my heart. your soul.

A Ninth Letter Pandemic Anthology

Nikki Terry, my heart. your soul. 50×50 oil on canvas, 2018

When I saw artist Nikki Terry’s painting my heart. your soul., I felt it expressed everything Ninth Letter was attempting to convey in this pandemic anthology. While at first glance its stark red colors could serve as an x-ray of this year’s tormented emotional landscape, a closer look reveals a meeting place between heart and soul, a necessary balance, something even calming and redemptive in the midst of trouble. While its essential tenderness is personal (it was created in 2018), Terry’s painting also points to a larger truth for us all: that our need for connection in the face of tribulation can help us make it through.

The various entries in this anthology (including two additional works of art by Nikki Terry) engage with the multiple calamities of 2020 and live for connection. Tabish Khair’s pandemic sonnets reach across the centuries for inspiration, transforming the iambic pentameter of Shakespeare’s love sonnets into the crushing details of our Covid landscape: endangered healthcare workers, the further enriching of the rich during the pandemic, and the inevitably brief resurgence of the natural world as humans hunker down. The hidden story behind James Lu’s account of China’s cynical betrayal of its citizens living abroad during the pandemic is the Chinese people’s hunger for a government they can trust. Gladys Vercammen-Grandjean’s delicate short essay tells us of a Dutch word that has gained a whole new level of meaning during this year’s extended quarantines: “skin-hunger.” Miriam Sagan reports on the roadside memorials—descansos—that have spontaneously appeared in New Mexico in honor of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. Major Jackson’s stunning poem “Eleutheria” asks the question, “How do we know the color of freedom?” and posits a possible answer: “sometimes we call it beauty, we, the martyrs.” The writer William Gillespie offers us a bitterly humorous song, performed by Soda Gun, about socially-distanced romance on Zoom. Michele Morano speaks of an unexpected, fierce revelation during one tentative yet necessary walk outside. Finally, we conclude with a string quartet performing in an opera house in Barcelona, to a full house of seated houseplants: the natural world standing in momentarily for quarantined music lovers.

All the entries here are short, their perspectives meant to serve as quick shards of insight that, together, connect and create this anthology’s kaleidoscopic take on an extraordinary year that is far from over.

—Philip Graham, Editor-at-Large

Quarantined Sonnets

In my second week of the lockdown in Denmark, a friend asked me to look again at Shakespeare’s sonnets for an academic anthology that she was planning. I am a great admirer of the sonnets, and when I started rereading them for the nth time, I also started rewriting them in the present context. As is the case with the original sonnets, my sonnets start lightly, with humor, and end up getting progressively more dark and satirical.

—Tabish Khair

1st Quarantined Sonnet: [Against that Time, if Ever that Time Comes]

Against that time, for soon that time will come,

When I will lie among my own patients

In this room where the ventilators hum

And life’s a rasp of breath, no, not percents;

It clutches, whispers, whimpers, smiles, curses,

It is not numbers, but uncles, grannies,

And looks with hope on us, worn-out nurses

Who rage and struggle, lacking PPEs

Promised by those who campaign or audit!

Against that time, when I will surely lie

In this IC unit where now I sit,

Promise me, promise me that if I die,

They’ll not bury me with praise, as they do:

I want my death to make you angry too.

(The last line of this sonnet is from an essay by Emily Pierskalla, nurse and Minnesota Nurses Association member)

As If It Had Happened Right Here

Personal chapels and roadside shrines mark the landscape of northern New Mexico. Some say that originally its isolation and lack of Catholic priests led to more individualized worship among settlers from Mexico City. The counterculture and an influx of land and eco artists, also influenced the way the landscape is sacralized. Whatever the causes, New Mexico—like Latin America and the Mediterranean—is full of wayside saints.

When George Floyd was murdered, memorials began to spring up in Santa Fe. An ephemeral one appeared in the Railyard—a written piece, some bouquets of flowers. It looked like the work of one—or a few—people. The wind started to take it as we were photographing it.

More permanent was a descanso that appeared on Acequia Madre.

This moving descanso is on the ditch side on Acequia Madre street. A contemporary descanso marks the place of death, such as from a highway accident. Originally these markers showed where the pallbearers had to pause for a rest, putting down the heavy load of the coffin en route to the graveyard. Contemporary ones can also mark a violent and unexpected event that led to death.

This memorial is powerful because no one was literally killed by the police on Santa Fe’s east side. And yet it is as if it had happened right here.

In terms of memorials, sometimes one place stands in for another. After 9/11, the Las Vegas casino New York, New York became a substitute for Manhattan. Thousand of offerings—candles, flowers, gifts—were left there. It was as if a ley line lay between the casino and the island. A ley line of course is imaginary—an alleged energetic connection between places on earth. But like all terraforming, it is a kind of geomancy.

The George Floyd descanso was probably placed by the Mother Ditch because the creator lived nearby. However, the location is also meaningful.

Acequias came from Spain where they were part of the Arabic agricultural systems that shared water in an arid environment. They are communal watercourses. No individual—or city—owns them. Maintenance is collective, overseen by the majordomo of the ditch. In Santa Fe, the Acequia Madre feeds into other smaller ditches. It isn’t used agriculturally any more, but for gardens and to keep the cottonwoods alive. Most farms in northern New Mexico are acequia dependent.

The Acequia Madre is a commons. It is also a vivid reminder that water is life. A shared source of nourishment, it offers hope in contrast to violence, oppression, and death.

The descanso is built to stand, and in New Mexico these memorials are protected, usually kept up, and even decorated seasonally.

Here, a traditional memorial connects us beyond our location, and places us in the whole.

—Text, Miriam Sagan; photos, Richard Feldman

Eleutheria

So little to say of the iridescent grackles

above the courthouse or the architecture

of secrets below like a fragile vocabulary,

or the inundation of idols when winter thawed,

whatever was hidden out of loneliness.

What if we were changed at least once by nights of rain,

by drunken bees in a glade of tufted vetch,

by the fly-tormented psalms of Blake

edging further into the breath of our knowing?

This is a country with a single dream—

all the counties and all the town meetings and all

the demonstrations amount to a sole creation.

Last night I pictured our shadows liberated from human forms.

How do we know the color of freedom?

I’ve a face the shade of maple pressed like an encyclic leaf

in a book from another century no one reads.

I am imagining your fingernails, the great potential

of your profile, how you may never hear the gentlest

parts of my tumbling out of clouds:

sometimes we call it beauty, we, the martyrs.

—Major Jackson

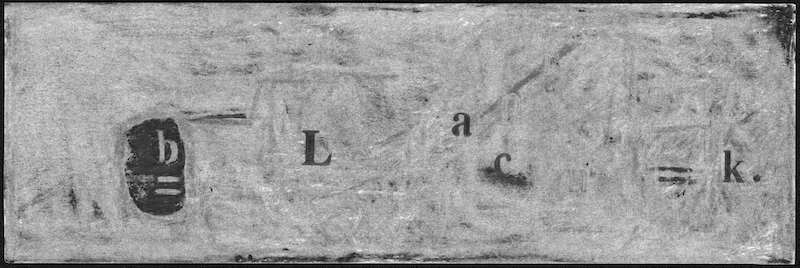

Nikki Terry, black is black. 9×12, crayon, graphite and graphite dust, 2020

Losing Operation Red Sea

In the 1990s the Hollywood film Saving Private Ryan amazed many young Chinese, because of its celebrated story that the US government would send a small troop to save an ordinary soldier from the battlefield during World War II.

In late January of 2020, when the Covid-19 pandemic escalated dangerously across China, the Beijing authorities imposed a virtual lockdown in the entire city. As the pandemic continued to spread, in late February local governments across China launched a compulsory policy to monitor individual citizens’ health status. Citizens were asked to use their WeChat or Alipay apps to report their personal and family members’ health status every day. More than 800 million Chinese have such apps on their phones, so the state could access health information of nearly all Chinese families, pooling it into big data. Equally importantly, because every phone number was linked with its user’s “resident ID card,” through daily smart phone reports the state could accurately monitor everyone’s health. With automatic map positioning, a user could easily be located. In case a person’s health index appeared abnormal and might indicate symptoms of potential Covid-19 infection, or if this person had contacted a Covid-19 patient, he/she would be immediately identified.

Ms. Su is a visiting scholar at a renowned university in the US Midwest, through a scholarship sponsored by the Chinese government. Sending large numbers of faculty to leading universities in the West as visiting scholars is a part of China’s grand project to achieve global recognition for its higher education system. To encourage faculty members to visit foreign institutions, many Chinese universities—including Dr. Su’s—practice a compulsory policy: overseas scholarly experiences are necessary for academic promotion. So in August of 2019 Ms. Su came to the US for her year-long visit, funded by the Chinese government. In late February, when the Covid-19 pandemic began to grip the world, Ms. Su’s home university in Beijing required all faculty and staff members to report personal daily health information via WeChat. Although Ms. Su was visiting in the US, she had to comply with this rule.

In April, Ms. Su’s Chinese university asked its over 50 faculty members who were visiting overseas to join an “Overseas Visiting Faculty’s WeChat Group” organized by the university administration. At that time, the Covid-19 pandemic was coming under control in China, though escalating in both Europe and North America. The campus Ms. Su was visiting had already been closed for three weeks. In this WeChat group, Ms. Su finally felt connected, as she could exchange her concerns with her overseas Chinese colleagues in similar situations strained by the pandemic.

This WeChat group was asked to fill out a form about the plans of their remaining stays overseas as well as their scheduled dates of return. Shortly after the outbreak of Covid-19 in China, most international flights to and from the country had been cancelled. Ms. Su’s scheduled return flight was cancelled in early April. Like many of her colleagues in the WeChat group, Dr. Su had high hopes for submitting this form to the government, which might then arrange additional flights to take them back to China.

Professor Su thought such a scenario was not implausible. Two years earlier, China had released a new film, Operation Red Sea, which served as the country’s answer to America’s Saving Private Ryan. The film told a legendary story of how a Chinese military special task force took on a risky operation to rescue Chinese civilians during the Yemen Civil War in 2015. Operation Red Sea became a blockbuster in 2018, inspiring the country’s pride by demonstrating a Chinese government that, in addition to growing achievements in science, technology and industry, had the benevolence, will and ability to save its citizens beyond national borders.

In the next few weeks Ms. Su’s home institute in Beijing did not provide visiting faculty any follow-ups. Each Monday, their home institute simply asked them to report any changes in their health, and did not answer any inquiries about how faculty might secure a flight back to Beijing.

After waiting anxiously for more than a month, Ms. Su and her colleagues realized they had to rely on themselves. In June, Ms. Su booked an expensive flight with a Korean airline, but it was cancelled two weeks later. After two further weeks of searching, Ms. Su managed to book another flight with a Japanese airline, scheduled for just a few days before the expiration of her visa. The price was almost six times more expensive than tickets before the pandemic.

In order to board the upcoming flight, Ms. Su had been carefully complying with all the rigorous governmental requirements surrounding her health, but soon her dream of rescue was smashed when China announced a cynical new international travel regulation. No passengers, foreign and Chinese citizens alike, would be allowed on board any flights to China unless they could present negative results of nucleic acid amplification testing, a result that is valid for only five days from the time of testing.

In the US, and many European countries as well, requesting a viral test usually has a long waiting time. International travel is not considered the first priority. This policy placed Ms. Su and her Chinese colleagues in a Catch-22 quagmire: if they managed to take their nucleic acid test within five days of their departure dates, they would be unable to receive the results; however, results arriving too soon would be deemed invalid.

The government did not say that overseas Chinese were not welcome to return China. Yet the policy virtually excluded most from returning. The Chinese state has been claiming its success in containing the pandemic, with only a few cases confirmed daily. Most of these cases, the government stresses, were found among international travelers. In publicizing a successful public heath achievement, the Chinese state has never disclosed how it manipulated its international travel policies to prevent large numbers of its overseas citizens from returning to their homeland. Frustration and anger from stranded citizens sometimes circulate in social media within China. Yet such voices are constantly censored. Soon they will disappear in the public media. In the squelching of these disturbing stories of abandoned overseas citizens, the inspiring story of Operation Red Sea will continue to live on as a popular narrative in China, despite the betrayal deemed necessary to effectively control the Covid-19 pandemic at home.

—James Lu

2nd Quarantined Sonnet: [Devouring Time, Blunt thou the Lion’s Paws]

Devouring Virus, pandemic of Greed

Which makes the globe consume its own sweet tail,

Confusing bourgeois want with human need,

Pursuing bootless profit without fail;

O Covid-19 that will kill the old

And poor, the ill, the weak, the marginal,

Though born and bred of Power’s love for gold;

O pet projects of the Neoliberal

In Mandarin Mansion or House of Trump,

For none will forbid them the heinous crime

Of enriching the rich during the slump,

And when the poor have wiped the blood and slime

And promises been made to us in vain,

It will be back to bizness once again.

—Tabish Khair

Skin Hunger

Brussels is a city with the most opaque kissing etiquette. A city where you accidentally snog an Italian because they start on the left cheek and you on the right. A city filled with awkward air bubbles between those who went in for one kiss and those who gambled on two.

I’m missing these confusing yet soft greetings more than ever. The last person I remember cheek-kissing and shoulder-squeezing was my aunt, the night before lockdown. As for touch that stills my skin hunger, my huidhonger, I cannot tell when I started missing that. The absence of skin-on-skin has been consistently present these past few years. Right now, the distinction between abstinence by accident and abstinence by force is at its blurriest.

As a matter of fact, the jerk reaction I currently have when someone stands too close to me in the freezer section, accurately represents how I have been coping with lingering touch for years. I always have to adjust when someone touches me. I crave it, but just as I start relaxing and developing an urge to nest into the other body’s creases, they’re gone.

Touching didn’t always require adjusting. When I was a child, I was a cuddle monster. Arms wide open I’d stand in front of my mother and ask her to “play blanket.” I don’t know when that stopped or why. Puberty, most likely. I wasn’t a difficult teenager. I never slammed doors, but I did close my arms.

The moment I opened them up again and intertwined them with someone else’s is a moment I remember well. Seventeen. Watching an Italian movie that lasted no less than six hours. La Meglio Gioventù. The Best of Youth. From timidly parallel bodies to several points of contact. Chin on head, head on chest, hand in hand, knee over leg. After six hours of Italian drama, finally mouth to mouth. A necessary action, for I stopped breathing several times. Something about a heart in a throat.

From that point on, so many expectations latched themselves onto any bodily contact, surpassing the fleeting hug. Yes, I do want to touch you. Yes, you may touch me. Yes, I might want the touching to increase and spread out. But why so hasty? I don’t know you yet and I’m sure there are movies that last longer than six hours. Or American TV series with too many seasons.

Social distancing has definitely taken spontaneity and hastiness out of dating. It has also subtracted the budding possibility of us.

The last time we met was one of those typical “long time no see” moments. Somewhere along our limited endless conversations, I joke that nothing annoys me more than having to sleep in the same bed as someone else. “When I sleep, everyone needs to stay clear. Way too hot! Way too many body parts in strange angles! I take up the entire mattress, I’m a diagonal starfish.” We laugh loudly.

What I would have loved to tell you is that with you, I don’t need that much space. A single mattress will do, narrower even. I’ll lie on my side, don’t even worry about it. I don’t want to sleep anyway, I want to look and talk and lean and touch and more. Play blanket.

Later that night, you hug me for a long time. I had just told you something sad. I tend to do that, in between the jokes. We’re sitting in the cold on a terrace in Brussels. My last rational thought is that there’s too much coat between us. I’m gently thawing, there in the crease of your arms. And just as I’m ready to be touched, you’re gone.

—Gladys Vercammen-Grandjean

Zoom Boy

(A Covid-19 pop song for your socially-distanced fun)

{mp3}zoomboy|400|{/mp3}

You’re just a face on Zoom

So why do I smell perfume

And know somehow this meeting

Will be fleeting

I’m under quarantine

I’ve got COVID-19

Or something in-between

They can’t tell me

I want to go out tonight

Please can we go out tonight

Would you meet me if I asked

We could both wear medical masks

Or I would happily bask

In your contagion

Even if you only talk about work

Or if you think I’m like kind of a jerk

To see you even six feet away

Would be an occasion

I wanna stay in tonight

Please can we stay in tonight

Meet me alone

In a bio-safety zone

Looking so cute

In that space suit

Though the meeting was wonderfully slow

Boss is fidgeting, it’s time to go

Only a few seconds left

For a private message. . . .

—performed by Soda Gun; song by William Gillespie and Ryan Groff (ASCAP – Perennial Music); lyrics by William Gillespie

Moment to Moment

“Bullyment.” That’s what our son Andrew calls it every day during the latter part of this spring, when we insist he join us for a walk. He’s eleven and would rather stay in his bedroom, playing video games. Half a block from our house, in the park where he used to shoot basketball with guys twice his age, the backboards hang bare. No congregating.

So much was different before the pandemic. Video games in the bedroom, for example. We never allowed that, so he played in communal spaces where we could keep an ear out. But after sixth grade went online and all three of us needed to work on computers, Zooming and recording and just plain concentrating, we had to buy Andrew a desktop and close the doors between us.

That’s not a complaint.

He used to get the school bus at 6:30 a.m. Now, each morning we sleep until we’re no longer tired, anywhere from 6 a.m. to 10 a.m. For a good part of the day we occupy ourselves in separate rooms but come together for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. When he’s bored, Andrew slips into my office and asks, “How’s your life going?” At night we watch movies, work on jigsaw puzzles, read. There is no bedtime.

We’re no longer worried about contagion. Early on, yes, when I had trouble breathing one weekend and on Monday morning Andrew woke with a fever of 102, intense body aches, a headache that made him cry. My doctor gave me a steroid inhaler and his doctor did a flu test (negative), and a week later we were both better. Meanwhile his father, immunocompromised from chronic leukemia, felt fine.

During that time, I woke in the middle of every night, frantic with worry about what would happen to Andrew if his father and I both got sick enough from COVID-19 to be hospitalized. We have no family in Chicago, and how could we ask even our closest friends, with kids of their own and health issues, too, to take in a boy who’d been exposed? I still haven’t solved that dilemma. But after so many weeks at home, weeks of wearing cloth masks in public long before most others did, worry has fallen away.

We know people who are sick, or have been sick, and one who has died. So contagion isn’t an abstraction. And we know that as businesses start opening again, the risks will rise. No one is safe from this virus or from the economic fallout. As professors, we teach from home, but what lies ahead as enrollments shrink and budget gaps grow and talk at universities like ours turns to survival? We’re lucky in so many ways, but for how long? There’s still the leukemia, still the high-risk categories, still the friends and students and family members who are sick or jobless or, worse, who work in health care, their lives at risk every day.

And so, life continues to shrink down to the basics. Each day I tell myself that what we have is all we’ve ever had. Now. Moment to moment. We work separately, eat together, steal breaks in the middle of the day to press cardboard pieces into place, feeling the tiny pleasures of recreating a scene that was once whole. And in the middle of the afternoon, when it’s time for a walk, Andrew comes out of his room, overperforming displeasure and muttering, “Bullyment.”

Throughout our neighborhood, not far from Lake Michigan which is off limits now, tulips stand tall and the pinks and purples of hyacinth seem brighter than in past years. Birds chatter louder in the absence of traffic. In a large bush on one corner, hatchlings peer over the edge of a nest, and after turning that corner we stop, staring hard until the scene ahead becomes clear: On the sidewalk stands a hawk, watching us with a steady gaze, a limp starling at its feet. We whisper and stare until the hawk spreads its wings, grasps the starling in its fierce talons, and ascends to a bare tree limb where, as methodically as I peel carrots for dinner, it plucks the black feathers and tosses them down.

Pay attention, I tell myself yet again, to this terrible, magical time.

—Michele Morano

3rd Quarantined Sonnet: [Tir’d with all these, for Restful Death I cry]

Tired of people, for proper life we prayed,

And then suddenly it happened: a quiet

Fell upon Earth! We saw pollution fade,

And hardly any human was in sight!

At first we hesitated, and then the trees

Filled with birds, the public squares with bird songs:

We occupied the parks! In Jap’nese cities,

The sika deer promenaded in throngs,

And prides of lions settled on Kenyan roads,

And seals on docks, and whales swam close to shore,

And towns belonged to hares, and bears, and goats!

But now this too has passed into our lore:

As chimneys spew poison as in the past,

I tell my pups: it was too good to last.

—Tabish Khair

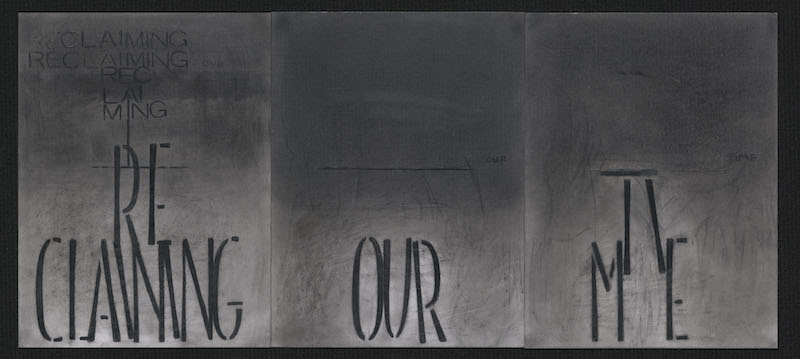

Nikki Terry, reclaiming our time. 24×30, graphite and graphite dust, 2020

Concierto Para el Bioceno

The “Concierto para el bioceno,” was performed on June 22, 2020 in Barcelona’s Gran Teatre del Liceu opera house: a string quartet played Giacomo Puccini’s “Cristiantemi” for over 2,000 houseplants (Puccini was inspired by a yellow chrysanthemum—a christiantemi—to write this short chamber work). Conceptual artist Eugenio Ampudia and Blanca de la Torre, curator of the Galería Max Estrella, collaborated on this event in the hopes that, once the pandemic is over, people will think more deeply about their relationship with nature. Local nurseries provided the plants, and after the performance those plants were donated to healthcare workers in Barcelona.

As of September, Spain is struggling to flatten the curve of an alarming second wave of Covid-19.

String quartet:

Yana Tsanova and Oleg Shport, violin

Claire Bobij, viola

Guillaume Terrail, cello

{vimeo}https://vimeo.com/432544946{/vimeo}

Contributors

William Gillespie is the author of the novel Keyhole Factory.

Ryan Groff is a full-time musician, private lesson teacher, and producer based out of his Champaign studio, Perennial Sound Studio, which has been open since 2012. He’s the singer and guitarist for the band Elsinore, which has spent the last 16 years writing and recording albums, and playing across the US. He enjoys a Midwestern life filled with music and family, splitting his time between the studio and his wife and young children.

Major Jackson is the author of five books of poetry, including The Absurd Man (2020), Roll Deep (2015), Holding Company (2010), Hoops (2006) and Leaving Saturn (2002), which won the Cave Canem Poetry Prize for a first book of poems. His edited volumes include: Best American Poetry 2019, Renga for Obama, and Library of America’s Countee Cullen: Collected Poems. A recipient of fellowships from the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Guggenheim Foundation, National Endowment for the Arts, and the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University, Major Jackson has been awarded a Pushcart Prize, a Whiting Writers’ Award, and has been honored by the Pew Fellowship in the Arts and the Witter Bynner Foundation in conjunction with the Library of Congress. He has published poems and essays in American Poetry Review, Callaloo, The New Yorker, The New York Times Book Review, Paris Review, Ploughshares, Poetry, Tin House, and included in multiple volumes of Best American Poetry. Major Jackson lives in South Burlington, Vermont, where he is the Richard A. Dennis Professor of English and University Distinguished Professor at the University of Vermont. He serves as the Poetry Editor of The Harvard Review.

Tabish Khair is a poet, novelist, and critic who was born in Ranchi and educated up to his Masters in Gaya, a small town in North India. In the 1990s, he worked in Delhi as a staff reporter for The Times of India. Later he did a PhD from Copenhagen University and a DPhil from Aarhus University, Denmark. He now lives in Denmark, where he is Associate Professor in the Department of English at the University of Aarhus. His recent novels include How to Fight Islamist Terror from the Missionary Position (HarperCollins, Interlink and Corsair, 2014), Just Another Jihadi Jane (Penguin/Periscope, 2016; Interlink, 2017) and Night of Happiness (Picador, 2018). Translated into various languages, Khair has won or been shortlisted for major poetry, fiction, and nonfiction prizes in five countries.

James Lu is a writer and researcher with broad interests in Chinese and Asian American cultures.

Michele Morano is the author of the essay collections Like Love (September, 2020) and Grammar Lessons: Translating a Life in Spain. Her short work has appeared in many journals and anthologies, including Best American Essays, Ninth Letter, Fourth Genre, Brevity, and The Normal School. She lives in Chicago, where she teaches in the MA and MFA Programs in Writing and Publishing at DePaul University.

Miriam Sagan is the author of over thirty books of poetry, fiction, and memoir. Her most recent include Bluebeard’s Castle (Red Mountain, 2019) and A Hundred Cups of Coffee (Tres Chicas, 2019). She is a two-time winner of the New Mexico/Arizona Book Awards as well as a recipient of the City of Santa Fe Mayor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts and a New Mexico Literary Arts Gratitude Award.

Nikki Terry is an Expressionist and Minimalist whose paintings build on her personal history, her emotional DNA. The emotional tug of her work she describes as an urgent question, “Can people see my pain, the loneliness? Does it look like theirs?” Working primarily on large canvases, Nikki uses lines to interrupt space and preserve emotion. Her lines, like her memories, are indelible. They are sharp and intrusive, and they appear and recede abruptly. She describes her newest studies of graphite dust on paper as a self-exploration of her “blackness”—“As I smear and press the dust into paper, it feels like I’m grounding down a little more on my identity as a Black woman, a Black artist.” See more of her work at nikkiterry.com.

Gladys Vercammen-Grandjean: Although raised bilingually in Dutch and French, Gladys (BE, 1990) tends to express her feelings best in English. Then again, the many sentences written in her head have a hard time making it to paper. This is her first publication. A graduate in French and German literature and linguistics, Gladys is currently based in Brussels, working in the local museum scene. She’s a constant work in progress, but the people around her, friends and strangers alike, make life utterly fascinating.