A Book You May Have Missed:

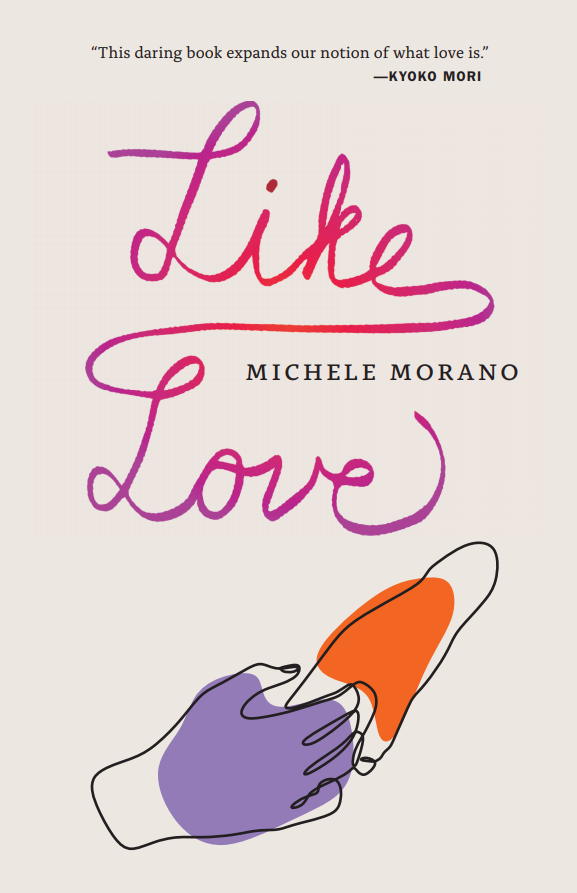

Michele Morano’s Like Love

We at Ninth Letter are great fans of Michele Morano’s writing. We’ve published her essay “Crushed” (8:2, Fall/Winter 2011-12) and her short story “My Mother Was a Beauty Queen” (13:1, Spring/Summer 2016), and most recently, her short essay “Moment to Moment” in our web anthology about the coronavirus pandemic, “my heart. your soul”.

So we’re happy to do a little cheerleading about Morano’s latest book, Like Love, especially since this collection of essays includes “Crushed.” Like Love was published in September of 2020, in the middle of the overwhelming distraction of this year’s pandemic. Why not, we thought, give this excellent book a hearty shout out, for any readers who may have missed it?

Philip Graham: Your first book, Grammar Lessons, was a collection of travel essays about your year living in Spain. Like Love, I think, could be considered a travel book too, but one that explores interior landscapes. But it’s a very specific landscape you examine.

Michele Morano: Yes, I agree. Like Love explores the landscape of unconsummated romance, including crushes and infatuations, the eros of teaching and learning, the romance of parenting, and of course the encounters that happen during literal travel, when one is unmoored from the daily routines of life and experiencing heightened senses because of that. I also think of this as a “coming of ages” book, since it tracks various stages of “becoming” well into adulthood.

PG: Let’s talk about one of the essays in Like Love, “Crushed,” which Ninth Letter published back in 2009. This is such a brave essay. You go where others won’t dare—in this case, the crush that can simmer between teacher and student. The crush, of course, is chaste, yet most people would keep such feelings secret, let alone write about them. And you manage to do this without being creepy.

MM: That was the challenge of this piece, to tell the truth about emotions that make people nervous. Mary Kay Letourneau—the infamous teacher who took up with her sixth-grade student, had children with him, went to prison for it—was very much in my mind as I wrote this piece, because I thought readers might liken me to her. But I’ve never understood her behavior. My first crush on a student developed when I was a twenty-four-year-old teaching assistant, and although the student was super mature and sweet and solicitous enough to make me think he had a crush on me as well, I couldn’t imagine dating him because he was only eighteen. The distance between us seemed cavernous, not just in years but in experience. I don’t understand how a woman in her thirties could ignore an even greater distance between herself and a literal child.

And yet, I’d had a real crush on a twelve-year-old and wanted to explore that. To ask the implicit question: if one isn’t actually a pedophile and doesn’t truly want to act on an inappropriate crush, what does desire mean in that situation? How can we understand it, rather than simply turning away in shame? Those are the questions that motivated the essay.

PG: I remember the Ninth Letter editorial meeting when we discussed your essay. There must have been ten of us in the room, and we were all equally disturbed by and admiring of what your essay accomplished, the emotions you didn’t turn away from in telling your story. We unanimously voted to publish “Crushed,” though many noted that, if a man had written the essay, we would have been having a very different discussion.

MM: Exactly. A man couldn’t have published this essay, even though male teachers also experience crushes on students and from students. But despite high-profile cases like Letourneau’s, the vast majority of adults who engage in predatory behavior with children are male, so readers would rightly feel skeptical of a man’s account. What made writing this easier for me was the moment when my female teaching assistant confessed to also having a crush on the boy. We worked together with the kids every day and trusted each other, so we were able to laugh about the situation and acknowledge that if we heard any of the other instructional teams talking this way, we’d have a fit. It’s comforting, both in reality and on the page, to have another perspective on the sometimes bizarre and taboo and very real emotions of teaching.

It’s great to hear that the decision to publish “Crushed” was unanimous! I appreciated the design of that particular issue, which printed marginal comments on each piece to guide readers through how the editors responded to it. Such a smart choice. Ninth Letter was the only journal I submitted to, and I’m happy that the essay found a home with you all.

PG: Yes, that marginalia! A collaboration between our editorial and design staff. For your essay, the margins included quotes from Van Gogh and the movie Harold and Maude, and little incisive pointers here and there, like the comment “Maxim” for your two sentences, “Complexity is everywhere. Life is complicated, people are complicated, emotions are beyond complicated, worming and turning and transforming, probing and circling back again.” They ably describe “Crushed,” and actually the rest of the essays in Like Love, which, by the way, at the time you mostly hadn’t yet written.

“Crushed” really stuck a nerve when we published it, and even inspired an AWP panel. What was that experience like?

MM: It was really interesting. The poet Heather McNaugher, who teaches at Chatham University, proposed the panel after I read “Crushed” aloud at a Chatham conference. It was called “The Eros of Teaching,” and I was surprised at how well attended it was. During the Q&A, it became clear that many attendees had experienced what I had, albeit with undergraduate students rather than rising seventh-graders, and there’s no outlet for discussing this, not for grad students or adjuncts or tenured faculty. So the panel felt like it created a useful space.

I mean, I don’t want to encourage instructors to be blasé about crushes, and I think it’s worth incorporating discussion of the phenomenon into teacher training. It happens. Better to alert folks to that and equip them to deal with it while also stressing the ethical implications. There’s always a power imbalance between teachers and students, regardless of their ages, and I’m not sure we pay enough attention to that. Teaching is a huge responsibility.

Crushed

There’s a certain way with certain boys, how they walk, a little lop-sided, leaning into one another, how they grimace when their heads go back, laughing to the sky. While their friends wait in the hall, shoes screeching against the tile floor, these boys pack up slowly, smiling under their bangs. They say, “Have a good afternoon,” and “Looking forward to reading Montaigne,” with no sense of irony. Then they hoist their heavy backpacks over one shoulder, give a quick salute, and are gone.

At a certain age—twelve to fourteen, by fifteen it’s over—these boys are dangerous. Outside during morning break, they sidle up, leaning into me the way they lean into each other, sensing how I love being in the middle of them. One in particular, Eli, takes my hand, adjusts my grip on the Frisbee, cheers when my toss reaches the far birch tree. He likes teaching the teacher.

At academic summer camp, where the overachievers go for fun, boys like Eli talk about literature, about the pieces they’re working on, with an earnestness that throbs. In the cafeteria at dinnertime, carrying trays piled with tater tots and chocolate pudding, they ask me to settle a bet. What’s “Hills Like White Elephants” really about? Their eyes drop to the floor, feet shift back and forth. At night they come to me in dreams, and in the morning when I step into the classroom and their heads turn toward me, eyes sleepy, I am shy.

Most of the summer writing students want to be in Fiction Workshop. I teach its prerequisite, Personal Narratives, although I have no idea why this course should come first. We read Virginia Woolf, James Baldwin, Joan Didion and talk about developing a literary consciousness. About what it means to tell the truth. About memory and imagination, craft and technique. “But nothing worth writing about has ever happened to me,” they sometimes whine. “The drama is in the way you think,” I insist, and the dangerous boys nod their heads and grin.

We spend most of each day in a small, carpeted classroom: fifteen students, the teaching assistant, and me. We sit around an enormous seminar table where we discuss readings and do writing exercises. Every other day, three students distribute drafts for the whole class to critique, making the close quarters even more intimate. By the end of the first week, it feels like a month has passed.

In the evenings, during study time, I walk through the girls’ dormitory first. The girls are twelve and thirteen and fourteen, too, but they seem older, less vulnerable. They have breasts and long legs, and some are so beautiful it’s hard to look at them, hard to look away. A few apply make-up expertly and braid their hair into intricate patterns, but I don’t compliment appearances. Instead I say, “I like the way you think. Push that idea further. Bring it up in class tomorrow so we can all learn from you.”

This pleases the girls, but what they really want to talk about is the boys. They want to know if I’ll tell so-and-so that so-and-so likes him, if I’ll relay dares and threats about tomorrow morning’s four-square match. “Nope,” I reply, “no flirting by proxy,” and the girls fall out laughing, squealing until the RA threatens to write them up.

The next dormitory is quieter. Up and down the halls, boys read and write and goof around silently. I make myself at home, sitting on a chair here, a bed there, and taking what they offer—Twizzlers, Cheetos, Coffee Nips. Eli’s roommate received a care package today, and Eli gives of it freely. He just turned twelve, the youngest in the class, and he sits beside me on the narrow bed—elbows on his knees, hands clasped like some kind of professional—and asks about the college students I teach. What are they like, he wants to know, and what am I reading for pleasure? He shows me a wooden duck his grandfather carved and a bracelet he wove during afternoon activities. He opens his laptop to essay number one. “What do you think of this beginning?” he asks, and I’m not kidding, it’s stunning.

The joke at nerd camp is you can tell new instructors by who doesn’t show up to lunch the first day. That’s what happened to me three years ago, after a friend, whose recommendation counted for more than it should have, got me the job. I had no idea how much these kids would know, how eagerly they’d devour lesson plans. I come from the kind of working-class, public-school background few of them share, so it didn’t occur to me that by seventh grade they’d be versed in classical mythology or able to analyze a Van Gogh painting with lightning speed. On that first morning, my class ate through two days’ worth of lessons. I spent lunch hour planning how to get to 3:00.

Now, halfway to a Ph.D. in English and grateful for this recurring summer job, I’m used to adolescents who know more than I do about calculus, molecular biology, the timelines of historic battles. And I’m also used to student writing that might be great for seventh grade but isn’t, on its own, impressive. There’s a slight, perverse pleasure in knowing that in one area, in my area, these kids don’t necessarily excel. So Eli’s opening paragraph takes me by surprise. I haven’t had time to teach him yet.

During the first workshop, we discuss essays about a pet goldfish that died, a baby sibling who arrived like an angel from heaven, and a father who left his family for another man. About the goldfish and the sibling there is much to say. Great descriptions! So relatable! The same thing happened to my fish! I listen for a while, giving the shy students time to participate, and then ask, “What’s this essay really about?” I look around the table, meeting their eyes. “Let’s talk about ideas.” The students gaze back. Some sit up a little straighter. Others twirl pens, snap gum, toy with the colorful bands on their braces. In a moment, ideas start to come, and before long even the author’s conceding that the fish hadn’t meant much to her, even at the time, but the ritualistic burial gave the backyard an aura of the sacred.

When we turn to the third essay, the one about the gay father, silence fills the room. I glance at the clock, prepared to wait a full minute before intervening. At the thirty-second mark, which is much longer at a workshop table than elsewhere, the teaching assistant Tina shifts in her chair and widens her eyes, begging me to intervene. I realize she’s right, that the silence can’t go on so long that the witty, awkward boy who wrote the essay starts to squirm.

But just as I’m about to speak, Eli clears his throat. “OK, well, I thought this was really brave and really moving. I mean, I got a little choked up at the end.” He gives the author a quick smile, then flips through the pages, cocking his head to the side. “But…” Eli’s face tightens with concentration. “I wanted to see more of your father. Especially before he told you he was gay. I wanted to spend time with him so I could feel your sadness when he left.”

The author nods with the heady excitement of being taken seriously, and three new hands go up in the air. Watching these students—children, really, with their oversized tee shirts and budding acne—hold a mature conversation, speaking directly to the bespectacled boy who both loves and resents his father, moves me almost to tears.

In Eli’s room that night I tell him what a great job he did in workshop. He nods and looks at the floor, lips pressed together against a smile. We’re sitting side by side on his bed again, and I have the strong urge to drape my arm across his shoulder, pull him close, touch my lips to the short brown hair above his ear.

During the second week, on a lazy-hot afternoon that’s perfect for a swim, our class fills the narrow computer lab. The lights are off and blinds open, creating the illusion of dim comfort, and the students click along the keyboards with type-A discipline. In the back row, Tina consoles a girl who started to cry while describing her brother’s epilepsy. In the front row, Eli has fallen into a pattern of typing furiously and then deleting with a frustrated shake of his head.

“How’s it going?” I ask, standing to the side so I can’t see his screen.

Eli sighs. “Something’s wrong here, but I don’t know what.” He scoots over and I perch beside him on the chair, our shoulders touching. He’s right. Despite the stunning first paragraph, the essay lacks direction. I say, “It seems like you’re circling around an idea you’re also resisting.”

“Exactly.” Eli rubs a palm along his freckled cheek. His tee-shirt smells faintly of fabric softener, a woven bracelet hangs on his thin wrist. “But what’s the idea?”

I shove him a little with my shoulder. “It’s your essay, you tell me.”

Eli smiles, stares at the screen, wrinkles his brow.

After a moment, I point to a phrase. “OK, what about this girl right here? You say you didn’t like her, but isn’t this whole experience about trying to impress her?”

He leans forward and reads the sentence aloud. “Huh,” he says.

“Could this be an essay about not understanding what you want? About … desire?” I pause, waiting for Eli to blush or fidget the way twelve-year-olds do, but his forefinger goes to his chin, taps lightly, and he starts to grin. Later I show him how to work the prose, using a sentence fragment here, parallel structure there, along with repetition so the music of the phrases carries meaning. “Excellent,” Eli whispers, his mind wrapping around my words. He gets it, and he knows it came from me, and nothing, nothing else I do, is as seductive as this.

Nerd camp is filled with crushes. Kids pair up right and left, a Monday attraction developing and running its course—bad break-up, friendly reconciliation—by Wednesday. And of course there’s a spate of student crushes on adults: girls flock around the handsome math teacher at lunch, boys wrestle in front of the kohl-eyed French TA. Attractions crop up in every class, across age and gender. By the end of the first week, campus is abuzz.

Which makes the middle of week two the perfect time to show the movie Harold and Maude. Every year this choice makes administrators nervous. They worry about the implied sex, the drugs, the suicide, but I argue that the film provokes kids into thinking hard, revising stereotypes, and asking good questions. I don’t care whether students approve of a relationship between a young man and an elderly woman; I want to broaden the assumptions they make about the world.

On the appointed night, Tina and I hold study time in the classroom, pushing tables and chairs against the wall and allowing the students, who bring pillows and blankets, to sprawl on the floor. We dole out popcorn and candy, then sit back and watch everyone squirm. “What?” they gasp in unison when the romance becomes clear. Harold is the age of their older brothers! Maude is like their great-grandmothers! It’s scandalous, nauseating, incomprehensible, or would be if Maude weren’t so vibrant and inspiring. By the end of the film, we’re all a little bit in love with her.

When Tina turns the lights on again, the students blink and shake their heads, then chatter as they pick up wrappers and gather their bedding. One girl jokes that she is no way telling her parents about this one, while a boy insists that even if the gender roles were reversed, it would still be disgusting. Other students counter, insisting that Harold was probably eighteen, what’s the harm? Love is love, they sing, because it’s summer and social hour starts in fifteen minutes on the quad. All’s well, I think, humming to the Cat Stevens soundtrack. Then Eli appears at my elbow, positioning himself so only I can hear and leaning in as if to tell me a secret. “That was a-MAY-zing,” he says, and the look on his face is one I’ve seen before. It’s the look of someone standing in a dark doorway, or sitting in a parked car, someone about to slip a hand around my waist and guide me toward him. For a moment it’s hard to remember where I am, and who this boy is in front of me, with his confidence, his longing. Eli steps back, still looking at me, still smiling, and the intense flush of his cheeks makes my own face burn.

Walking back to the instructors’ dorm, I think about Eli’s perspective. It’s his summer vacation, after all. He’s been looking forward to camp for months, and there’s not a girl out of the hundred here who interests him. The older ones, maybe, the sixteen-year-olds, but he’s so small, so wiry they don’t take him seriously. It’s early August, the days already shortening, and the evening breeze carries the scent of pine, a premonition of autumn woodsmoke rolling down from the mountains. The week after next Eli will be back home again, bored.

And it’s my summer vacation, too. Inhaling that soft, fragrant air, marveling at the silhouetted peaks, the sherbet sky, I feel loneliness settle in my hips. I have friends here, people who teach writing, politics, archaeology, chemistry, and most evenings we get together to eat and drink and laugh about these brainiac kids. Some of us come back year after year. We egg each other on, develop history, have encounters and flings and full-blown affairs, managing the restless energy.

Still, the energy of these certain boys, who think hard and run fast and seem both younger and more mature than they are, affects me. I’m old enough to be Eli’s parent, the person who tells him he can’t go to the mall and has to finish his homework before watching TV. But I’m not his parent. I’m a teacher who spends six hours a day with his class, and not once have I had to reprimand him or tell him to pay attention or remind him to do an assignment. In a group of astonishing kids, he’s the stand-out. Twelve years old, small for his age, smart and sweet and more together than some men I know. Sometimes, when I watch him joking with his friends on the quad, the way they lean into each other, shove each other, laugh and then get serious for a moment, my throat tightens with some emotion I can’t understand. Or maybe it’s a combination of emotions: mournful love, buoyant sorrow, the outline of desire perched between an unknown future and the enigmatic web of the past.

At the end of the second week, Tina and I linger after class. Tina is the opposite of me in every way: tall, blond, graceful, and charmingly on task. She’s the disciplinarian in our room, with a low tolerance for the chaos that often erupts. Today she organizes files of lesson plans on the side table while I select a few essays for her to grade. We’re chatting about the day, recounting funny moments and marveling at how lively workshop discussions have become. The conversation turns to Eli, how insightful he is, how attuned to his classmates. “He’s the opposite of Tom Hanks in Big,” Tina says, “a thirty-year-old man in a little boy’s body.”

We chuckle and fall silent. Then Tina lowers her voice and confesses: “Just between us, and I’m talking serious confidentiality here, OK? I’m crushing hard on Eli.” Tina shakes her head, embarrassed, and wonders whether she’s reverting to adolescence in this atmosphere. I let a moment pass, deciding how to respond, and then give in. “It’s not just you.”

We close the door and laugh ourselves breathless. He’s twelve! And looks ten! We joke that he’ll be legal in six years—how old will we each be then? Tina will be twenty-five, I’ll be thirty-six. She calls dibs.

I point out that if we overheard two male teachers talking this way, the guys next door, for example, who have the fifteen-year-olds, we’d raise the roof. “No kidding,” Tina says with a shudder. “That would not be cool at all.”

That night we hold study time in the computer lab, after which everyone languidly crosses the quad. Tina and I are bringing up the rear, planning tomorrow morning, when Eli jogs back through the dusk. He left his Frisbee in the classroom earlier and really wants it for the morning, can we please, please let him get it? Of course, we say. The three of us head back to the building and when we come outside again, the other kids have hurried into the dorms to get ready for social hour and the quad is empty. Soon this green space will be filled, from ivy-covered wall to ivy-covered wall, with desperately eager teens.

As we walk, Eli talks about a short story we discussed this afternoon. It makes perfect sense to him that Miss Emily slept beside her dead suitor all those years, because she couldn’t bear the loss, the permanence of it, you know? That’s what’s so hard. His voice is earnest, pained, a knife grazing my skin.

Tina glances over, and I shake my head, looking upward as if searching for strength. She laughs and breaks into a jog. “Come on, Eli, school’s out for the day. Throw me that Frisbee!”

He does, and Tina catches it high above her head, then launches it to me. I pause before throwing while Eli and Tina both run backward waving their arms. I aim between them and they sprint, Eli catching the Frisbee half a second before Tina catches him, her long arms wrapping around his waist and lifting him into the air. He howls with laughter as she spins once, twice, then slows down, faces me, and sets him on the ground, her mouth pantomiming a scream and palms rising in a gesture that says, “I didn’t do anything.” For many years this tableau will come back to me: Eli holding the Frisbee and laughing, enjoying our attention, while Tina mocks her own impulse, fingers splayed to assert an innocence that doesn’t quite exist.

Innocence doesn’t exist. Complexity is everywhere. On paper, Personal Narratives is about structuring essays, using active verbs, developing main ideas, but in practice, the only idea I care about is that life is complicated. People are complicated. Emotions are beyond complicated, worming and turning and transforming, probing and circling back again. At the end of three weeks, I want these bright, privileged students to know what they only sensed before: that it’s possible to feel joy and sorrow at once, to be both good and bad, to want and not want at the same time. That the opposite of love is not hate, the opposite of desire is not revulsion. The opposite of every emotion worth having is indifference.

And indifference there is, in week three. All over nerd camp, broken hearts have healed and hardened. “I don’t care,” the students say, walking into the classroom. “He’s lame anyway.” “Whatever.” When Tina and I divide the class into small groups for certain lessons, we strategize about who’s still getting along.

A few students sidestep the drama, among them Eli. Tina and I can’t understand this. How can no one be interested in charming Eli? At breakfast we scan the cafeteria for someone deserving of his affection, and when we head to the classroom I hold my breath for a moment. I keep waiting for Eli to become infatuated with a girl or to discover the attraction of Tina, toward whom several of the boys and most of the girls in our class gravitate at every break. But Eli behaves in week three as he did on day one, smiling with delight when I call the class to order, as if being here, and having me for a teacher, is a prize he didn’t expect to win.

On the penultimate night of camp, when I visit the boys’ dorm during study time, Eli opens his dresser drawer and pulls out a gift. It’s a bracelet woven from purple, red, and green yarns, the pattern more intricate than most. He ties it around my wrist, smiling, then looks me in the eye and with breathtaking gravity says, “The others were practice for this one.”

I pull on my professional face, the one that allows me to speak when emotion balloons inside my ribs, and say, “It’s gorgeous. Thank you.” Then I turn to Eli’s roommate, the boy with the care packages, the athlete over whom some of the girls are bickering. “Okay, slacker, what have you got for me?” I ask, and while both boys fall on their beds laughing, I flee.

After my rounds I go looking for Tina, who is playing pool at a bar in town. When I walk in she’s holding a beer and a cigarette and smiling sheepishly because she’s underage, but I don’t care about that. I raise my wrist and shake it so the bracelet slips along my arm.

“Oh my God!” Tina wails. “I never stood a chance!” We don’t explain what’s so funny, not to the teaching assistants she’s with, not to the math teacher who might come back to my room tonight. Tina and I are role-playing, and also not, and her reaction intensifies the pleasure I feel at being chosen.

And it really is a pleasure. I want Eli to like me best, as ridiculous as that sounds. Because I like everything about him. The way he thinks, the way he smiles, the kindness in his voice when he offers workshop criticism that could come from a graduate student. I like watching the awkward way he walks, taking long steps to keep up with the bigger boys, and the speed of his run, which is somehow faster than everyone else’s. I especially like the way he looks at me at the end of each afternoon, when he hoists that huge backpack over his shoulder and pauses to say, “Thank you for a great day.” Every afternoon he says this, and yes it’s polite, but he means it, too. He is a grateful boy, and I have the sense that, with the merest luck, he will grow into a grateful man. But that future man is not part of my crush. It’s little Eli, here and now, whom I adore.

A crush is about desire, longing, wanting something, but what on earth do I want from a twelve-year-old? Or from any of the dangerous boys I teach each summer? During study hour, as I sit beside Eli on his bed, talking about the arc of a narrative, parallel scenes spin out in my imagination. With his roommate turned away, Eli takes my hand and squeezes it. Or brushes the hair off my face. Or, when I’m feeling particularly daring, our heads bend together over a page, faces turn, and lips lightly brush.

That’s where the fantasy stops. Backtracks. Finds solid ground once again. I don’t want to kiss Eli, not the way adults kiss each other. I don’t even want to kiss him the way kids kiss each other, the way as a kindergartner I wanted to peck Danny Rodriguez’s round cheek. Maybe all I want with Eli is what already exists: the light yet palpable connection that hums between us whenever we’re in the same room. I want that hum, that fleeting, young-boy energy to aim itself, for this brief spell, toward me. Even more, I want to be carried along on its optimism through the rest of this summer and the rest of graduate school and into the unimaginable life that waits beyond. It’s an impossible desire, I know. But the knowing does not make it go away.

Personal Narratives ends just before lunch on Friday. That’s when parents appear, packing dorm rooms and loading minivans and lining up in the hallways for conferences. Tina plays emcee outside our classroom while I admit one set of parents at a time, close the door and tell versions of the same story: She’s a great kid, an excellent writer. He’s a great kid, a terrific writer, but easily distracted. She’s a great kid, a hard worker, and I’m sure her writing will mature over time. The parents are eager and nervous and proud. They have no idea what I know about them.

Eli’s parents come near the end. They’re so young, my goodness, we really are peers, and I can tell immediately—by their sneakers and tee-shirts, their comfortable stances—that they’re not going to ask whether this program will help him get into Harvard. They’re solid, sensible people who just wanted him to do something he loves this summer. The father is tall and wiry, the mother petite. Eli is the perfect mix of their features.

I tell them he’s extraordinary and they nod politely, clearly used to hearing how great their son is. They don’t get it. They have no idea. So I take an extra minute and explain that every last kid on this campus is exceptional, OK? That what I’m saying is not the same as what his middle school teachers have said. I don’t mean he’s a genius. What I mean is that he has something, some mix of sensibility and insight and desire, that sets him apart. Their eyes widen, their faces color. I jot down the name of an online college writing course that can challenge him during the year, and we shake hands. As they turn to leave, Eli’s mother stops and says, “He adores you,” with a tone that seems—am I imagining it?—concerned. So I pull on my professional face and nod. “This was a good class.”

When I open the door to let them out, Eli squeezes in. “You were eavesdropping,” I admonish, ruffling his hair the way adults do to children and regretting it immediately because this is not how things have been between us. There’s a pleading expression on his face, and he speaks quickly at first, then slower, with determination. “I know other people are waiting and I’m sorry, I don’t want to take up your time, but this class has meant the world to me. It really has. And I just want to say, thank you.”

Eli extends his hand toward me, mother and father beaming, and I don’t want this to happen but it does. My eyes begin to fill. Because tomorrow, as I start the two-day drive back to my real life, which does not include unlimited meals and linen service and youthful possibility stretching in every direction, I will miss him. Him, specifically, the most impressive by far of all the dangerous boys.

I blink, shake Eli’s hand, meet his eye for a quick second and step toward the door. “I’ve enjoyed working with you,” I say, and then his mom guides his shoulders, dad right behind, and there isn’t time to catch my breath before the next father fills the doorway.

Heartache is a cliché that is also true, in many situations. My chest feels so tender that I press my left hand against it while extending the right to shake the next man’s hand, and suddenly here he is again. Eli! He worms around the man in the doorway, ducks under the outstretched arms, and before I know what’s happening, he’s crushed against me. His cheek presses to my chest, hair brushes my chin, arms grasp my waist and hold on.

The next father watches. Eli’s parents return. And Eli and I embrace in a way that should stop and doesn’t. And still doesn’t. It occurs to me that Eli is taking control of this story, changing the outcome, moving toward some kind of closure and taking me with him. I know that his feelings this summer aren’t entirely about me: I’m the messenger, the teacher who embodies what he loves about this place where, for the first time in his life, he doesn’t have to hide how smart he is, how much he thinks, how deeply he values literature and art and the capabilities of his own mind. I’m starring in this episode of his coming of age story, just as he’s standing in for all the smart, sweet, not-yet-overbearing boys I love to teach, in my own story of figuring out who to position at the center of my life.

Finally, I let go and take a step back. Eli’s eyes are moist, but he squares his shoulders and gives a satisfied, soldierly nod. “I didn’t want to leave here without doing that,” he says. And how do I feel? Grateful. For his maturity and sweetness. For his courage. And for this moment of genuine, inexplicable connection between a thirty-year-old teacher and a twelve-year-old boy, with his parents looking on.

“Crushed” is from Like Love, published by The Ohio State University Press in September 2020, and originally appeared in Ninth Letter vol. 8, no. 2, Fall/Winter 2011-12.

Michele Morano is the author of two essay collections: Grammar Lessons: Translating a Life in Spain and Like Love, recently long-listed for the PEN America Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay. Her essays and short fiction have appeared in many literary journals and anthologies, including Best American Essays and Wave~Form: Twenty-First-Century Essays by Women. She teaches creative writing and chairs the English Department at DePaul University in Chicago.