Brett Ashley Kaplan

To Be a Writer: Reflections on the Writing of

Nicole Krauss

Nicole Krauss is the author of four striking, award-winning novels, Man Walks into a Room (2002), The History of Love (2005), Great House (2010), and Forest Dark (2017). Her first collection of short stories, To Be A Man, is due out in November (2020). Krauss was a MillerComm visitor to the University of Illinois campus in April 2019, and I had the pleasure of interviewing her on stage at the Spurlock Museum (video and details below).

Krauss’s inventive, subtle writing has earned numerous distinctions such as winning the Orange Prize and the Saroyan Prize for International Literature; her novels have been finalists for the Los Angeles Times Book Award and the National Book Award and to date have been translated into more than 35 languages. Scholars including Victoria Aarons, Alan Berger, Dean Franco, David Hadar, and Jessica Lang, have begun to treat Krauss’s work both on its own and in contrast to other contemporary writers. Krauss’s texts raise questions of memory, trauma, distanciation, scale, and displacement—among other themes. Her novels and short stories consistently experiment with form, often juxtaposing different characters whose life trajectories may resonate with each other but who do not necessarily cross. She often uses first person narration but also third person omniscient and her characters vary in terms of age, gender, and mood.

Her debut novel, Man Walks into a Room, tells the story of Samson, a man whose memory quite suddenly becomes erased (or nearly erased) due to a tumor. As his relationship with his beautiful wife, Anna, unravels—he cannot remember her, after all, he finds his way into the “care” of a doctor whose experiments with memory implants lead Samson to an inheritance of a traumatic memory of a bomb test that he never anticipated nor wanted and which he cannot blot out. While this first novel is not really “Jewish-American fiction” in the way that Krauss’s subsequent three novels and the short story collection most certainly are (Samson is half-Jewish and Jewish histories and stories are present, but barely), I read the importation of the memory of the bomb as an analogy for the Holocaust legacy that many American Jews (and many characters in Jewish-American fiction) hold consciously or subconsciously as part of their psyches. Samson feels the weight of this imported memory and aches to excise it but it refuses to be pulled out and remains, stubbornly, against his will.

When I asked Krauss about this sense of the past ineradicably enfolded into the present and the larger questions of memory—its persistence, our boundedness by the past in her work, she replied: “The question of to what degree we are bound by the past (and to what degree we can become free of it) is one that’s occupied me throughout my career as a writer. In a Man Walks Into a Room, there is definitely this sense in the beginning of the book of this possibility of being freed from nostalgia or the various ways we’re confined to a life and Samson is exploded into this shapeless place of the desert, but it turns out to be alienating, because without memory, we don’t have the ability to empathize with others and if we can’t empathize, then we remain locked in the experience of ourselves. Samson is given the difficult experience, instead, of arriving at empathy through the structures of memory and, the ability to relate to another memory because they just planted it in his mind, which is terrifying. Which is not the way to learn empathy. Underneath all that I was this thinking that this is the unique value of literature—it gives us this opportunity to step into another person’s shoes so vividly and become him or her. You know, when we read a character and we read a really great book that we love and feel for, we become those people and they become us and it adds this whole dimension to our being. That’s an extraordinary thing. And, I don’t think that we can find that experience almost anywhere else. Not in film, not in painting, just in literature. Those questions have always been on my mind from the very beginning.”

Krauss’s next novel, History of Love, is very much about the presence of the past in the present and became her first Jewish-American text. History of Love tells the ultimately interlocking stories of Leo Gursky, a Holocaust survivor and elderly writer who lives in New York in an “apartment full of shit,” and Alma Singer, a kid named after a character in a novel which happens to be called The History of Love, and whose very fabric is sewn from buried memories. Her brother is named after Emanuel Ringelblum who “buried milk cans filled with testimony in the Warsaw Ghetto.” The Holocaust naturally haunts Leo—his entire life unraveled, including his greatest love, due to the displacements of the war. But it also haunts the young girl as she moves through family history and begins to seek solutions to mysteries that have always claimed her. History of Love features many formal innovations including switching between Leo and Alma’s perspectives without a clear path to understanding how the stories will intersect, pages with nothing but “LAUGHING & CRYING & WRITING” written on them, switches between first and third person, and alternative realities presented without resolution. The writing is lyrical and it is easy to see the traces of Krauss’s past as a poet—she began her creative life as a poet and gradually morphed into a prose writer. She explained how she transformed from poetry to prose as if this choice had the sort of accidental quality of what happens to so many of her characters: “My grandparents were all from Europe, and my dad grew up in Israel; my mom grew up in London. My parents met in Israel and then moved to New York, so, I grew up in New York. I knew from the time I was about 14 that I wanted to write, but I thought I wanted to be a poet. For ten years I was very serious about becoming a poet and I went to Stanford and a few weeks into my freshman year, I met an incredible poet called Joseph Brodsky, a Russian poet who won the Nobel Prize. He became a mentor to me. If you had told me then that I was going to become a novelist, a lowly prose writer, I would have been totally shocked. I finished at Stanford and I had a Marshall Scholarship, which brings about 30 or 35 students to graduate school in the UK for two years. I went to Oxford and I was doing a doctorate in English, but I just found that I was at the library every day with all these books of theory and I was too far from my love of literature. I still wanted to be a writer and it seemed absurd to be in the library at the age 21 or 22 with a lot of books of theory. So, I used the second year of funding to get a Masters in Art History at the Courtauld Institute, which is in London, and I studied 17th Century art and wrote about Rembrandt. And then I came back to New York and I was faced with a choice of what to do next. One option was to continue studying – doing a Ph.D. in Art History. Poetry certainly was not going to be any way I could make a living, but it also had become really, really closed down for me, the poems I was writing became smaller and smaller. Joseph Brodsky had encouraged me to write, but somehow this formal verse rather than free verse became really tight and not free. Brodsky had died by that point and I felt like I just needed to break a window in my writing and get some air into it. I had friends who were trying to write novels and I thought, why not, maybe I should try to write a novel. And, so I sat down and I thought of an idea and I took a year and I wrote my first novel, which became Man Walks Into a Room. The moment I was writing that book I felt a wonderful freedom that I still search for as writer and find in writing novels. There’s that freedom because a novel is so ill defined formally, it’s just a long story with a beginning and an end, but otherwise, it’s really an invitation to the writer to try to reinvent the form every time she tries to write one. I found that liberating and I felt at home in the form. That was when I was 25 and I haven’t looked back since.”

Continuing bold, formal innovations and deepening the use of poetic prose, Krauss’s next novel, Great House, counterintuitively features as its main character and as the thread that ties seemingly disparate stories together, a great desk. The wooden desk boasts no less than nineteen drawers, of varying sizes, which one of the narrators understands as signifying a “kind of guiding if mysterious order in my life.” Each of the characters connects to the desk in different ways. It was given to the first narrator, Nadia, by a Chilean poet, Daniel Varsky, who was disappeared as a dissident. Before returning to Chile he had loaned it to the writer who writes seven novels on its mysterious surface before it is given to a child Daniel never knew he had. As was the case in History of Love, the Holocaust is a major force in Great House. Some of the characters are survivors or children of survivors (Krauss is the grandchild of survivors) and the traumatic legacy becomes embedded in the desk itself. Great House also revolves around Israel in ways that will anticipate the major focus on and setting in Israel in Krauss’s most recent novel, Forest Dark. When one of the characters in Great House, Arthur, speculates that the “feeling Jews have when they get off the plane in Israel” is “relief of at last being surrounded on all sides by your own kind—the relief and the horror,” he indicates a split consciousness among some Jews of the interface with Israel.

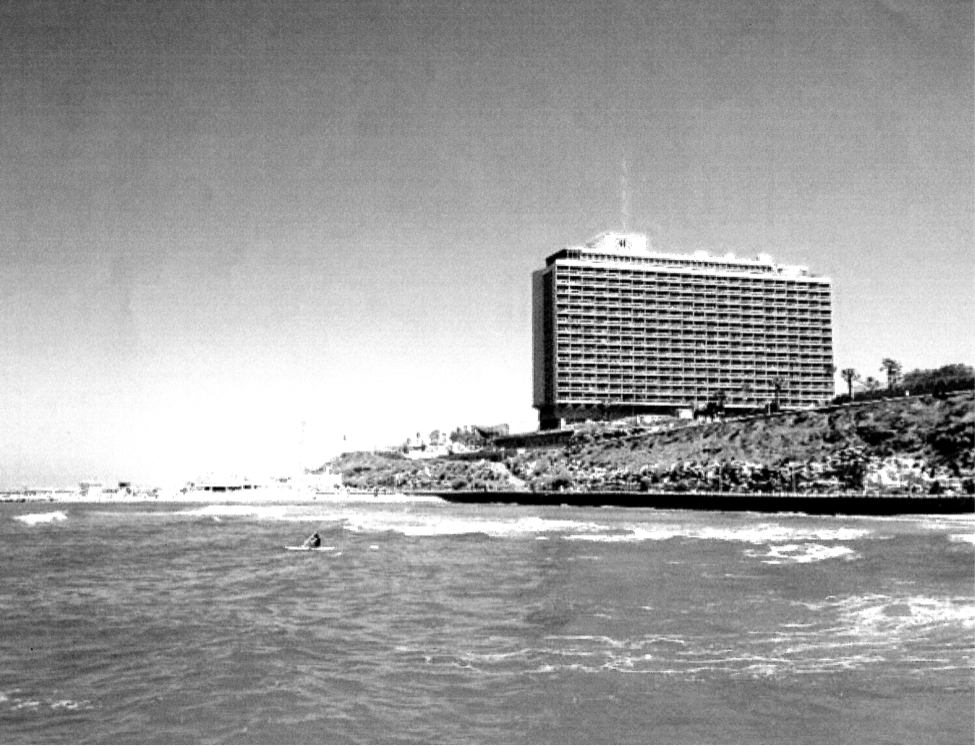

In Forest Dark, the narrative fluctuates between diverse characters who do not necessarily intersect. As was the case with History of Love, the alternation here is also between a young woman (in History she is really a girl) and an elderly man. Forest Dark, as are many other recent Jewish American texts, is set in Israel. These other novels set all or partially in Israel include Jonathan Safran Foer’s Here I Am (2016), Nathan Englander’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank (2012) and Dinner at the Center of the Earth (2017), David Bezmozgis’s The Betrayers (2014), and Joshua Cohen’s Moving Kings (2017). While Israel is a natural topic for Jewish-American fiction and has appeared in classics such as Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint (1969) and Operation Shylock (1993) among others, it is striking that so many recent texts find their characters there. The writer within Krauss’s Forest Dark, who is also called Nicole, turns to Israel and the Tel Aviv Hilton specifically as a place to settle her existential crisis and her feeling of “being in two places at once,” her sense of disaffection and ennui as she gazes out of the window in Brooklyn only to dream of gazing out of the impossible windows of the Tel Aviv Hilton. The Hilton rises above the sea but blocks its views and could be seen as a solid bulwark in stark contrast to the narrator’s failing marriage which she describes as a “sea in which I had begun to sense that every boat I tried to sail would eventually go under.” Escaping this sinking ship, Nicole decamps to Israel only to be sucked into a curious vortex involving Kafka’s unpublished manuscripts, wallowing in a cat-laden house in Tel Aviv. Jewish history and the history of Jewish literature threaten to take over Nicole’s life and being before she re-emerges from the sinking ship to return to Brooklyn. The other major character, Epstein, as we know from the first page, never returns from Israel and is lost in the desert in the guise of King David. Forest Dark opens with these lines: “At the time of his disappearance, Epstein had been living in Tel Aviv for three months.”

Israel also figures as a frequent setting for many of the stories in To Be A Man, sometimes in passing, and at other times in a more sustained way. In “Zusya on the Roof,” for example, Brodman’s daughter “took a break from throwing herself in front of Israeli bulldozers in the West Bank to call home” but then, if he, Brodman, were to answer the phone “she hung up and went back to the Palestinians.” The third person omniscient narrator doesn’t delve into Brodman’s daughter’s commitment to the Palestinian cause—it’s just there. In other stories, especially those, like “The Husband,” set in Israel, the main character, Tamar, rants internally about the “uses and abuses of the Holocaust” and then declaims against the deportations of Sudanese and Filipino kids who had grown up speaking Hebrew and “singing Ha’Tikva.” Taken together, the stories contain a critique of some aspects of Israeli policy towards Palestinians and others. But in this tale, Tamar’s rant floats by and the substance of the story resonates more with the title of the collection: it turns out that here, to be a man means always to be cared for by a woman. “If, having had enough of being a woman, she decides to throw in the towel at last…could Tamar also give herself over to those that would bring her up the stairs to an unknown door, where a woman would be waiting, perhaps a whole family, to take her in with open arms and no questions asked?” As is the case with so many of Krauss’s novels and stories we don’t know the answers.

These stories span roughly the last twenty years with the earliest one, “Future Emergencies,” having been published in Esquire in 2002. Of the ten stories that make up the collection, six were previously published in venues such as The New Yorker, Best American Short Stories, and The New Republic. But there’s an a-chronological logic at work in the arrangement of the tales in the book. The whole book arcs towards the title story, “To Be A Man,” which closes the project. The narrator of this story observes her two teenage sons and sees, finally, that “the thinness is in their genes, the sticks for arms and narrow waist and ribs poking out, all of it written into their bodies like an ancient story, but that sooner or later the time will come when this smallness and thinness will be overwritten, subsumed by mass, and the boys they are now will disappear, buried inside the men they will become.” This sense of becoming, of the ancient story embedded within the current story is a powerful, magnetic force in Krauss’s writing. The archaeological traces of the past seem always to be threatening to become unburied, visible. Israel becomes a literal and metaphorical site of the layers of memory and one character in “End Days” stands atop the “jewel in the crown of biblical archaeology.” But ultimately the title is explained by the brute fact that “To become a man in this country was to become a soldier.”

The narrator of the titular story, a recent divorcée, takes as her lover a man she dubs “the German Boxer.” The narrator admits that she likes “being made to feel physically small next to a man” but then qualifies that with: “Physically small but spiritually powerful. In other words, she liked him to be a wolf in sheep’s clothing until she said he could be a wolf, and then he should be pure wolf with no trace of sheep for the duration of time they should spend fucking in her bed, after which he should go back to being someone who wouldn’t in a million years think of grabbing her throat when he wanted something. Was this a problem?” The narrator is a Jewish woman and the “German Boxer” a man who may or may not have been a Nazi, had he been born some decades earlier. They discuss this stark difference in their traumatic inheritances and ultimately decide that their conversation is “impossible.” The loose thread of this romance never gets tied up and we never know how the story about an impossible to determine alternative past or the story of that love affair gets resolved.

The first story in To Be A Man, “Switzerland,” begins “It’s been thirty years since I saw Soraya,” so we know from the outset there will a long arc, a massing of forgetting and remembering in those intervening thirty years. This story is narrated in the first person but is largely about Soraya, a girl the narrator knew when, as a child, she lived in Switzerland. Soraya disappears, briefly, but when she returns, she’s changed, folded and somehow not herself. “She left it to us to decide for ourselves what had happened to her, and in my mind I saw her in that moment when she’d touched my hair with a sad smile, and believed that what I’d seen had been a kind of grace; the grace that comes of having pushed oneself to the brink, of having confronted some darkness or fear and won.” But we don’t know what happened. Threads are left intentionally loose, flapping in the breeze, and the mystery remains. We don’t know why Tamar’s mother in “The Husband,” accepts this man who claims to be her long lost first husband but can’t possibly be into her home; we don’t know why the narrator in “I am Asleep but My Heart Is Awake” accepts a stranger into her father’s apartment, we don’t know why there are gas masks in “Future Emergencies” (it’s a test, but why? and why were New Yorkers not told it’s a test?), we don’t know what happened to Soraya in “Switzerland,” and we don’t know why or when Sophie and the (male) narrator are in a refugee camp in “Amour.”

Krauss discussed the intentional looseness of her plots in our interview: “I think it has something to do with the fascination with structure and the possibilities that are afforded to us as novelists when we try to reinvent the form of the novel in such a way that suits perfectly the content of that novel. And so, in the case of History of Love, that book just wouldn’t have worked unless Alma and Leo were brought together. In Great House, it wouldn’t have worked had those people been brought together. It would have felt sort of cloying. It really wasn’t the point. In Forest Dark, these characters are not people who don’t relate. Epstein’s life was full of relationships. He has children. Nicole has children. But this is not about that relating, this is about a moment unto themselves. I think that the need to have storylines connect is one with which we can slowly disband. I think that if we allow for richer subterranean connections to begin to speak to us, we can get a much more subtle meaning than if we have to go through all these contortions of bringing a story together. And yet I am obviously trying to create a whole. In these books, I wasn’t interested in short stories. I’m really creating a whole. It’s a bit like the instrumentation of a symphony. I’m very much aware of where harmonies are being formed and where there are echoes and repetitions, and I find meaning in those and I hope that the reader will too. I’m thinking, for example, in Great House of the stone that goes through the window and the stone that is thrown by the SS officers who come to arrest Weisz’s family when he’s in Budapest. There’s that moment where his life is one way and the stone is thrown through the window and his life changes forever. The stone reverberates through the novel and ends up with Arthur and Lotte, of course, when he finds his window broken; it ends up in Israel and it hits Aaron’s windshield when his son is driving. In Forest Dark, there’s a moment towards the end of the book where a taxi driver that is there who drops off Epstein becomes the savior of Nicole in a sense. And so, I like moments when we’re aware that these stories are happening in the same world. But I don’t think that we need things to sort of tie up necessarily on the narrative level.”

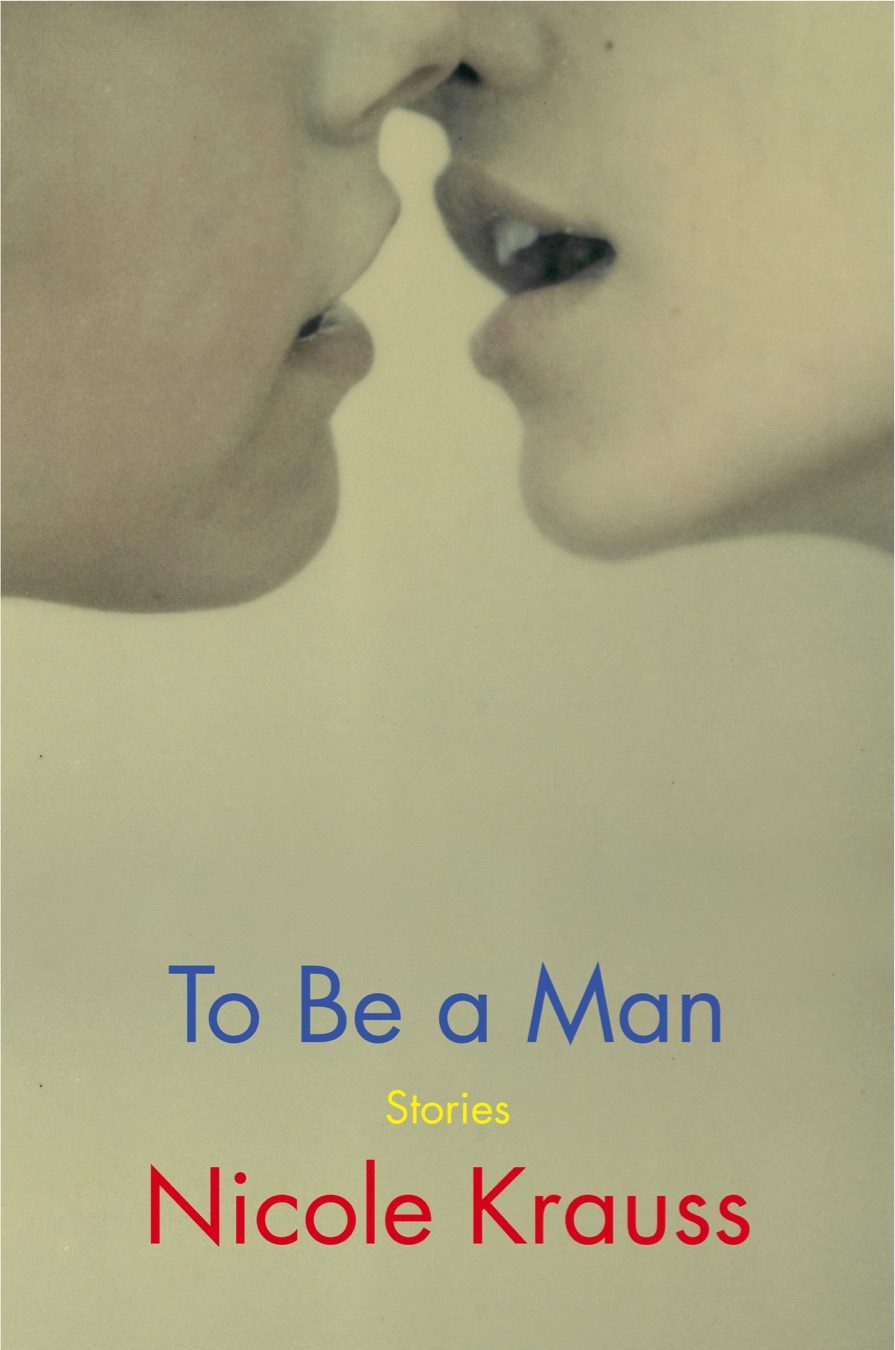

The sense of things untied is very present in the collection of stories—not least because they are disparate tales, not interconnected. The Krauss themes, though, are all there: memory, trauma, mystery, loneliness, separation, longing. The title makes us think the stories will be about gender and the cover photo offers us an ambiguous portrait. Are they two men kissing? A man and a woman? Two gender neutral lovers? It’s hard to tell. There are traces of queerness throughout the collection: one character’s brother is married to and has a child with (via a surrogate) his husband; another character mentions a trans person. But these are just sketched in, suggestions. On closer inspection of the cover, the couple is likely a cisgender man and cisgender woman. But the initial impression, like Krauss’s novels and short stories, remains deliciously ambiguous.

The sense of things untied is very present in the collection of stories—not least because they are disparate tales, not interconnected. The Krauss themes, though, are all there: memory, trauma, mystery, loneliness, separation, longing. The title makes us think the stories will be about gender and the cover photo offers us an ambiguous portrait. Are they two men kissing? A man and a woman? Two gender neutral lovers? It’s hard to tell. There are traces of queerness throughout the collection: one character’s brother is married to and has a child with (via a surrogate) his husband; another character mentions a trans person. But these are just sketched in, suggestions. On closer inspection of the cover, the couple is likely a cisgender man and cisgender woman. But the initial impression, like Krauss’s novels and short stories, remains deliciously ambiguous.

I am so grateful to Deborah Lynch (Greenfield/Lynch Lecture Series), the MillerComm committee and supporters, Dara Goldman and the Program in Jewish Culture & Society, Jodee Stanley and The Creative Writing Program, Antoinette Burton and the IPRH, Lilya Kaganovsky and the Program in Comparative and World Literature, Elizabeth Sutton and The Spurlock Museum, and The University Library for making this event happen. Krauss’s reading and interview are available at mediaspace.illinois.edu.

A longer version of Kaplan’s interview with Nicole Krauss is forthcoming in Contemporary Literature.

Brett Ashley Kaplan directs the Initiative in Holocaust, Genocide, Memory Studies at the University of Illinois. She publishes in Ha’aretz, The Conversation, Asitoughttobe, AJS Perspectives, Contemporary Literature, and Ninth Letter. She is the author of Unwanted Beauty, Landscapes of Holocaust Postmemory, and Jewish Anxiety and the Novels of Philip Roth. She has been interviewed on NPR, the AJS Podcast, and The 21st. She is completing a novel, Rare Stuff. Research for Rare Stuff was conducted at UIUC’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library as well as through many other sources. She is at work on a second novel, Vandervelde Downs, about the recovery of Nazi-looted objects found in a Vietnamese Refugee Center in provincial England. Please see brettashleykaplan.com for more information.

Brett Ashley Kaplan directs the Initiative in Holocaust, Genocide, Memory Studies at the University of Illinois. She publishes in Ha’aretz, The Conversation, Asitoughttobe, AJS Perspectives, Contemporary Literature, and Ninth Letter. She is the author of Unwanted Beauty, Landscapes of Holocaust Postmemory, and Jewish Anxiety and the Novels of Philip Roth. She has been interviewed on NPR, the AJS Podcast, and The 21st. She is completing a novel, Rare Stuff. Research for Rare Stuff was conducted at UIUC’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library as well as through many other sources. She is at work on a second novel, Vandervelde Downs, about the recovery of Nazi-looted objects found in a Vietnamese Refugee Center in provincial England. Please see brettashleykaplan.com for more information.