Baltazar Lopes

“As if listening to a very sad melody, I recall the little house in Caleijão where I was born.”

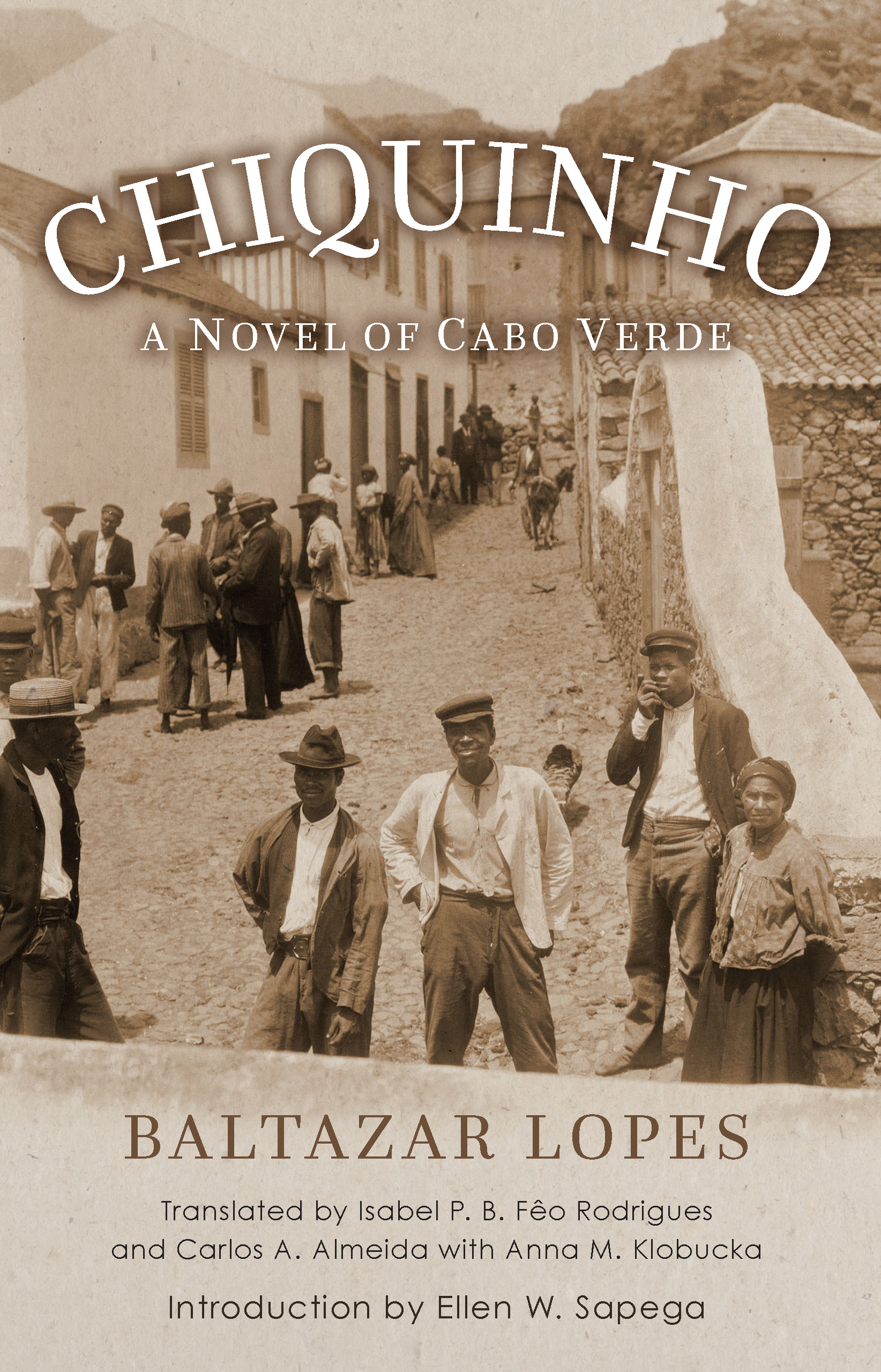

So begins Chiquinho, written by Baltazar Lopes in the 1930s, the first Cabo Verdean novel. Ninth Letter is proud to publish an excerpt from this first English translation of a major African novel, newly published by Tagus Press/University of Massachusetts Press.

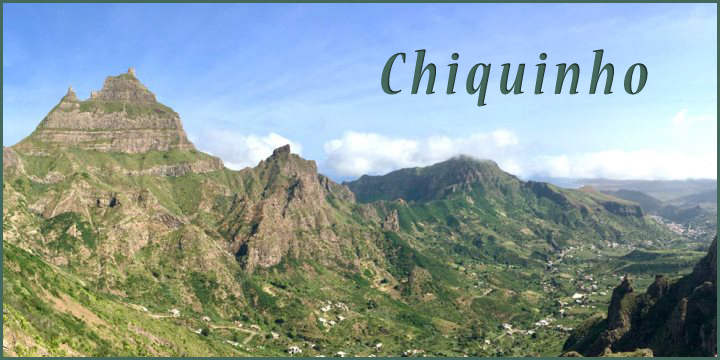

For any readers unfamiliar with Cabo Verde, it is an African nation of ten islands located in the Atlantic Ocean, 300 miles west of Senegal. Uninhabited when they were encountered by the Portuguese in 1456, the islands were eventually peopled by kidnapped and enslaved Africans, Sephardic Jews escaping from the Inquisition, and Christian European populations primarily from Portugal, as well as Italy, France and England. A Portuguese colony for over 500 years before independence in 1975, the majority of Cabo Verde’s citizens are of mixed African and European descent, creating a distinctive “mestiço” culture of great vibrancy that continues to thrive despite the challenges of the archipelago’s geographic isolation and periodic devastating droughts.

Baltazar Lopes’s novel, based loosely on his own childhood and young adulthood on the islands of São Nicolau and São Vicente in Cabo Verde, follows the main character Chiquinho’s journey of self-discovery. Chiquinho could be called the Cabo Verdean A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. But just as important, the novel chronicles Chiquinho’s political awakening and deepening appreciation of the culture in which he grew up. As the translators Isabel P. B. Fêo Rodrigues and Carlos A. Almeida write, “Chiquinho remains a founding novel of an emergent Cabo Verdean literature, in part, because it consciously turned to its own people and region to write them out of colonial oblivion.”

In the following excerpt, we see Chiquinho as a young boy, in love with the storytelling abilities of his elders gathered together in the evening. “Their talents were so extraordinary that the events they narrated came to life in front of us,” Chiquinho says. With the sudden announcement that a woman, Bibia Luduvina, has become possessed in a nearby town, the elders at first turn to exchanging tales of a wandering ghost. When the group finally heads off to attend the exorcism, Chiquinho sees, to his terror, a story much like those he had been listening to, but one that truly comes to life.

—Philip Graham

Bibia Ludovina became possessed. Pedro Xamento delivered the news right after supper, when I and all the other kids were hanging around at Água-do-Canal, listening to the grown-ups chat. Bibia had been doing the laundry when suddenly she stopped, started flailing her arms, and screamed. She was only able to say that they wanted to kill her.

“Is she really possessed?” asked Nha Rosa Calita doubtfully.

Pedro Xamento confirmed. It was really a spirit, he was as sure of that as he was of being his mother’s son. The voice that spoke through Bibia was not hers. It was a deep male voice, and it sounded angry, like a sea captain. Nhô João Joana backed up Pedro Xamento. He had just arrived from Bibia’s house and was spreading the news:

“A bad spirit is oppressing Bibia Ludovina.”

“Explain how it happened…”

“Can’t you see, people? When a body dies with an unfulfilled promise or unexpiated guilt, the troubled soul has to keep returning to earth.”

“Fina Canda died possessed,” reminded Nha Rosa. “Her dead husband, God bless his soul, noticed that when Fina died, a big white bird carried her soul away.”

Nhô João Joana, who knew how to exorcize spirits, explained:

“Every creature’s life is a struggle between the spirit and the body. Evil spirits bewitched Bibia Ludovina’s body.”

They asked him for details.

“This spirit oppressing Bibia is no joke. He only wants to scream and scold everyone.”

The conversation turned to a subject matter that caught my interest—wandering souls. Not that I was fearless, on the contrary, I felt very afraid whenever I heard stories about the dead. But the unknown world that these stories revealed attracted me with its sinister images of dragging chains, anguished screams, cries in the middle of the night, begging for prayers. They started talking about an old ruined house at Salto. Even in the memories of the oldest people, it had always been abandoned, its wooden roof tiles flying off with the wind and its walls covered with climbing São Caetano vines during the rainy season. They told such horrible stories about the house that my greatest desire was to see it for myself. Once, when Pitra Marguida was going to Juncalinho, I went with him with the sole purpose of checking it out. I even dreamed about it. In my dream, the haunted house assumed gigantic proportions and the holes in its roof became black, scary eyes. It moved in my direction, a monster the size of a mountain. I wanted to run away, but my legs wouldn’t move, disobeying my desire to escape the terrifying embrace. The giant figure kept coming closer. I could feel the monster’s breath brushing against my face like sandpaper and its arched arms touching me. As soon as I felt the touch, I screamed. I woke up terrified. I covered my head and prayed an Our Father and Hail Mary.

Nhô João shared what he knew about the house. It used to belong to old Zeferino, a slave ship captain who made a fortune selling black people in Cabo Verde and other places. The oldest folks told stories about the terrible things he did to the enslaved. He was lawless and godless, a heretical creature who did not even know how to cross himself. Surely the Dirty One took hold of his soul as soon as he died. And the soul wandered around restlessly during long nights, haunting the land with its cries and the jangling of slave chains. People say that the soul of old Zeferino is still around, searching for the lost treasure of many gold pieces that he buried somewhere in a clay pot from Boa Vista.

Chico Zepa did not believe in any of these tales about Captain Zeferino’s soul wandering around the world for more than one hundred years after his death. Nhô Chic’Ana assured us they were true. He had seen Zeferino’s soul. He was a tall figure wrapped in a large white sheet. On his head, he wore a big hat with a wide brim that covered most of his face. You could only see the tip of his nose, partly bitten off, and his rotten teeth exposed in a frightful smile. Nhô Chic’Ana saw the captain once, when the night caught him by surprise on his way back from Juncalinho to Morro Brás. There, in that middle of nowhere, when the sun shines on the ocean and night has fallen on the land. Darkness suddenly enveloped him. Passing by the haunted house, he heard agonizing moans and then saw the figure of Captain Zeferino emerge from within the walls. He walked bent over, as if carrying a heavy load. Nhô Chic’Ana froze, unable to take a step. The ghost passed by very close to him. When he realized what he had seen, Nhô Chic’Ana started running like a wild horse.

Chico Zepa’s skepticism was unmoved by the old man’s story. Nha Rosa Calita confirmed:

“Nhô Mané de Ramos read in the Lunário Perpétuo that the treasure exists and will be found by a child born with two teeth when a rooster with ruffled feathers crows for the first time.”

“The Lunário turned Nhô Mané Ramos’s mind upside down.”

“It did no such thing… You’re a heretic. You wish you had in your head half the intelligence that Nhô Mané has in the tip of his pinky.”

“The deceased are sentenced to undo the evil they left behind in this world. Old Zeferino’s money was earned from selling the children of others. They say that even after his treasure is discovered, his soul still has to go around for another seven years dividing the money among the poor. If he doesn’t share it, he will remain a ghost forever.”

“If you see the captain’s soul, remind him that Chico Zepa is one of the poor so he doesn’t forget me…”

Pedro Xamento jumped in:

“If you want money, earn it working under the sun like everyone else. God’s charity was not meant for lazy people.”

“Who asked you to stick your nose into this? Who are you calling lazy, you son of forty fathers plus a few who were just passing by?”

“People! You are my witnesses that Chico Zepa insulted my mother!”

“Call her then to come defend you…”

“You better watch out, Chico Zepa!”

“If you’re really a man, go for it.” Pedro Xamento launched himself against his enemy. But Pedro only had strength, while Chico was agile and good at tripping up his adversaries. He jumped on Pedro’s back and threw him to the ground. The fight expanded, and nearly everyone was angry at Chico. In the end, they were all beating each other up, having forgotten what got them fighting in the first place. At last, Nhô João Joana’s authority was able to calm them down. Chico Zepa was all full of himself, bragging:

“Try me any time you want. My right hand will send you to the graveyard, my left to the hospital!”

Nha Rosa Calita recalled an event from her childhood. She asked Nhô João:

“Do you remember Fina Canda’s story?”

“Fina Canda? I don’t remember…”

“Fina Canda, a very white girl, the daughter of Nha Canda Marguida from Pombas. They lived near Fundo de Balanta, close to Dr. Júlio’s house, by his sugarcane mill. Don’t you remember?”

Nhô João did remember:

“Oh yes, Fina, a girl who looked like a model. Now I remember her very well. She was quite a piece of white-dove meat. They say Mr. Pina was crazy about her. He even wanted to set up a place for her, but they say that when his wife found out, she went to Nhô André Crioulo and asked him to put a spell on her husband.”

“That’s it, exactly. There was no one like Nhô André Crioulo to concoct spells and remedies, using just herbs and prayers in a language that only he understood. It was Nhô André who cured José Capado’s bad wound.”

The conversation of the two old folks digressed from the present case of Bibia Ludovina and plunged deep into the memories of their youth. We listened attentively, absorbed in the tales the old people told. I used to drop everything to listen to them. The days I knew they were going to be at Água-do-Canal after supper, I would swallow the cachupa in a hurry and wouldn’t calm down until I was on the road to Combota. Mamãe-Velha always fought me on this. My grandmother didn’t understand that the stories told by her, Nha Rosa, Nhô Chic’Ana, and the other elders, full of life experience, were shaping my young soul. Their talents as storytellers were so extraordinary that the events they narrated came to life right in front of us.

They told the story of José Capado. He was a married man whose wife was a very jealous woman. He was having an affair with Maria Guida from Fontaínhas. His wife tried everything to separate them, but to no avail. Nhô José was really bewitched by Maria Guida. His wife finally came up with a terrible remedy. One day, when Maria Guida went to town, she gave her husband a sleep-inducing herbal concoction, which knocked him out like a dead man. She then sent for her rival, claiming she had an important matter to discuss with her. Maria Guida, in all her innocence, came by. The wife received her courteously and served her coffee and cuscús. After a while, Maria Guida asked why she had been summoned.

“Wait here for just a moment…”

The wife went into the room where her husband was sleeping like a dead person. She pulled his pants down and castrated him. She then called Maria Guida into the room. She showed her the husband all covered in blood, and told her:

“Go ahead now, you can take this for your lover.”

And turning to Nhô José, who was writhing in pain:

“Kekeke! A castrated rooster can’t fool around anymore!”

Maria Guida fainted and fell on the ground, foaming at the mouth. All of Estância was in shock. The wound took a long time to heal. Nhô André Crioulo finally cured it with a plaster of herbs pounded together with some hair from Maria Guida’s armpit. Nhô José Capado’s wife was sentenced to a year exile on the coast of Africa.

We asked old Calita to tell us Fina Canda’s story. It was a tale about spirits, with all the usual details: speaking in a strange voice, screams, requests for prayers to fulfill promises left unkept by death.

In these conversations, death was always present, walking with us shoulder to shoulder. All the departed had the same tastes and the same needs as the living. We conceived death as another life, similar to this one. Thus our destiny beyond the grave lost some of its mystery. Each one of us was perfectly able to imagine what they would do after death—the loves, the hatreds, and the friendships.

Nhô Roberto Tomásia arrived gasping for air and calling Nhô João Joana. Bibia Ludovina had become more agitated and wouldn’t give anyone a break. Nhô João should go there to exorcise her with his prayers. And some strong young men as well, to hold her down. I joined them to witness the events. We were still far from her house when we heard Bibia Ludovina’s screaming through the night. She shouted and shouted:

“Don’t kill me, don’t kill me!”

Bibia’s tormented cries still ring in my ears: “Don’t kill me, don’t kill me!” Then she burst into a frightening laughter, which hurt me like a newly sharpened knife. It felt as if an army of demons were inside me cutting my soul into pieces. Filled with fear, I shrunk closer to my companions. But I wasn’t afraid of the soul that had possessed Bibia. My instinct told me that the spirit wanted Bibia and no one else. I was afraid of her cries and laughs piercing through the night. I murmured a prayer. When I walked by the shadow of a bush, I made the sign of the cross. And Bibia Ludovina kept screaming. The only reality of that night were those shouts and those bursts of laughter. They were a vivid presence in the darkness:

“Don’t kill me, don’t kill me!”

And the sinister, prolonged bursts of laughter followed, as if from the throats of demons. A shooting star drew a line in the night sky. I took refuge in prayer. Hail Mary, full of grace! The crew was walking in a deep silence. Between the shouts and the laughter, one could only hear the chirping of crickets. Not even Chico Zepa dared to tell his usual jokes. Bibia Ludovina’s shouts touched our souls. When we arrived close to her house, Nhô João started to pray Hail Marys. And the others responded in chorus—“Holy Mary, Mother of God”—like in the rosary prayer of the Divine Mercy.

Bibia was completely deranged. One could hardly recognize her. Her features were twisted into horrendous grimaces. Her mouth was an open gash that curved to the right side. Her eyes had a frenzied expression. She could only scream and shake. Two men could barely hold her. They pinned down her arms and legs, but her body still shook in convulsive tremors. Suddenly, she surprised the men with a jerking movement. Her body curved into an arch, with her belly sticking up. In those moments, she would become silent, shutting her mouth and grinding her teeth. Two women were trying to prevent her from clenching her fingers. She then came to her senses, only to start shaking her body again. And the sound of her screams kept cutting into my soul. It seemed to me that from her laughter issued a gang of demons about to devour me. I felt a desperate desire to run away. But fright kept me paralyzed. I didn’t have the courage to walk back by myself, followed all the way home by Bibia Ludovina’s laughter.

When she saw the crowd coming in, she shouted:

“What are you all doing here? Back off! Get out, all of you! You’re coming to kill me! I don’t want you to kill me!”

Her gaze became even more deranged. Then her voice weakened and she begged again:

“Don’t kill me, don’t kill me!”

Nhô João Joana went towards Bibia. He shouted commandingly:

“For God’s sake, who are you?”

Bibia laughed mockingly, tilting her head backwards. Nhô João demanded:

“In the name of God, Our Lord Jesus Christ, who came to Earth to redeem and save us, I order you to tell me who you are!”

“You want to know who I am? You’ll have to keep wondering…”

Nhô João summoned us:

“Concentrate and say two Hail Marys and two Our Fathers for the relief of suffering souls.”

The whole circle quieted down in prayer.

“Now, Credo and Gloria Patri for the souls in purgatory!”

Nhô João stood in the middle of the room, his head bowed in prayer. Bibia calmed down. Suddenly she started to gasp for breath.

“You are very tired. It seems that you had a long journey.”

“I’m coming from far away…I’m tired and I want to go to sleep.”

“Where?”

“I don’t know. I haven’t rested in a long time. I’ve been wandering around the world like a fatherless child.”

“By the mercy of the Lord of Life and Death, you will rest in the glory of paradise…”

“My place is in hell!”

And Bibia started screaming:

“I want to go away! I want to go away!”

“Go! Who’s preventing you?”

“I’m going, but I have to bring Bibia with me!”

“Ah, that you cannot do.”

“I want to bring Bibia!”

“In God’s name, you’re not taking her. Bibia belongs with the living, and you’re of the otherworld.”

Nhô João grabbed Bibia’s little finger and twisted it until it nearly broke. They placed a clay pot on Bibia’s head. They sat her on a mortar. We prayed. Nhô João Joana inquired some more:

“For God’s sake, who are you? What do you want from the living?”

Bibia was less agitated now.

“I am António Carrinho…”

And the ghost explained that he was António Carrinho. He had left São Nicolau on a whaling ship. After six months at sea, they docked in Dominica. He befriended some locals and went drinking with them. Then, because of some intrigue about women, one of the men slashed his throat. He died, leaving an unfulfilled promise, made when he was sick with a bad fever that he would go around the town’s church on his knees with a candle in his hand. He was returning now to ask them to pray for his soul’s rest and the forgiveness of his unkept promise.

Bibia started to shout again:

“Don’t kill me, don’t kill me!”

She really looked like someone confronted with death that shone at the tip of a razor blade. She stretched her arms before her to prevent something from approaching her.

Nha Rosa Calita was leaving. I took the opportunity to go with her. I rushed outside like someone leaving a prison. The fresh air cheered me up a bit, but walking home I could still hear Bibia’s shouting. All night long that scream was pounding in my ears:

“Don’t kill me, don’t kill me!”

I dreamed that four black men, dark as coal, were coming toward me with open razor blades and were going to kill me. But they all had the same face as Bibia, just as I saw her that night, with her twisted mouth and tormented gaze. When they came close to me, their sudden laughter was so loud that it seemed to be coming from the bottom of hell. I wanted to scream, but my throat was constricted. I could only beg:

“Don’t kill me, don’t kill me!”

Baltazar Lopes de Silva was born in 1907 in Caleijáo, São Nicolau, Cabo Verde, and died in Lisbon, Portugal in 1989. He studied at the Seminary High School in Vila da Ribeira Brava, Sáo Nicolau, and at the Liceu Gil Eanes in Mindelo, Sáo Vicente. He graduated from the University of Lisbon with degrees in law and Romance philology. Upon returning to Cabo Verde, he was professor and rector for more than fifty years at the Liceu Gil Eanes in Mindelo. Lopes co-founded and contributed to the seminal literary review Claridade. He published the novel Chiquinho, as well as a collection of poems, Cântico da manhã futura, and a short story collection, Os trabalhos e os dias.

Translators:

Isabel P.B. Fêo Rodrigues is a professor of anthropology at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth. Her research and publications focus on the ethnohistorical processes of cultural and linguistic change, gender, race, colonialism and creolization in the Lusophone Afro-Atlantic. She has conducted archival and ethnographic research in Cabo Verde, Portugal, and Brazil.

Carlos A. Almeida is an associate professor of Portuguese and the director of Luso Centro at Bristol Community College, and visiting lecturer at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth. He specializes in Portuguese and Cabo Verdean languages, literatures, and cultures.

Anna M. Klobucka is a professor of Portuguese and women’s and gender studies at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth. She is the author or editor of several books and co-translator of Isabel Figueiredo’s Notebook of Colonial Memories.