I saw him, swirling, swirling. And he must be naked to be standing behind a closed door and I have no desire to see that. I pick up the mug and pass it to him, looking intently at it, and avoiding eye contact, and pass the mug safely through the gap in the door.

“Well done. Thank you, Annie. Why don’t we go plant trees later,” and the door slides firmly closed. That did not sound like a question or an invitation—perhaps a command. Still I am honored he brings me into the fold, a place I want to be.

I head to the wall cabinet to grab the box of muesli and a bowl and head to the table just as Maria comes in from the pantry.

“You just missed Mr. Bright,” I tell her.

“Water’s boiling,” she says as she heads to the stove.

*

Mr. Bright and I bounce along in the ute with a small load of saplings in the back. He accelerates up hill and the trees lay flat in the truck bed. Rolling terrain, the land holds very few trees. Until now I have paid more attention to the open spaces and thought of trees as obstacles, now I consider their value.

“In the second year of the drought, when we realized we really were in a drought, we began to plant trees.” Mr. Bright stops the ute and jumps out. With a sapling in hand, he strides up hill. He’s quick, but I knew that already. The ground is spongy under foot.

“There’s a good spring here. It feeds the lake and brings water down to the yards.” Despite all the rain, the spring is more mushy ground than running water. He lays the sapling down and begins to dig. I stand by, watching, nothing in my hands. Other small trees outline this wet zone. Still saplings, they struggle to make a moister climate.

“It’s so important to replenish the land. Lib and I feel very strongly about giving back. Very strongly.” He pats dark soil around the base of the tree. I like to hear him say “Lib” as in partnership out on the land, not his oft-spoken “Womany” of the kitchen. Here among the saplings, with his fingers in the soil of his station, he thrills to farming.

“Look at this grass!” he says and he is down on his knees separating strands of legumes. “It will bring the mix of nitrogen we need to the soil and improve the forage.”

I marvel at the lushness of the vegetation, grown from a partnership and love of this land. Clearly, Mr. and Mrs. Bright have nurtured this farm. Their thoughtful actions and planning have yield results: roots and abundant pastures.

Another stop and he plunges his fingers into the earth: “Look at this soggy earth. Lovely! Years ago this was a lake. It may be soon again!”

Back in the ute, better hustle or I will be walking home. I love to be in his enthusiasm—that I am valuable enough to invest knowledge in. I bloom under his attentions, the conversations about farm practices and imparting knowledge, offering it to me like I am a small tree to grow into something larger than I am in this moment, to grow into this property. Caught in the buoyancy of his knowledge and love of the land, I am an eager student for this information; it satisfies my thirst for this land.

“Here’s a good spot.” He’s out of the ute again, shovel in hand. I watch him plant the tree and I think of Michael. A subdued version of his father but an embodiment of this place in a manner his father never could be. While his father sees the big picture, Michael tends to the details. While his father plants trees like consequences, Michael fences them off to protect them.

All these little trees struggle to send down roots to find a way into the future. All around streams spring to life, lakes gather like lambs, building density. Michael’s father declares the drought is ending. Each rain sends us in circles, “like a chook with its head cut off” to check gauges and streams and the river and the lake. To be part of the abundance, the sheer celebration of the place springing alive, is how my heart feels. Gauging each point of abundance, holding tight to the gate, smelling the rich soil around the future, my senses all engaged: sharp to the potential of this land and my heart listening for my place within it.

A graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA in Writing Program, Annie Penfield’s work has been published in Catamaran Literary Reader, Fourth Genre, Hunger Mountain online, R.K.V.R.Y, Equestrian Quarterly, Assay, Beautiful Things, Prairie Schooner online, and is forthcoming in Under the Gum Tree. She lives in Vermont, with horses and dogs and her husband, and works at her tack shop, Strafford Saddlery. She is working on a narrative based on her essay “The Half-Life,” winner of Fourth Genre’s Steinberg essay prize and a Best American Notable Essay.

A graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA in Writing Program, Annie Penfield’s work has been published in Catamaran Literary Reader, Fourth Genre, Hunger Mountain online, R.K.V.R.Y, Equestrian Quarterly, Assay, Beautiful Things, Prairie Schooner online, and is forthcoming in Under the Gum Tree. She lives in Vermont, with horses and dogs and her husband, and works at her tack shop, Strafford Saddlery. She is working on a narrative based on her essay “The Half-Life,” winner of Fourth Genre’s Steinberg essay prize and a Best American Notable Essay.